M-Prize Winner

This story is one of ten winning entries in the Long-Term Capitalism Challenge, the third and final leg of the Harvard Business Review / McKinsey M Prize for Management Innovation.

Story:

Inside-Out Transformation: A Hybrid Business Model for a Converging World

Accenture Development Partnerships is a blueprint for a new business model that changes how we think about the role of business in development and in society. Created by employees for employees, Accenture Development Partnerships is a self-sustaining social enterprise that operates on a not-for-loss basis within Accenture. Here’s how it works: Accenture provides its people and business expertise to international development sector clients free of profit and overhead, employees take a voluntary pay cut, and clients pay fees at a fraction of normal market rates.

At its IPO on 1 January 2001, Accenture was an organization with approximately 75,000 employees globally. Its clients included many of the world’s largest private sector multinationals and developed country governments. The majority of Accenture’s commercial work was in markets in the developed north. It had a limited presence and profile in the developing world. Although Accenture had a newly created Foundation from an IPO endowment and some ad-hoc pro bono activities taking place at local country level, its clients did not at the time include non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or Foundations and only rarely developing country governments.

Eleven years on, the company has grown rapidly to almost four times its size at IPO. It has over 240,000 employees serving clients in more than 120 countries and is capitalized at approximately $40bn. While Accenture’s core focus remains large commercial clients it can now claim all of the top 20 international NGOs as clients. It also works extensively with some of the largest foundations and donors in the world, largely through the work of Accenture Development Partnerships. In addition, the firm’s strategy now includes a clear focus on emerging markets as a critical part of the future growth and prosperity of the company.

Throughout this period, Accenture has remained entrepreneurial, collaborative and non-hierarchical. It has a youthful and energetic culture, with a large number of so-called millennial or “Gen Y” employees, people who are less motivated by the prospect of making a fortune, more by the opportunity to make a difference.

“It has been said something as small as the flutter of a butterfly's wing can ultimately cause a typhoon halfway around the world.” - Chaos Theory

The genesis of Accenture Development Partnerships certainly has elements of Chaos Theory about it. Dating back to my MBA days of 1992, the Friedman-esque doctrine that the sole purpose of business was to maximize profits for shareholders always jarred with me. Was that all there was to it? Was that what I wanted to devote my career to?

This wasn’t an early mid life crisis. I was happy in my role, happy at Accenture and doing fine financially. But my career was to about to make a significant course correction. More than 13 years on, it’s strange thinking back to the simple, ordinary event that caused this change.

It was a very normal day in March 1999. I was on an unremarkable trip to work at a client site, travelling on the rather clunky District Line of the London Underground. I wasn’t expecting anything out of the ordinary to happen. The “trigger” was the Financial Times article I read that day about Voluntary Service Overseas’ (VSO’s) new corporate volunteering program called “VSO Business Partnerships”. Instead of seeking cash from business (still the norm to this day), VSO wanted business skills. There was no shortage of doctors, nurses and teachers applying to do a two-year VSO placement - but there were very few accountants, MBAs and business managers. VSO wanted companies to supply them with people with these skills for about 6-12 months at a time, on a loan basis, with their jobs held open for their return.

This short article had a profound impact on me. A switch seemed to go off in my head. Might this be the “missing link” in my quest to understand the broader role of business in society –a wake-up call in terms of how I could apply my own expertise in a different context for a different impact?

To their credit and thanks largely to the support of one senior Partner, Willie Jamieson, Accenture agreed to a pilot allowing a number of volunteers to take part in the VSO program. Within a year, I found myself exchanging the gilt-edged lifestyle of business class flights, expensive hotels and fancy restaurants, for a basic apartment in a small town called Gostivar in western Macedonia. Despite being at the heart of Europe, Macedonia was ravaged by poverty, high unemployment and ethnic tension. It was suffering from the aftermath of the war in Kosovo and had its own civil war brewing.

