Story:

Changing government one employee, one citizen, at a time

Citizen engagement and participation in collaborative decision-making in government are to be highly valued and pursued in a democracy. There are some basic principles that are core to successful citizen engagement.

These same principles can be applied within government organizations to radically change the stubbornly bureaucratic, command-and-control workplace. By doing so, the individuals who comprise the government work force will be more able to engage and collaborate with citizens because they will be practiced in those skills.

There is not an end to this story, only a beginning.

The characters include citizens with an interest in public lands, perhaps for recreation, perhaps for the remnants preserved there that tell the long-rooted history of the place, perhaps because they care about the wild things. There are also government employees – both in the field offices and in central offices -- who also care about the land. There are other characters as well, not as visible, who research and publish the studies about the land, about how to manage the land, and about how to manage the people who are managing the land.

The setting is U. S. federal land-managing agencies, which have the responsibility of caring for public lands and the natural and cultural heritage they contain. Those agencies also are complex hierarchical organizations with broad geographic distribution.

The plot is made of two intertwined subplots that end up being connected, although we didn’t know that at the start.

Innovation and creativity happen when the need arises and the need arises frequently for government employees and citizens to either conflict or collaborate. Civic engagement aims for collaboration. We undertook a small-scale study of how that was happening in our agency. We hoped to get a detailed snapshot and thought we might find some common strategies.

Instead, we found widespread invention of different strategies, all them depending upon a few core principles. One subplot, then, follows the actions taken by both employees and citizens in each of the case studies. The moral of that part of the story is the revelation that concepts trump tactics. The conceptual principles discovered in every case did not come from any kind of manual or training. There is no civic engagement cookbook. Instead they came from common purpose.

The other subplot – and maybe there is more than one – is just getting started, but it begins with the insight that the core principles of successful engagement across the government-citizen border can guide us to successful engagement across internal borders, across the stovepipes, and across the hierarchy. This part of the story potentially has many morals, including the moonshots chosen above.

The trigger to getting this study done was the long-standing commitment of a grass roots and persistent coalition of employees dedicated to improving engagement with citizens. It’s both as simple and complex as that.

Anthropologist Michael Agar (2007) proposes that the role of the central office should be to learn from field innovations, support them, and communicate them to the rest of the field. That’s exactly what we’ve tried to do with this study.

Anthropology graduate student Molly Russell (2011) systematically collected 15 case studies from several different program areas, coded them, and used a standard method of qualitative analysis to tease out the core principles and secondary principles. In conjunction with the study, we created an active community of practice around civic engagement in the central office.

One of the key innovations was the extent to which we cross program areas, those infamous stovepipes, which we blame for so many failures of communication.

Agar, who has worked extensively with the public health field, discovers over and over again that asking the top levels of a bureaucracy to change based on what is learned from the “lower levels” gets nowhere.

But why? Who in the bureaucracy benefits from the status quo and how? In his experience: “giving up some control in service of better performance had little appeal to the top of the bureaucracy” partly because the “powers that be want a plan, predictability, stability over time, equilibrium, long-range outcomes that can be measured.” (2007:83) He observes that, while the premise that front line folks know more about what needs to be done may get lip service, it is inefficient from the viewpoint of those who make policy and budgets. The central office wants standard procedures and indicators that apply everywhere in the same way.

But more than centralized control is at issue, organizational structure with its institutionalized reward and prestige system, is the most stubborn blocker. Agar (2010) observes that lasting innovation requires a fundamental change in structure. But those who control capital – not only material, but also symbolic, social, and cultural – have a vested interest in blocking such change because they might then lose capital. Agar concludes that the outsider’s influence (in his case as researcher/consultant) is likely to end when such change is recommended. An outsider cannot impose change that the structure cannot handle.

If an outsider cannot impose change, what about insiders? Where do they have to be placed? What about many outsiders when those outsiders are citizens? Whose ideas/demands get heard, and from what directions?

The question raised here is how can active and effective citizen engagement crack the organizational structure so that it works better for the greatest good of the greatest number over the longest period of time?

How do we measure the functioning of participatory democracy?

Identifying core and secondary principles was far more important than the specific tactics.

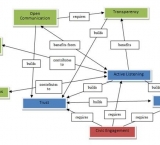

The Core principles are Trust, Relationships, and Active Listening. The secondary principles, while very important in supporting core principles, are not individually essential in every engagement. Those are Diversity of opinion, Understanding communities, Open communication, and Transparency (Source: Russell 2011). In the image below, core principles are in blue, secondary in green.

Get enough people together working on a common goal, labeling it in common ways and start to change the organization from inside as well as letting it be changed from the outside to meet the needs and desires of citizens who want to have input and participate.

Agar, Michael 2010 On the Ethnographic Part of the Mix; A Mulit-Genre Tale of the Field. Organizational Research Methods 13(2):286-303.

Agar, Michael 2007 Rolling complex rocks up social service hills: a personal commentary. E:CO Issue 9(3):81-90.

See also Michael Agar 2005 Telling it like you think it might be: narrative, linguistic anthropology, and the complex organization. E:CO Issue Volume 7, Nos. 3-4 2005, pp. 23-34. Available on his website: http://www.ethknoworks.com/

Argyris, Chris 1993 Knowledge for action: a guide to overcoming barriers to organizational change. Jossey-Bass.

Russell, Molly 2011 Principles of Successful Civic Engagement in the National Park Service. Studies in Archeology and Ethnography, Number 7. Department of Interior, National Park Service, Archeology Program. http://www.nps.gov/archeology/PUBS/studies/PDF/study07.pdf

The full study is attached. See also http://www.nps.gov/civic/

You need to register in order to submit a comment.