With traditional policing practices challenged by a rising rate of criminal activity and tight budgets, the Memphis Police Department pioneered a way to focus our patrol resources more intelligently and restructure the way the department works. Our program for reducing crime, Blue CRUSH, is more than adopting a new technology—it’s an evidence-based, comprehensive change of the department’s culture that has had a dramatic impact on how we work together, our relationship with the community and how we fight crime. The department now focuses on the management principles for driving innovation by breaking down organizational silos, de-emphasizing hierarchy, pushing accountability and developing collective intelligence.

As the 16th largest police department in the nation, the Memphis Police Department is one of the most progressive in the nation—creating an open-information culture that removed silo behavior, de-emphasized hierarchy and drove collaboration between departments and the extended community to dramatically reduce crime. Our 2,470 officers protect 670,000 citizens in the metro area’s nine precincts. The department also employs 441 civilians including dispatchers, police service technicians, administrators, mechanics, clerks, neighborhood watch coordinators and school crossing guards.

Crime has become more sophisticated with each passing decade—but so have our crime-prevention tactics based on advances in our organizational management and use of new technology. MPD has enhanced our “who-done-it” crime-fighting techniques with IBM predictive analytics software to thwart criminal activity and become smarter in managing our policing efforts.

By recognizing crime trends as they happen, our predictive enforcement tool gives precinct commanders the ability to change their tactics and redirect their patrol resources in a way that puts officers in the right place at the right time to more effectively apprehend criminals, and in some cases prevent crimes from happening altogether. The development of the Blue CRUSH (Crime Reduction Utilizing Statistical History) program not only changed the way crime is fought but how these efforts extend into collaborative community revitalization programs. Through such smart policing approaches, we’ve reduced the overall crime volume in Memphis by 30 percent, making life safer for citizens.

In 2005, the mayor of Memphis realized our city had a problem with rising crime rates that were upsetting citizens and holding economic progress hostage. So he approached MPD to get the city’s crime issues under control. Larry Godwin, the former director of Police Services, convened a meeting of MPD command staff and other key personnel to stimulate fresh ideas on how to reverse this rising tide of crime. During what was affectionately known as the “cafeteria summit,” key members of the Command Staff and the department’s Organized Crime Unit (OCU) sat down with District Attorney General Bill Gibbons (whose district included Memphis) and Dr. Richard Janikowski, a professor of criminology at the University of Memphis. Together, the team sketched out a scenario of our current crime situation and the goals we’d like to set:

- Reduce the rate of rising crime

- Do more effective policing despite frozen (or sometimes even shrinking) budgets

- Help Memphis citizens feel safe despite growing disenchantment

Needless to say, MPD was open to ideas. As director of the university’s Center for Community Criminology and Research, ideas were Janikowski’s specialty. Over the decade before, he had been involved in a number of analytical initiatives into better understanding crime patterns. Now, with the MPD requesting his input, Janikowski saw the opportunity to put into practice the simple yet powerful principle of focusing police resources intelligently by putting them in the right place, on the right day, at the right time. In this way, you’ll either deter criminal activity or you’re going to catch criminals.

Getting Approval Top Down

The results of the pilot program were a great start, but only a start. We needed to secure mayoral approval to move ahead with the program. Top MPD leaders prepared a business case that resonated with the brutal budget realities that Memphis shared with most major American cities—the need to confront a growing problem with fixed or shrinking resources. It was widely acknowledged that the MPD needed to add another 500 patrol officers to offset a growth in criminal activity, but that would take nearly six years to achieve.

The aim was to show how the intelligent alignment of police resources would effectively enable the department to close the manpower gap--a must in the eyes of Memphis’s citizens. Under the proposed plan, each precinct commander in the MPD would be given the resources (in the form of overtime funding) and flexibility to make their own deployment decisions based on intelligence provided by the solution. Results would be rigorously measured and commanders held accountable for their performance. Lucky for us, doing our homework and having the pilot results to back up our plan meant we didn’t have to do too much selling—a few hours after our pitch meeting, the mayor called a press conference to tout the newly approved program. After eight months, the success of the pilot program—with documented crime reductions of 30 percent or more in pilot precincts—led to a decision to expand the program city-wide in 2006.

Anatomy of a pilot

We developed a pilot process after the cafeteria meeting. We realized it was important to test both the data analytics, methods for displaying the data in a manner most useful and understandable to commanders, first line supervisors, and line officers who would be on the street.

- The initial stage involved developing and producing and analyzing data packages for a core planning group via a series meeting with the data analysis. These meetings also included discussions of evidence based-practices, including discussions of what works. After reaching consensus on a preliminary data package, the planning team recommended a series of large scale operations focusing on certain areas of the city which the data revealed as having hotspots of criminal activity.

- The first operation was launched in August 2005 and resulted in more arrests being made within a three hour time frame than at any time in its history. While the operation had to be curtailed early because of a shortage of transport vehicles to take prisoners to the jail, initial results were encouraging. The University of Memphis spent the night tabulating and analyzing arrest figures in order to provide quick feedback to commanders and units involved in the operation.

- Over the next few days debriefing sessions were held with commanders, first line supervisors, and officers involved in the operations to obtain feedback on what worked, what didn’t, and what improvements could be made to both data analysis and operational structure and tactics.