I worked in a small business support center for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) seeking to build the business skills of local staff. Despite being on a 95% salary reduction, I had never been more motivated in my life! The business context was radically different–I’d been living and working in a cocoon–this was a different world. I questioned my role and the impact I was or wasn’t having on issues that were complex and systemic. How much more could I get done if I had my normal team of consultants working with me? Why were organizations such as Accenture conspicuous by their absence in the developing world? Why is the provision of international business expertise left to contractors and day rate consultants?

Surely Accenture could and should do more than allow a few well-meaning volunteers to have sabbaticals in the developing world? Could we go beyond the industry-default pro bono model which produces piecemeal services and creates good stories in annual reports but often doesn’t add up to much in terms of scalable impact? Could we create a non-profit business within a for-profit business? Could we fly in the face of conventional market wisdom which says you must pay premium wages to attract and retain premium skills? I’d been working as a volunteer on a local stipend, but surely others would take a voluntary salary reduction too? Lastly, and most significantly, would Accenture give up profit in lieu of other tangible business benefits?

On the way home from Macedonia, I tasked myself with putting this thinking into a form my colleagues at Accenture couldn’t ignore. Instead of producing a thick deck of PowerPoint slides, I wrote a faux press article projecting six months into the future. It was set at the World Economic Forum in Davos where Accenture’s Chairman had just announced the launch of an innovative new not-for-profit to great acclaim. This faux article got the attention of the Chairman who agreed to discuss it over breakfast. He wanted to hear more about the idea. The journey to create Accenture Development Partnerships had begun.

Assembling a Guerrilla Movement

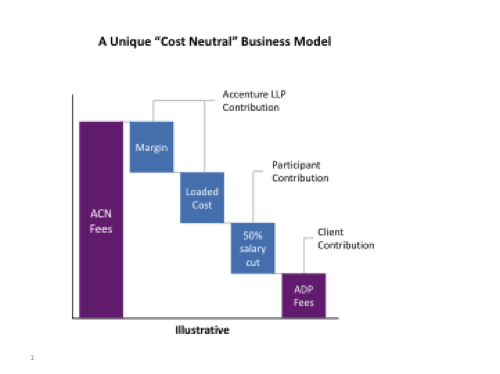

We had a mandate to do more. First step: put some flesh on the bones of the idea to create a new hybrid business that would effectively turn the classical management consultancy model upside down. A business model that was based around a three-way contribution: Accenture provides access to its high performers free of profit and corporate overhead; these employees voluntarily give up a substantial percentage of their salary; and non-profits would cut a check to Accenture for consulting and technology services at significantly reduced rates, with no reduction in quality for those services. The diagram below illustrates these three contributions from Accenture (ACN in the diagram), employee participants and clients.

This is where the concept went from an individual dream, to a pioneering team; it’s where “I” became “we” in the evolution of the story. At this stage we were a “guerilla movement”–a small group of supportive friends and colleagues who worked in their spare time, evenings, weekends, coffee breaks, whenever. We set out to gather data on the latent needs of the development sector, what our competition were or weren’t doing, sizing the market opportunity, and so on. Jointly, we took our findings to Accenture’s UK leadership team, seeking their buy in. Our ask? We wanted each unit head to lend us a body to be part of a feasibility study.

Naturally we targeted supportive leaders first–the ones who “got it”--or the leaders we knew best. Thankfully, most said yes and by the time we got to what we thought would be the tougher nuts to crack, our sales pitch had sunk to “all your peers are contributing, you don’t really want to be the odd one out do you?”

Feasibility Study and Pilot Phase (2002-2003)

January 2002: a new year and an exciting new dawn for Accenture Development Partnerships. At last we had a team of full time resources for three months dedicated to bringing the vision to reality.

We had three questions to answer:

- Would organizations in the international development sector buy Accenture services if the price was a fraction of normal market rates?

- Would the numbers add up to make the model sustainable?

- Would enough employees be willing to work on the other side of the world on a much lower salary?

We had three work streams, each comprised of two people, to answer these questions. From extensive interviews with non-profit leaders, it became clear that there was a genuine interest and need for our services. The finance team showed that if overhead and profit were waived by the firm we could take very significant costs out of the business model. Yes, the numbers could add up!