- The University of Memphis team also analyzed post-operation crime daily and weekly to evaluate operational impact in the targeted areas and provided the results to the various commanders and units over a period of two weeks.

- Involving participants in critiquing and making recommendations for improvement was critical. Subsequent operations followed the same pattern of planning, implementation, and the debriefing followed by incorporation into each subsequent operation relevant findings.

- Results of these large-operations, led to implementation of pilot operations in two selected precincts to develop a plan for integrating Blue CRUSH into normal Uniform Patrol precinct operations.

- The true test of the strategy was integration of the new data analysis and evidence-based practices into normal operations. Large operations also garnered substantial media attention and an outpouring of public support.

- Discussions were specifically targeted at breaking down silos and stressing a new mission message that “CRIME REDUCTION WAS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF EVERY POLICE OFFCIER” NO MATTER WHAT UNIT THEY WERE ASSIGNED TO (Traffic, Canine, TACT-MPDs SWAT team, etc.)

Changing Information into Actionable Knowledge

As part of the plan, we agreed to regularly share key crime data with Janikowski and his colleagues—a gesture that goes against the deeply ingrained tendency of a lot of police departments to hold their information close. Using this crime data, Janikowski’s job was to develop an analytical framework that would be used as the basis for a pilot program, the results of which would shed light on which analytical and operational approaches worked and which didn’t.

Janikowski and his team, using IBM predictive analytics software, helped the department develop new statistical analyses that would not only do a better job of fighting crime, but would change the culture of the department by giving us the tools to share data openly and to greater effect. At the same time, the department—with assistance from Janikowski’s team—assessed our organizational structure, deployment and effectiveness of investigative bureaus and specialized units, and the internal mechanisms for assuring accountability and responsibility within the department. The results of this assessment became the foundation for a new business model involving an organizational commitment to data-driven decision-making and management. In conjunction with this new business model, we developed an evidence-based strategy for cultural change within the department. Realizing that untested city-wide initiatives often fail because of implementation problems and lack of support from line officers, the department launched a time-limited pilot program to allow for experimentation with analytic techniques and new tactics and units.

Keeping the Team Accountable and Cohesive

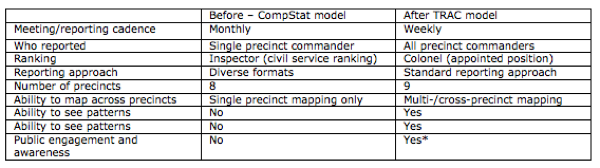

In the old days, MPD used the traditional “CompStat” approach to department management which was originally developed for the City of New York. But Memphis wasn’t New York and didn’t have 43,000 police officers or an entire unit to do statistical analysis.

Back then there were eight precincts, and once a month a single precinct commander would be on the hook to report results and be grilled by a deputy chief. A lot can happen in a month. Not only that, there was no standardized form of reporting so selective interpretations of crime could occur. Even worse, no one took notes, which prevented accountability and the development of institutional memory and experience. Finally, precinct commanders held a civil service rank, so finding alternative positions for those who weren’t performing was a challenge.

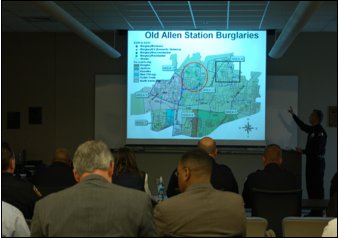

Today, MPD has weekly TRAC (Tracking for Responsibility, Accountability and Credibility) meetings where precincts commanders go over results with the command staff and peers to judge what worked, what didn’t and how to adjust tactics in the coming week. Blue CRUSH lays bare underlying crime trends in the way that promotes an effective, fast response, as well as a deeper understanding of the longer-term factors (like abandoned housing) that affect crime trends. We might see, for example, how burglaries are down in one ward, but up in another, or where thieves are stealing cars in one ward and dumping them in another. As our analytic methodology continued to evolve, we were now catching trends immediately on a daily basis and able to shift officers to a particular ward on short notice—and we were making arrests we could never make before. In addition, to the weekly command TRAC meeting, each individual precinct holds its own weekly TRAC meeting to develop plans, share tactics, and monitor progress with supervisors and officers.

Weekly TRAC Meeting

* As the model has evolved community participation in the meetings has changed to allow for greater sharing between precinct commanders on sensitive matters. However, initial TRAC meetings encouraged broad participation by lieutenants, patrol officers and members of the public to increase awareness of the program and direct linkages to complimentary community meetings.

The goal was to encourage the commanders to learn from one another—if a crime-fighting approach was effective, commanders would share knowledge. They also learned openly about approaches that were less effective without fear of retribution. Today we encourage a healthy competition between the precincts and this has led to data-driven precinct redistricting as a means of equalizing the call loads across the wards and reduction of crime. This redistricting approach deployed the forces more effectively and took into account: types of crime, population demographics and even geographic factors such as whether natural phenomena like rivers hamper effective police response times. The original district boundaries were based on maps from Memphis gas and electric services. The new districts are based on a much more balanced approach that evens the playing field across the city for fighting crime.

It’s the goal of the MPD to find ways to encourage the entire force to work together. In fact, a few years ago, the department changed a uniform policy in which officers in the field wore blue shirts and leaders on the force wore white, to a policy where all officers wear blue shirts. We wanted to send the message that the MPD operates as a team. We needed to shake hierarchical thinking and remember that every member of the force has a role in fighting crime. This willingness to try new approaches was what allowed the MPD team to fight crime more effectively in recent years.

Deployment Timeline

The Blue CRUSH (Crime Reduction Utilizing Statistical History) pilot began with changing the way data was analyzed and testing new tactics and unit configurations. Shortly after Blue CRUSH was announced in 2005, MPD conducted a series of test pilot operations in selected precincts before rolling out the program city-wide. We used data analysis of past and current crime information provided with IBM SPSS predictive analytics software to evaluate incident patterns throughout the city—in areas as wide as the city’s entire nine precincts or narrowed down to a single block. Maps and charts of crime patterns were generated based on type of criminal offense, time of day, day of week or various victim/offender characteristics. These maps were then used to specifically focus investigative and patrol resources with the goal of taking back neighborhoods one street at a time. The initial results were staggering and quickly validated our strategy.

- In August, Operation Blue CRUSH took place in select precincts. In less than 24 hours time after the operation began, we arrested nearly 67 people for an array of offenses, particularly drug charges. The 67 arrests marked a new single-day record for MPD. Our department went on to report a six percent decrease in similar crime activity in those areas following Operation Blue CRUSH. This success was a tremendous boost to morale for officers and proved out the value of the approach for those who had been skeptical or reluctant to change routine and share their data immediately from the field

- From September to October, MPD conducted Operation Safe Haven, which focused on Hurricane Katrina evacuees in Memphis who were being targeted by local criminals. MPD identified areas of the city that were most likely for this type of crime and responded with added patrols. Operation Safe Haven reduced these targeted crimes by 85.7 percent. It also acted as a further proof point to garner support for the program internally and within the community.

- In September, MPD placed added emphasis on the escalating rate of crimes involving Hispanic residents with the introduction of Operation Colaboracion. During September 4–10, MPD noted that 84 robberies were reported within the Hispanic community, up by 49 cases over the previous week alone. Blue CRUSH technology determined which areas of the city were most likely for this type of crime, as well as the time of day they occurred most, day of week and other victim/offender characteristics. After Operation Colaboracion, MPD observed a 71 percent decline in robberies involving Hispanic victims. These actions built considerable goodwill within the Hispanic community in addition to adding to the department’s success rate overall.

- Pilot operations in the select precincts tested new data analysis designed for commanders, supervisors and patrol officers, along with new evidence-based tactics based on extensive best practices research. Blue CRUSH analysis was used to identify evolving crime hot spots and to develop plans for addressing these hot spots with enhanced patrols, directed taskforces and coordination with specialized units. These pilot operations were designed to foster cultural change within the organization by breaking down “job boxes” within units, like uniform patrol responding to calls for service, traffic writing tickets, K-9 doing random patrol until called to assist with a hidden suspect, etc. Instead, the department now emphasized that crime reduction was every officer’s responsibility and that units (including specialized units) would be deployed and efforts coordinated by using data and information to target crime hot spots.

- The assessment of bureaus and specialized units led to the reconfiguration of some units and much closer coordination of resources among bureaus, specialized units and patrol precincts. As an example, in January 2006, MPD created a new unit, the Criminal Apprehension Team (CAT), to expand the resources of Blue CRUSH. This unit, located within the Organized Crime Unit, was staffed with a cadre of experienced investigators and is used in an integrated manner with other units, focusing on both problematic crime and known high-crime areas inside Memphis. CAT encompasses the Hispanic Action Response Team and former members of the Metro Gang Unit working in cooperation with Project Safe Neighborhoods and the Auto Cargo Theft Task Force. Its focus is on street-level crimes where crime patterns and/or specific problematic crime areas have been identified by Blue CRUSH methodology. CAT also works closely with uniform patrol divisions, investigative services bureaus and crime analysis unit to ensure departmental resources are being utilized efficiently and proactively.

- Using data to identify weaknesses in investigative bureaus led the department to create the Felony Assault Unit (FAU). Our assessment determined that the clearance (solve) rate for Aggravated Assaults (those involving a weapon or serious injury) was an unacceptable 16 percent. From the assessment, it became clear that assigning aggravated assault cases to the General Assignment Bureau, which handles all investigations except for homicide, sexual assault, burglary and economic crimes, resulted in insufficient attention to this very serious crime. Addressing this challenge involved the creation of the FAU, staffed with experienced investigators tasked with concentrating on these assaults. As a result, within six months the solve rate for Aggravated Assaults had increased to more than 70 percent.

Empowering Analysts to be More Innovative

As part of the city-wide expansion, we reconfigured of the Crime Analysis Unit into a centralized unit working out of a newly developed Real Time Crime Center. By working collaboratively, the analysts were able to expose new patterns and series of crimes. Instead of producing a one-inch thick report that no one could reasonably read, we created daily diagnostic reports using IBM predictive analytics tools, that showed whether crimes were falling within the projected focus areas. Both civilian and officer analysts were initially trained by Janikowski’s team in advanced statistical and spatial analysis. During the process, we completely restructured the interactions between our analysts for each precinct and gained broader perspective by drawing from the insights of both officers and civilians.