But perhaps the most significant finding came from a survey of thousands of our staff. We not only asked about their interest levels but also how well they were rated within Accenture. The results showed a strong correlation between interest and performance--the bell curves were skewed to the right, meaning that the people we wanted to attract, retain and develop in the business were exactly the people to whom the proposition most appealed.

This certainly captured the attention of leadership and the feasibility study soon morphed into a pilot. It began in the middle of 2002 with a handful of staff willing to walk the talk on the salary cut, and just three small projects: One was with CARE International (one of the world’s leading humanitarian and development aid agencies) in Vietnam developing a country strategy; one with the International Finance Corporation (a World Bank Group that promotes sustainable private sector investment in developing countries) in the Balkans looking at small and medium enterprise development; and one with the UK Government’s aid agency on the use of technology in humanitarian response.

The pilot was a powerful demonstration of employee interest. It also confirmed our hypothesis that non-profits were prepared to pay for our services if the price were right. We were ready to formally launch Accenture Development Partnerships in 2003.

Accenture Development Partnerships 1.0 – The Early Years (2003-2008)

The first iteration of Accenture Development Partnerships was very much focused on working with NGOs – non-profits that would never normally have access to such services. Of course, we couldn’t dream of telling these international development experts how to do their work better–we couldn’t tell Oxfam much about education policy, the World Wildlife Fund about the environment or UNICEF about maternal health. But we could tell UNICEF how supply chain expertise could improve the last mile logistics of medicines and vaccines, and we could tell Oxfam about the role that systems, processes and technology could play in improving its back office functions. We could also help the sector as a whole with strategy, change management, knowledge management and the design of new operating models to allow them to grow in the future.

But we weren’t confined to the back office—we also focused on bringing innovation to field programs. How could new business thinking and new technologies offer innovative solutions to the old problems of development? Could we train nurses more quickly on an eLearning platform than in a traditional classroom environment? Could the mobile phone be used to track the spread of diseases, or as the bank account for the un-banked in Africa?

Even good old traditional project and program management–taken for granted as part of the DNA of Accenture–could be highly valuable in ensuring that complex development projects were delivered on time, results monitored and evaluated effectively, and critical dependencies planned for.

The rise of the hybrid career

The reaction of employee participants was quite incredible. Conventional wisdom dictates that you get the best education possible and then face a binary choice when leaving university: either you join a public or “Third” sector organization and do good, or you join a business and do well. If it’s the latter, one makes a great deal of money and then as retirement looms, the desire to “give back” kicks in – the philanthropy gene comes to the fore and large amounts of hard earned cash gets donated to so-called good causes. Sound familiar?

But what if you don’t want to wait until you’re 60 to do good? What if you feel you have the most to give in your 20s or 30s? We started thinking in terms of a “hybrid career” that blends all the attractive benefits of training and remuneration found in the private sector with opportunities to apply core skills to social challenges.

This had enormous and immediate appeal for our people:

“The role offered me a unique opportunity to apply my business skills in a challenging sector, gain international experience, and take ownership of a project that will directly benefit those less fortunate.”

Andy Fox of Accenture’s Chicago office assisted the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), the world’s largest humanitarian organization, with the development and implementation roadmap for its federation-wide Resource Mobilisation strategy.

This didn’t have to be a one off. We had employees who would do one, two, three or even more projects. They’d go back into the business in between and often get promoted. Of course, others didn’t want to go back at all. But most felt they’d found a balance that would allow them to do good and do well at the same time.

The wide variety of projects, clients and countries we operate in makes it something of a challenge to manage employee expectations. Some want a truly grass roots experience, working in an African village with HIV/AIDS orphans or have very vivid images of humanitarian relief from a post Haiti Earthquake fundraising video, designed to pull on the heart strings (not to mention the purse strings!). We do have projects that offer just that–we’ve done a strategy for a local NGO in Kenya that supports HIV/AIDS orphans and we’ve been heavily involved in the reconstruction of Haiti through the likes of NetHope’s innovative ICT Academies. But mud huts and broken buildings are not our normal working environment – offices in the capital cities of many developing countries have nice desks, pot plants and WIFI access which can come as a surprise to many!