MPD’s Data Control Center

With the old model, we used a third-party tool that essentially did the crime analyses for the analyst—they would just type in a date range for a predetermined polygon and click a button. The tool would automatically build the crime stats, but only within the limited range of the geographic area described by the polygon, preventing analysts from seeing crime patterns that extended beyond the boundaries of an individual precinct. Analysts were also unable to develop new analytic techniques or adopt new information displays. Moreover, the system didn’t save the geo-coded addresses so they would have to be re-run for each successive analysis—this provided the analysts no insight concerning the percentage of addresses that had been successfully geo-coded.

Following the training with Janikowski’s team, crime analysts were much more empowered by the ability to do their own geo-coding, which was then saved for later use. Analysts expanded their toolbox of analytic techniques, developed new methods of displaying information and adopted a variety of methods to maximize information sharing among commanders and line officers (including the availability of online data tables and maps). Working with Janikowski’s team, the analysts also designed new address locators which pushed the geo-coding rate of addresses from 60 percent to 95 percent. While some analysts initially resisted having to share domain expertise and move to the new analysis tool, they’re now much more effective and gratified in their jobs today. The crime analysis unit has gone from a group of individuals performing rote tasks to a team sharing insights, innovating new analytic techniques, and constantly exploring new models for data-sharing and displaying information in ways that are most useful for commanders and officers. Our analysts have said if they could go back to the old way of doing things they wouldn’t.

While it took a while for analysts to see how this bold new approach could benefit them and the department, the additional training was the clincher—it spread knowledge not only across the police department, but to the fire department, EMS and others services. It also opened up a strong partnership between the University of Memphis and law enforcement. When the department shares data analysis with the community, it has the validation of the university behind it as well.

Based on our initial successes, we secured grant funding for further training—not only for our team but for analysts across the Mid-South. Our analyst team also recently won first place in crime mapping in a competition sponsored by the International Association of Crime Analysts—an organization of 2,400 crime analysts around the world. There’s no way the team would have had the skills or tools to accomplish that using the old system and approach.

Open Conversations Lead to Buy-in from Officers

Learning from in-field mistakes and expertise was only one part of the rollout process for garnering officer support. The other critical element for creating an open-information culture and de-emphasizing hierarchy came with the engagement of deputy chiefs doing in-service training presentations about the Blue CRUSH program. We knew we had to obtain the support of commanders and particularly, line supervisors and rank-and-file officers—without their buy-in and use of the data and new tactics, even the most sophisticated data analysis and organizational change would have little impact. Every officer is required annually to complete 40 hours of in-service training; deputy chiefs conducted briefings during these in-service sessions explaining what we were doing with Blue CRUSH, why we were doing it and what we hoped the results would be. During those meetings we took questions, shared answers and discussed suggestions. Most of the participants had never seen a deputy chief reaching out to discuss a process change in detail, much less solicit suggestions and ideas on a new strategy. The pilot operations provided important support for the new strategy—both in terms of successful outcomes and, just as importantly, the positive observations given by officers who had participated in the pilot precincts. When one of their own supported the idea, the entire climate in the room changed—it was no longer just a theory but something that had been proven to work. The process was repeated during a second year with an emphasis on obtaining feedback from officers on what was and wasn’t working, what could be improved, and to solicit new ideas and approaches.

Giving Police Reports New Significance

In many ways, police records management systems are like electronic filing cabinets—designed to store information on each individual case with little capacity to provide a platform for data analysis or information sharing. Police officers often viewed the incident and arrest reports they completed as going into a black hole. They wrote up a report, and it got filed in the system—they never saw it again, never used it again. Our goal was to make that information useful. We gave each precinct, for example, crime maps and later crime heat maps—first a paper version, posted in precincts for use by supervisors and patrol officers, and then digitally as handheld PDA technology became pervasive. Having immediate, real-time access to critical data allowed officers to be able to critically asses the data and see how their reporting fit into the big picture.

The pilot program rolled out gradually, and the analysts and officers communicated regularly to fine tune what information was critical and how it should be shared for greatest impact. Most importantly, participants from the early pilots played a critical role in validating the work and giving feedback that helped shape Blue CRUSH. By sharing the collective intelligence of officers and being able to showcase dramatic results early on, the program gained traction and credibility with the force and with the community.

But like the analysts, it took officers a while to feel comfortable with the new approach. At the time we first implemented Blue CRUSH, Major Stephen Grisham was a Lieutenant in Uniform Patrol. He, like many supervisors and officers in the field, viewed it as just another program—even busy work. His turning point came when his precinct was experiencing a rash of day-time burglaries where the thief used a brick to break windows. Grisham ran a Blue CRUSH detail with plainclothes officers based on the days and times the burglaries were occurring. The officers jumped the suspect in the targeted area and arrested him. Catching a suspect who’d been causing issues for weeks in one attempt with Blue CRUSH data is what changed Grisham’s mindset on the benefits of using current data to address emerging problems quickly to impact on crime. Grisham has since been promoted and is currently in charge of the commissioned officer crime analysts at the Real Time Crime Center. While he began as a supervisor with little experience in data-driven policing and analysis, he evolved to be a leader in using analysis to address crime problems.