The size of teams can vary too. We try to avoid single person projects where possible–it doesn’t allow us to bring the right blend of capabilities to clients and also doesn’t make for the most enjoyable employee experience. Team size can vary from just two people on their own in a particular country up to six to eight people working on a larger program. In some countries, such as Kenya or Tanzania, we will have multiple teams working on different projects with different clients but in the same city. In Nairobi, for example, we’ve got something of a mini community that works hard during the week and then socializes or explores the country together on a weekend.

While projects do differ quite radically, there are common elements to the employee experience. We refer to these as the “three Rs”: Release, Reintegration and Recognition.

- Release: Individuals who satisfy our performance criteria (you must be in the upper bands) can apply to do an Accenture Development Partnerships project and then seek approvals from HR and the entity in Accenture they are deployed to. Once a project has been found that matches their skills and availability (and personal preferences as much as possible), they attend two days of training which most love.

- Reintegration and Recognition: These two go hand in hand--something we perhaps didn’t pay enough attention to in the early days. Employees will have had an exciting, demanding and sometimes life changing experience which will have tested their resourcefulness to the limit. They will usually come back better, happier and more engaged (see graph below of participants’ scores versus the wider firm). However, some will struggle to adjust to coming back to a “day job” where they may have less responsibility or client exposure. Some of this is inevitable but we’ve worked very hard to mitigate these downsides. Recognizing the contribution of the individual through the formal performance management process, as well as informally in the likes of community meetings, goes a long way to making the returning participant feel valued. We also seek to ensure that the new skills, development knowledge and confidence can be harnessed back in the commercial business, often on commercial project which have elements of sustainability or emerging markets to them.

However, what makes my job really special is hearing the stories of participants–like those of the teams who helped reconstruct Banda Aceh after the tsunami or helped transform a child sponsorship charity’s processes from paper to digital. We even had our first marriage of a couple who met while on a project with the United Nations in the Eastern Cape of South Africa!

Accenture Development Partnerships 2.0 – An Inflexion Point (2009-2011)

After a period of rapid growth, the business had by 2009 reached something of a plateau. We were at an inflexion point and the team thought hard about how to take Accenture Development Partnerships to the next level.

Accenture Development Partnerships’ Growth (2003-2010)

The outside world had not stood still. Accenture Development Partnerships found itself at an interesting nexus:

- Accenture’s private sector clients were engaging in development beyond philanthropy

- NGOs were starting to view business as a potential part of the solution as opposed to just being part of the problem

- Donors and governments were experimenting with new forms of financing or “impact investing” to catalyze these new forms of collaboration.

We had many years of experience working in both the engine rooms and the board rooms of non-profits, so we understood development well and the role that business thinking and business capabilities were increasingly playing. But we’d identified a trend which was to have a profound impact on our strategy. The trend has become known as cross-sector Convergence - where business, government and civil society are converging to create markets and innovative solutions that tackle development challenges. Cross-sector convergence goes beyond the current discussions around shared valued and inclusive business models to talk about a more profound change that will challenge the roles, structures and actors within the broader development landscape. More about this can be found in our report entitled Convergence Economy: Re-thinking International Development in a Converging World.

The opportunity to have a more systemic impact was clear. While we would continue to provide business and technology advice to NGOs and foundations and support their programs in the field, the most exciting and innovative work started to emerge as commercial clients leveraged Accenture’s convening power to act as a broker, or more often an integrator, for a new breed of partnerships and increasingly complex coalitions. This meant we could, for example, work at the interface between Unilever and Oxfam to get more smallholder farmers in Tanzania into the corporate value chain; and with Barclays, CARE and Plan to take the bank’s micro-finance offerings to village level where their NGO partners had the reach, the trust of the community, and an understanding of local needs. We even worked with Cisco, Intel, Microsoft and the Ministry of Education in Tanzania to pilot new ways of creating virtual classrooms to address failing infrastructure and a chronic shortage of teachers in the country. For more on this, watch the Tanzania Beyond Tomorrow video here.

We were having more impact. We had more visibility. And we had more potential to really address the complex and systemic challenges of development.