Training at the right time for the right audience

Training meetings served the purpose of planning, results evaluation and operational adjustment AND for training on data use and evidence-based practices: during initial meetings there were formal training presentations and then throughout the meeting process discussions of data, analysis, and best practices were embedded in discussions and evaluations of results and approaches.

With the expansion of the strategy city-wide Deputy Chiefs, accompanied by Professor Janikowski whenever he was available, did training presentations during officer in-service. MPD officers were required to attend a 40-hour POST (Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission) every year. Time was specifically reserved in each session to obtain officer feedback comments, suggestions, and ideas.

- Alumni influence: In almost every in-service there were 1 or 2 officers who had participated in the pilots stood up and said to the group “Give them a chance. We did it and we made a lot of good arrests and crime came down.” This was enough to change the mood in the room- when one of their own endorses the idea then the group at least becomes receptive to the discussion.

- Listening and peer learning: by providing the opportunity to give feedback and ideas the sessions generated increased buy-in. These training sessions were conducted for all officer in-services, supervisors, precinct commanders, investigators, and command staff.

- Partnering with the University: During the first year, the University of Memphis provided the analysis for Blue CRUSH. Thereafter the Janikowski and team developed a training curriculum and training manuals to implement training for MPD’s crime analysis on statistics and crime mapping. The University team also developed a training curriculum for officer analysts being incorporated into the new Real Time Crime Center.

Changing our Philosophy from “Law Enforcement to Community Revitalization”

Putting resources in a community short term may reduce crime, but it’s likely to spill over into other neighborhoods or return to an original hot spot. We needed to think instead in terms of putting resources in a community for longer term and having the department change our philosophy from law enforcement to community revitalization. In this model, the police department becomes a facilitator for the community and other agencies to address broader factors behind crime in the communities.

But to change the way we did business and to make the change to targeted policing in high-poverty and minority neighborhoods, it was critical to explain what was happening and gradually build up trust in the community.

Upon becoming police director, I began the next iteration of our policing management strategy, the Community Outreach Program (COP). In this model, the police department became a facilitator for the community and other agencies to address broader factors behind crime in the communities. To address certain chronic hot spots that need long-term strategies to reduce reoccurring crime, COP sought to engage and maintain public support for this effort by:

- Establishing sustained contact with community leaders and neighborhood groups

- Enabling community empowerment by facilitating and coordinating delivery of critical services by governmental and private-sector agencies to at-risk populations and communities

- Developing diversified and sustained prevention, intervention and enforcement initiatives

- Engaging the assistance of various referral agencies and service organizations when needed

- Recognizing the importance of working to build police legitimacy in the eyes of community members most often plagued by crime yet frequently the most distrustful of police

- Identifying hot spot areas for youth firearm violence to help prevent crimes in young offenders

- Focusing on the human aspect of crimes and listening to citizens—not just data

Going out to our city, we had over 200 meetings—some with five people, some with 200. We did the same thing we had done with officers, explaining what we were doing with Blue CRUSH, why we were doing the program and sharing results. The meetings became a basis for regular community gatherings hosted by precincts to brief citizens about progress made and obtain new insights on neighborhood issues and problems. We received such good feedback during the meetings that our precinct commanders now hold them regularly. The results and increased understanding in the community got not only the support we needed, but letters to the editor, a change in tone in our conversation with the community, and the highest score on citizen satisfaction in MPD’s history in a recent Memphis Poll, a survey conducted by the city regarding citizen satisfaction and perception of city services.

At the outset, our community meetings were focused on information sharing, and eventually they became a way to gather data. Briefings were conducted with community leaders and community groups along the same lines used in officer in-services. Community leaders and groups were identified using a snow-ball technique within each meeting asking about other leaders or groups who might be interested in learning about the strategy. To garner community support we developed a communications strategy to foster outreach with the media, community leaders, and community groups. With the media this involved press briefings with news editors and reporters about the strategy and specific operations. Reporters were often embedded within operational teams or provided the opportunity for an expanded ride-along program with officers.

While Blue CRUSH significantly reduced city-wide crime, we recognized there were still chronic crime hot spots in the city. These hot spots represented disproportionately high concentrations of violent crime, especially firearms-related crime by youth. By incorporating the perspectives of the community and the officers who were on the streets, we were able to look at the day-to-day details in terms of a bigger picture. These included socio-demographics like truancy, poverty, workforce data and challenges associated with problem properties like vacant buildings. Using the Blue CRUSH data methodology, we identified chronic crime hot spots for youth firearms violence and incorporated community policing principles into our strategy to drastically lower these offenses.

In the expanded iteration of hotspot policing I walked the streets talking with residents and community stakeholders about concerns, community issues, and what could done. COP officers have had direct contact with over 3,000 people in the two neighborhoods to collect data and information and build relationships of trust and cooperation. Officers also attend community meetings and events and sponsor health fairs, recreation days in parks, sports leagues, and other activities to facilitate communication and relationships.

In 2008, we set up a sting operation at two sections of Lamar Avenue on either side of Interstate 240. We cited 64 men for misdemeanor patronizing prostitutes. But about 40 of them also had their cars seized under a state law that allows the seizures and possible forfeiture. We held a press conference the next day and had several dozen of the seized cars out on display with “OCU” (Organized Crime Unit) written largely in white paint across the windshield. The public was able to see the tangible results of our strategy to target hot spots, and our office was flooded with calls from neighborhood groups asking for the same type of operation in their areas.

In another example when members of the Organized Crime Unit were having breakfast following an operation closing a crack house , a community group of twenty residents approached them told them the officers they wanted to thank them for their work and asked if all the members of the group could shake the officers hands. Similar instances of resident appreciation occurred throughout the city.

The Community Outreach Program in Action

Peggie Russell, a community volunteer with an organization called "Stop the Madness" was working on developing collaboratives with law enforcement and other community organizations to address youth violence. As part of our community outreach in Blue CRUSH, we began to work with Russell and others to promote and support community mobilization around the issue.

Here’s Peggie Russell; “In my current role as Project Manager for the Memphis Gun Down Plan, I work in partnership with the Memphis Police Department to implement a comprehensive strategy to reduce youth gun violence in our city 10% by 2014. The Community Outreach Policing Program has been invaluable in our community mobilization work in Memphis. The COP officers have established relationships with adults and youth in our two targeted communities. This summer the COP officers received complaints that youth were afraid to enter Denver Park because of gang activity----the officers worked diligently with the community leaders and regained control of the park. Over the course of the summer, the officers organized numerous events in the park and helped the citizens maintain a constant presence to ensure the gang activity would not return. The COP Officers established a "Lunch in the Park" feeding program where the young people not only received a much needed meal but also postivive interaction with an adult role model. In August 2012, the Memphis Police Department hosted its first Police/Clergy Partnership Conference and over 130 clergy leaders participated in the event--many of those faith leaders are now actively engaged in supporting various COP activities. When we organize community events such as our January 26th Prayer Walk to End Gun Violence, the COP officers participate with our street outreach and violence intervention teams---and the community members actively engaged in the event.”

Securing Buy-in from Officers

We realized that moving from a pilot project to a systemic change in practices would require broad buy-in, especially from patrol officers out on the street. It wasn’t only a question of communicating how predictive modeling can help our officers be more effective, but also knowing how to listen to them and tap into their knowledge—no one knows a ward better than the patrolman who rides as many as six or seven days a week for eight to 10 hours a day.

While conceived at the top, the success of the predictive policing initiative hung largely on getting patrol officers on the street to take ownership—and that meant a willingness to listen and learn. So we involved officers throughout the process, communicated to them the “big picture” of what we were trying to achieve, and then showed them the results. This tapped into the fact that officers like to do something good and like when the department invests in its people.

We believe the biggest asset to our success from a management perspective was accountability. The experiences of other departments in analytical police work—as well as the MPD’s early efforts—showed us the importance of rigorous and consistent reporting practices, employing common metrics, across precincts. We did this with Blue CRUSH in two ways:

- Equal opportunity reporting builds a strong organizational culture. The first was our decision to employ a standardized reporting template for all commanders, thus discouraging the tendency to “cherry pick” results and obscure meaningful comparisons.

- Build an open culture by sharing ideas and learning from mistakes. Further reinforcing the message (and removing all ambiguity) was the decision to rename the weekly sessions TRAC (Tracking for Responsibility, Accountability and Credibility) meetings. The fact that TRAC meetings are also a forum for precinct commanders to share their ideas—and, in many cases, learn from each other’s mistakes—is an outgrowth of the more open culture we’ve tried to engender.

Organizational Restructuring and Culture Change within MPD

Make no mistake; getting initial buy-in from officers was just the beginning. It became evident that to take advantage of this new analytics advantage, the organization needed to re-tool. MPD and the University of Memphis conducted evaluations that pointed to an outmoded business model that wasn’t working as evidenced by increases in crime. Some of the issues MPD had to address included:

- Outmoded models of assigning police personnel and resources (traditional “random patrolling” and investigative model)

- Failure to take advantage of innovative technology (untrained analysts, a vendor system that prevented innovative analytic techniques)

- Siloed units and compartmentalized thought processes

- Barriers to information sharing (no processes for sharing information or data analysis, for example from precinct to precinct)

- Disconnected tactics (no shared toolbox of resources)

- Lack of accountability (no ability to track results on a consistent basis)

Our approach became Warren Buffet’s idea that, “In a chronically leaking boat, energy devoted to changing vessels is more productive than energy devoted to patching leaks.” Technical problems are the easiest to solve but we needed to resolve cultural/organizational issues. So we created an entirely new business model that allowed us to:

- Retool MPD (create new units and refocus existing units, stress an organizational value where every officer is responsible for crime reduction)

- Adopt data-driven decision making (organizational commitment to analyze and use data products, data-driven interventions and in-service training at all levels)

- Utilize innovative technology (adopted IBM SPSS and ESRI ArcGIS)

- Create structures for information exchange (the need to work as a team, how to best interpret data and share it and identify the questions that need to be answered to solve issues)

- Use data to efficiently allocate manpower and resources (work with officers and commanders to determine what data was useful and understandable)

- Research evidence-based practices (adapt law enforcement best practices to our local circumstances)

- Pilot methods (see what works on a small scale and generate buy-in)

- Create a culture of analytics/accountability (Blue CRUSH TRAC meetings and rank structure change away from civil service inspector to colonel status)

The direct and most significant benefit to the community was a steady reduction in crime rates, which attested to the fact that more police presence tends to reduce crime. The fact that we were able to increase police presence on the street and eliminate “random patrolling”—without increasing our overall manpower—is what makes this “smart” policing.