What’s more, this type of work added a new dimension to the original business case. Cross-sector convergence work meant that we could expand and enhance our relationship with some of Accenture’s most important clients globally. Not only could Accenture continue to work commercially in its value chains on a for profit basis, but we could also use Accenture Development Partnerships to work in its broader business ecosystems, for our clients’ clients, on issues that were strategically important to their business but also were about enhancing development impact.

This saw us work increasingly side by side with Accenture’s Sustainability Services group, which led to commercial pull through--i.e., we won work that we wouldn’t have on the back of Accenture Development Partnerships. Similarly, we were able to go deeper in terms of execution of projects than a normal commercial for-profit model allows.

Becoming Part of the Fabric of the Firm (2012 onwards)

The last ten years have been a fabulous and rewarding roller-coaster journey of discovery. The next ten years have the potential to be even more exciting and more importantly, impactful.

The self sustaining and scalable business model of Accenture Development Partnerships means that we will continue to grow, I expect exponentially. I’d like to think that our so-called “cost neutral” business model can be a blueprint for others to follow. After all, if businesses are comfortable with the notion of having profit centers to drive growth and cost centers to enable that growth, surely it’s not impossible to envision cost-neutral centers are part of that business ecosystem; hybrid delivery models that may drive a broad range of benefits such as innovation, market intelligence, employee engagement and many more – just not pure dollar profit! Can the notion of the “Corporate Social Enterprise” become part of the standard business vernacular. What role can we play to help companies identify, nurture and scale the latent socially minded innovators or “intrapreneurs” in their midst?

In terms of our own mission, I see this expanding to unlock even greater synergies with our commercial business. For example, we will soon be taking on employees from our clients to gave them the same leadership development experience we offer to our own people. But beyond that I’d like to see us become almost a conglomerate of social enterprises housed under the corporate umbrella of the Accenture brand. We’ve built the engine for transferring skills and knowledge at scale to the development sector – could that capability now be augmented by in-house capital to co-invest in new ventures with our for profit and non-profit clients?

The end goal is become part of the fabric of the firm – a small and very distinct part perhaps, but one that has an impact and influence directly on Accenture and indirectly on its clients. Yes, I believe tails sometimes can wag dogs. But only time will tell for sure.

Building Resistance to the Corporate Immune System

When it came to HR issues, legal and commercial reviews, financial control–in fact, almost any internal function, we often found ourselves somewhat perpendicular to policy. The internal rules and controls that were designed to ensure the company could be successful at scale in developed markets working for large commercial clients were often wholly unfit for working on small projects in emerging markets for non-profits.

As a consequence, we had to negotiate “policy-lite” work-arounds for Accenture Development Partnerships projects. We would never want to cut corners on procedures related to employee safety for example, or the quality assurance of deliverables. But equally, the rules designed for $5 million contracts could not be blindly applied to a project worth $50,000.

One of the best examples of the need for policy workarounds is in HR. Rates of growth within Accenture Development Partnerships are somewhat inverse-cyclical--i.e., when the business is booming, getting high performing employees released to work on non profit generating projects can be challenging. Conversely, during economic downturns, there’s a surplus supply of people and the business is delighted to offer us more folks. The challenge is that a downturn is often accompanied by a headcount freeze in HR – just as we need more to keep up with rising demand. Having the Global HR Director on our internal Board tends to help when such issues get escalated.

Changing Paradigms in our Clients

The reactions of this new breed of non-profit client were mixed. Looking back, I was naïve. I thought that if we could offer Accenture’s expertise at a fraction of market rates then the queues would be out the door. Not the case! Latent inertia and mutual distrust between the sectors emerged. The stereotypical and deeply entrenched view was that large businesses donate money to charities; that charities don’t give money to corporates. I’d try connecting with the COO or CIO and they’d want to redirect my call to fundraising… “You’re from Accenture? Send the check to them thanks”. I explained that we didn’t have a check to give – it was skills we had to offer - that I’d rather hoped that the check would come from them to us. Somewhat unsurprisingly, that often brought the conversation to an abrupt end! It’s very difficult to persuade someone to pay for something they’ve been used to getting for free. I’d often reframe the discussion from payment at a discount to co-investment. Accenture is investing, our employees are investing and we expect you to invest too.Thankfully, some pioneers took a leap of faith. Despite our lack of track record in the early days, they could see the value. Word of mouth spread and soon they started to call us (and thankfully still do).