The benefits of MPD’s predictive crime prevention practices:

- 30 percent reduction in serious crime overall, and 20 percent reduction in violent crime. For example, the city’s robbery rate declined over twice the decline for the entire nation since 2006 and the burglary rate was reduced almost five time the rate for the nation as a whole

- Action to target drug dealers in a specific neighborhood produced 50 arrests and led to a 36.8 percent reduction in crime in that area

- 4x increase in the share of cases solved in the MPD’s Felony Assault Unit (FAU), from 16 percent to nearly 70 percent

- Overall improvement in the ability to allocate police resource in a budget-constrained fiscal environment

- Zero additional cost to taxpayers: even as the municipal budget has shrunk precinct commanders have adapted tactics and patrol methods to maximize the impact of their resources through enhanced data analysis

- Partnership: the use of Blue CRUSH is providing maximum return on investment for our citizens through the partnership by which data analysis and evidence-based practice is facilitated by the University of Memphis’ Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice

Benefits to MPD

Like many government agencies, we were continuously asked to do more with less. In a tight economy, it was more important than ever to deploy resources wisely and proactively—and intelligence from IBM predictive analytics software helped us do just that. MPD officers say that today precincts can more cost-effectively manage deployments, focusing resources where they’re most needed and avoiding unnecessary overtime pay. Among other planning tools, precincts are now drawing on predictive analytics to prepare "productivity sheets" that set specific law enforcement goals and track performance from week to week, helping keep teams on track.

Benefits to Patrol Officers and Citizens

At the weekly Blue CRUSH TRAC meetings, officers are now better informed about which areas are predicted to be the most at-risk for crime. They’re given bullet point lists of what particular crimes to watch out for and when, empowering them to take a more proactive role in the city’s ongoing commitment to crime prevention and public safety. This has been a huge boon for morale. This is what our officers do, it’s what they love. They’re excited about this program because they’re making positive arrests and seeing dramatic results, all while helping people. As we move forward detectives are also being moved into the precincts. For the past 25 years, detectives answered to chief of detectives at headquarters. By moving them back out to the precincts we enable them to answer to the precinct commander. This will eliminate arguments between task force and bureau. As we give precinct commanders greater autonomy and accountability we also are giving them greater control. With the ability to investigate crimes in real time, investigators can start working on the crimes immediately. We expect that our solve rates will go up tremendously.

Benefits to Citizens

The true impact of Blue CRUSH is seen on a human level, in the improved safety and quality of life of the citizens of Memphis. For example, with these new reams of police report data—times, locations, descriptions of the assaults—MPD can glean some impressive insights. When we looked at data for nearly 5,000 rapes, we were able to uncover that many of the assaults happened when victims left home at night to use payphones mounted outside convenience stores. As a result of seeing a pattern that would have been nearly impossible to detect without predictive analytics, we asked convenience store owners to move their payphones indoors and we saw the rape level in Memphis drop. The 30 percent reduction in crime the MPD was able to achieve through intelligent policing is not just a number—it represents hundreds of people who did not experience crimes, who didn’t have a gun put in their face or have their homes burglarized. That makes a big difference in people’s lives.

Changing How Police and the Community Work Together and with Each Other

Billy Garrett, now retired, was a precinct commander who became one of the most capable commanders in our department and he was promoted to Colonel. He acted as a role model for new precinct commanders, and taught them how to effectively use data within the Blue CRUSH model.

Garret describes the old day to day precinct routine as: roll call, read out of department directives and “tell the troops to hit the streets.” “There was no organized method or plan to attack the crime problems MPD was experiencing. For the many years leading up to Blue CRUSH, the standard approach to address crime was to have a good response time, to get on the scene quickly. Officers would make the call, but then leave with no follow up or no collective data keeping. Every unit within the department worked independently of each other and was very ‘territorial.’”

Precinct commanders, like Billy, have to motivate the officers and take the message of public safety to the community and gain their support and involvement. Blue CRUSH caught on in the community because it “made sense.” Officers encouraged residents to report all activity, whether it was a crime or not. Working with MPD, residents saw a way to make a difference and the quick results made the difference in getting involvement from everyone.

Officers bought into the initiative saw the decrease in crime first hand and got positive feedback from citizens. MPD’s visibility on the streets increased when we brought all the departmental resources together, for the first time, like horse patrol, bike patrols, traffic units, Tact units, Canine Units, Narcotic Officers and officers working overtime to one targeted area, actually knowing who, what, when, where and how. Everyone had the same marching orders.