A Split Reaction from Leadership

The reactions of leadership were as mixed. I hold the view that senior executives tend to split into three even bodies of opinion on most topics: one third will be positive, one third neutral and one third negative. Accenture was no different. Many wholeheartedly embraced the idea--really got it. They wanted to support teams in their spare time, and talked effusively about the uplift in skills and engagement they’d seen in past participants. Another third were more neutral, often passively positive “it seems like a good idea, of course we should do it”--unless of course that meant releasing one of their top performers on a non-profit project for six months--that was different. And the last third were more hostile. But there’s nothing quite like peer to peer influence as a tool to win over the hard liners.

I sought to use senior executives who were heavily engaged in providing quality assurance to projects, to get other colleagues involved, or to lobby local leadership on our behalf. Perhaps the most impactful use of this tactic was by a senior executive called Stephen Zatland in the UK Practice, who had been an active voluntary supporter for many years. When he took on the responsibility of developing the training curriculum for senior executives, it provided the perfect platform to communicate to this critical audience. Three times each year Accenture brings together around 500 senior leaders for a week-long intensive training course at the massive St Charles campus near Chicago. The highlight of the week is a keynote speech on the final day where world leaders such as General Colin Powell, President Gorbachev and F W De Klerk have spoken. To his great credit, Stephen has given me a 20 min slot as the “warm up act” for the main event. Invariably the room is packed and it’s the rare occasion when blackberries are switched off! These sessions have been invaluable for changing perceptions in the broader leadership and are worth more than 1000 internal emails in terms of explaining exactly what we do and why.

Intended Benefits

In terms of direct benefits, the first generation business case was very much around recruitment, retention and skills development. It became clear that many people were staying with the firm largely for the opportunity to do an Accenture Development Partnerships project. Or had done an Accenture Development Partnerships project and came back more engaged and more inspired. Attrition levels for those returning from Accenture Development Partnerships assignments were 2% less than the company average.

To develop differentiated recruitment messages, we developed an internship program that was targeted at attracting the crème de la crème in business schools and universities across the world. We’d offer an internship with a difference. Instead of a summer spent working in London or New York with a commercial client, they’d be living on the ground in Kenya or Indonesia with a non-profit client.

Carmel Schindelhaim, a biochemistry student at Stanford, stepped out of the lab and into the world of business consulting when she took up an internship with Accenture Development Partnerships.

Working with the Tanzania Cotton Board and the Tanzania Gatsby Foundation to help build PAMBAnet—an information management system to support the implementation of a Contract Farming model in Tanzania’s Cotton sector-–she found a number of parallels between the world of science and business.

Says Carmel: “This six-week internship offered the ideal opportunity to explore my long standing interests in business, technology, and especially international development. As someone who enjoys a challenge, I was certainly satisfied—the experience has allowed me to refine my critical thinking skills and consider the bigger picture. I have acquired new technical skills, identified hidden strengths and improved my communication and team work capabilities … and had an incredible adventure. I would without hesitation recommend an internship with Accenture Development Partnerships.”

We weren’t doing this because we needed resources. We were doing this to show a different side of the firm. And it worked. We attracted people who perhaps hadn’t considered consulting or indeed Accenture in the past. Many of these recruits became star performers in their own right when they joined the firm. One, Kimberly Hurd, won consultant of the year in 2009!

Unintended Benefits

We’ve always seen the leadership development benefits as being an important benefit. The leaders of tomorrow, whether in Accenture or any other successful global business, will not only have experience working internationally, they will be comfortable working cross-culturally, cross sectorally and in a business environment that is a lot more challenging than their own home environment. Accenture is essentially a human capital business and Accenture Development Partnerships is a proven incubator of talent. We may send our best people but time and again they come back even better--more engaged, more confident and more competent. They come back having had challenging and testing experiences and with new insights that can be often be applied back at their normal client environment. For example, I’ll never forget watching a relatively junior consultant confidently present to the President of Tanzania when he made a surprise visit to check on progress of the education program we were working on. Experience of interacting with C-suite executives is important to any consultancy – but this was “P-Suite” experience!

Spending time in another culture has been an opportunity for personal development, and a chance to witness the technology world from another angle. Professionally, the breadth of my responsibilities has provided the biggest growth opportunity. On a typical Accenture Technology engagement you are part of a large team and do not have this breadth to address on a single day.” - Mickey Kavanagh, Accenture Development Partnerships project manager, Financial Sector Deepening (FSD) project, Kenya

But beyond the people benefits and the fact that we were gradually building intelligence on the next generation of emerging markets, our new strategic focus on cross sector convergence offered us the chance to extend and enhance our relationships with traditional commercial clients. The partnerships we were involved in--linking businesses with other businesses and with NGOs and development agencies--may tend to be small in monetary terms but they have a profile with the senior leaders of our clients that is disproportionate to their size. Accenture Development Partnerships is opening doors that are otherwise closed, providing our senior executives with the content to have a different and engaging conversation with their clients.

“We believe your contribution will be extremely valuable, not only because Accenture is a worldwide reference in management consulting but also because of Accenture’s presence in the social development sector, through Accenture Development Partnership (ADP).” – Vale Foundation

Care Bangladesh – Rural Sales Program

Employment opportunities for women living in rural Bangladesh areas are limited and these rural communities often don’t have easy access to basic personal hygiene and nutritional food products. At the same time, these communities represent a growing, untapped market for retailers selling these essential products.

To help address these issues, CARE and Danone Communities got together with Accenture Development Partnerships to help transform CARE’s established rural sales program into a more innovative, commercially viable social business to help create employment for thousands of rural women as well as offer new market entry opportunities to private sector partners.

How we helped

The objective was to rapidly upscale the current operations of 80 distribution hubs to 400 hubs, thereby helping increase the number of rural sales ladies six-fold and creating meaningful employment for 12,000 women. We helped to:

- Design and implement an operating model that would help support rapid expansion

- Design the governance structures to help support the alliance model

- Define the supply-chain, performance monitoring and financing capabilities to assist rapid growth

The results

This innovative cross-sector alliance has successfully demonstrated the power of multi-stakeholder collaboration in the effort to achieve high impact development outcomes with shared value. Private sector partners have been able to expand market coverage into otherwise unchartered rural areas whilst at the same time providing the rural poor with important income generating opportunities and advancing important development outcomes such as gender equality and sustainable livelihood creation.

Importantly, the project also offers a highly scalable and replicable template for future social enterprises.

Lastly, let me share a more lighter hearted view of my own personal performance metrics. The table below is a copy of a relatively recent monthly Senior Executive scorecard which I still receive. You could be forgiven for wondering how anyone could consistently score straight zeros and still keep their job! The strange acronyms for the different measures are not important - they primarily relate to profitability, commercial sales, growth etc. My main point in sharing this is that if we aspire to innovate in management thinking and processes, then we must also seek to innovate in terms of the way performance is measured and rewarded inside corporations.

Lesson 1: Pick the A-Team, but don’t recruit in your own likeness:

One of my biggest learnings is the fact that to be successful you need to be surrounded by a great team of people. I'm lucky that I really have the “A Team” in Accenture. The context we work in seems to act as a lightning rod for talent and I couldn't handpick a better and more capable team of people than the ones I have to work with now. It's important to take people who are good at the things you are not good at, or interested in the things that you're less interested in. Diversity in my mind is what makes great teams

Lesson 2: Bottom-up push needs top-down pull

I learned very quickly that if I wanted to try to drive change from the bottom up, I’d need to have support top down from leadership. I think that applies to change in any organization, however big or small.