Here’s Billy Garret; “Officers were given specific tactics to use, such as, plainclothes spotters, high visibility, decoys, warrant sweeps, traffic stops with a focus on stolen weapons and drug seizures. We knew where to go and what to do. In addition to our tactics, we use the latest technology. Sky Cops, Pole Cameras, Mobile camera systems, License Plate Readers, FLIR devices installed in squad cars(infrared sensors to help find suspects hiding in bushes and drainage ditches). The department then developed community awareness programs like “Stow it Don’t Show it”. This program reminded citizens to put away items in their vehicles from plain site or to remove them from their vehicles after parking, which helped us to reduce car burglaries. Our citizens even organized with an email communication system among neighborhoods and formed a community involvement group called Midtown Security Community (see blog site). I met monthly with community residents and business owners to give the Blue Crush crime report for our midtown area to large crowds. Share crime stories and prevention strategies.”

Key Lessons

- Every officer plays a part in crime prevention

- Earn collective buy-in by allowing everyone to be a part of the process

- Equip patrol officers with the information they need to do their jobs to the best of their abilities to maintain morale and keep citizens safe

- Creatively find ways to do more with less—don’t let budgetary shortages stop what needs to be done

- Find ways to engage the public so they can take an active role in the success and safety of their city

- Start with a pilot program to produce strong initial results and help secure support

Lessons That Extend Beyond Policing

- Starting with pilots and iterating constantly is key

- Develop a culture that is willing to learn from its mistakes

- Share successes often and broadly

- Nobody likes to change –strong training and redundant communication is key

- You need internal advocates or champions—people who have the power to get funding and support a project

- You need external advocates and champions to provide long-term political and fiscal support

Our pilot approach works by starting small at the departmental or the community level instituting programs that have a specific purpose—be that making parks safe or addressing a rash of burglaries. We do our homework, analyzing specific data patterns and working with the community needs. Even projects that seem small are always part of a larger ecosystem so you have to understand the dynamics that are at play. From there we build on the basis of an open dialogue internally and with the community.

When it comes to training it has to be done in stages and again with an eye to the whole system at play. Being able to collaborate with Dr. Janikowski at the University of Memphis has been invaluable. As he knows better than most , crime analysts are not trained the same way as beat officers but both rely on each other to get the job done. With the analysts we gave them multiple courses—it was not just a simple “one and done” approach. Over time they honed their skills and as they saw the results not just in community policing but as role models for their peers. For the officers, training happened across multiple dimensions: formal training, seeing first hand the key information they needed on a PDA and of course the experiential learning working with their peers and members of the community. The key is to have an open approach that is both systematic in holding people accountable and supportive of a broad range of adaptive approaches. Finally, having peer support and seeing results are critical to success.

Here’s how Major Stephen Grisham puts it: “The city went through a period of not hiring enough officers, but they supplemented the lack of officers with Blue Crush overtime that went to each station to use in addressing crime hot spots. The Colonels used this overtime in agreement with the police union, by placing their most productive officers in these overtime details. These details would target crime patterns addressing specific crimes with specific times and dates provided to the stations by the Crime Analyst Unit. The details proved to make a major impact on each stations crime. This encouraged those officers that had seen their past efforts go unnoticed to increase their productivity. Since the inception of Blue Crush the norm changed from a coasting attitude to a proactive attitude with officers assisting supervisors in holding their co-workers accountable.”

Over the years we’ve welcomed representatives from not only other departments within the United States but Great Britain, Peru, Estonia and the Netherlands, as well as Chilean and Japanese ambassadors to see what we’ve done in Memphis. We believe these principles of management are valuable only to globally policing efforts but across public and private sector contexts as well.

Special thanks to the Memphis Police Department Crime Analysis Unit, Richard Janikowski, Associate Professor, Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Memphis for his continued partnership with the Memphis Police Department and his commitment to keeping the city of Memphis and its citizens safe. Special recognition for Dr. Phyllis Betts, Associate Professor and Director of the Center for Community Building and Neighborhood Action at the University of Memphis for her groundbreaking work in incorporating new types of social, housing, and workforce development data into policing efforts to reduce crime and promote long-term crime reduction through prevention and intervention strategies. And thanks to Bob Reczek at IBM for his ongoing championship of our department’s transformation.

Memphis Police Department Website

Smarter Planet Leadership Series Memphis Police Department Case Study Web Portal

http://www.ibm.com/smarterplanet/us/en/leadership/memphispd/

Smarter Planet Leadership Series Memphis Police Department Case Study Video

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_xsffIAHY3I

Smarter Planet Leadership Series Memphis Police Department Case Study PDF

http://www.ibm.com/smarterplanet/us/en/leadership/memphispd/assets/pdf/IBM_MemphisPD.pdf

Scientific American Article: Ride Along with the Memphis Police Department Pre-Crime Unit [Video]

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=precrime-ride-along-memphis-police-department

Predictive Analytics - Police Use Analytics to Reduce Crime [Video]

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ZyU6po_E74

Photo of Memphis Police Director Toney Armstrong (photo credit: Candice Ludlow)

As crime has become an innovative industry itself, and highly capitalized, you are so right to get into this data mining and statistical tactic.This is your only chance to outsmart the bad guys at least part of the time despite your shrinking means. Very well documented.Keep going.

- Log in to post comments

You need to register in order to submit a comment.