The role of leadership evolved over time. In the early days we needed air cover–we had to ensure that the idea would not be snuffed out by someone blindly following inappropriate policy or procedure. But over time I realized that the rules had to change: this idea would actually need oxygen if it was to avoid withering on the vine. In the beginning it was the Chairman, Sir Vernon Ellis, who provided the air cover and protection. When he retired, he made sure that a new ermerging senior leader (Mark Foster, former Group Chief Executive of Global Markets and Management Consulting) would take over. We were lucky that this leadership transition was handled smoothly. We’re now onto our third executive sponsor, Sander van’t Noordende, Group Chief Executive of Accenture Management Consulting, replaced Mark in 2011 and is thankfully proving to be every bit as supportive.

Lesson 3: Don’t change companies, change the company you’re in

If you’re seeking a new challenge or if you want to have more social impact and meaning from your job, don't change companies, change the company you’re in. Many people reach a stage in their careers or jobs where they’re looking for a bit more meaning from their work. They want to do something different or are frustrated with the role they’re in. I would argue that rather than going down the normal route of sharpening the resume and simply changing jobs, the potentially more impactful option would be to change the company—or sector--in which you are working.

That may sound a bit glib and I’m not overinflating the amount of change we’ve had in Accenture, but small positive change in large organizations equals impact. People are often most effective at doing that when they’ve been in a company for a few years. Who else knows the key people as well as you do? You’ve developed an internal network and know how to cut corners on policy and often who the right people are to get things done. Often these people are not the most senior. Social Intrapreneurs will be most effective when they’ve got these qualities--and they can’t be developed overnight in a new company. Experienced employees should think carefully before needlessly squandering that potential for change.

Lesson 4: Be Pleasantly Persistent

Many years ago (when I had a “normal” job), a client told me that I was “pleasantly persistent”. At the time, I saw this as being shorthand for “pain in the backside”, which no doubt I can often be. But the learning for me was really around the need for resilience. Striving for change and battling corporate inertia can be very tiring and it’s very tempting to give up hope. Numerous barriers, obstacles and small-minded thinking can get in your way. A degree of unrelenting optimism and resilience is required. The prize is too great to give up easily!

I have tried to make the point throughout that Accenture Development Partnerships is not (and never really was) a one person effort. There have been a huge number of people – far too many to mention - who have played a critical role in helping us get to where we are today.

I would single out a few of my colleagues on our Leadership Team who have loyally committed their careers to our common vision: They include Dan Baker, Roger Ford, Louise James, Chris Jurgens, Jessica Long and Angela Werrett

Also, the supportive leaders in Accenture who believed in us and offered support and guidance for many years: Sir Vernon Ellis, Mark Foster, Mark Spelman and Sander van’t Noordende

Jill Huntley (for her work at the set up stage)

Lastly, Mark Goldring, former CEO of VSO (and now CEO of Mencap) who has been a coach, mentor and friend since the beginning

Accenture Development Partnerships Introduction Video

You cannot focus on the same business model if the industry of the business and the technology is changing. You need to have a hybrid business model to cope up with the trend and to easily have a solution to upcoming problems in your business.

Regards,

Maryann Farrugia, Visit My Crunchbase Business Profile:

https://www.crunchbase.com/person/maryann-farrugia

- Log in to post comments

Making a practical difference to real lives in really tough situations and building lasting cultural and capability change in the people and organisations you touch with your pleasant persistence. Properly inspirational for all of us. And so relevant to today. Thank you.

- Log in to post comments

A great read and really something that all big companies can learn from.

- Log in to post comments

I have been following this innovative project with an interested eye since reading an article outlining Gib's trip to Macedonia over a decade ago. It just goes to show that it is possible to bring about real change on a global scale by being (among a load of other things) “pleasantly persistent”.

- Log in to post comments

I have been following this innovative project with an interested eye since reading an article outlining Gib's trip to Macedonia over a decade ago. It just goes to show that it is possible to bring about real change on a global scale by being (among a load of other things) “pleasantly persistent”.

- Log in to post comments

I think this is a great program, and I look forward to one day participating in it. Good work Gib.

- Log in to post comments

Having recently relatively joined Accenture it was great to read the history of ADP and the great work that Gib and the team have been doing. I'm in the "get it and love it" category.

- Log in to post comments

Truly inspirational stuff! A blueprint in hybrid careers for much of the corporate world!

- Log in to post comments

You need to register in order to submit a comment.