Story:

Inside Whirlpool's Innovation Machine

Mention the word “innovation” to any of Whirlpool Corporation’s 70,000 employees, and he or she will not typically cite any particular product, service or line of business. At Whirlpool, the term innovation broadly refers to the management system that drives a continuous flow of new ideas from concept to consumer. For more than a decade, Whirlpool has continually broadened its view of innovation…from simply “generating new ideas” into a multi-dimensional view of its business and consumers – from the very micro level of a single idea to broad strategic goals. At each stratum, the company relies on structure and process to understand not only where the cadence of innovation is, but also where it should be.

With a history of 101 years, Whirlpool Corporation leads an ultra-competitive and mostly mature industry from a small town in southwest Michigan. Our 70,000 employees generate over $19B in annual revenue by designing, engineering, marketing and selling consumer solutions in more than 135 countries.

After 90 years of constant growth and invention, Whirlpool was looking for a platform to enter the 21st century in a stronger position, we achieved this by focusing on driving consumer preference through innovation – everyone at Whirlpool would be part of that. During our first ten years of striving to embed innovation as a core competency, a major acquisition followed by the recession posed new challenges. Emerging competitors in recent years require us to behave differently. Our 13-year quest for an embedded innovation approach has answered these challenges with creative approaches that have allowed us to stay focused, relevant and competitive. One would think that after the big-bang approach to embed innovation in the early 2000s we would be in auto-pilot by now, but each phase has required the same level of attention from the innovation architects (those creating blueprints and building innovation capability) to take innovation to new heights.

In 1999, Whirlpool CEO David Whitwam began the transformation of Whirlpool. His vision: to transform the firm from a manufacturing driven organization to a consumer driven one, primarily through the lens of innovation from everyone, everywhere. Whirlpool would strengthen its position as leader in new products, services and business lines that would give meaningful reasons for consumers to purchase its products and come back to our brands over time. We would invest in new, perhaps costly features that consumers would be willing to pay for.

This conclusion was more controversial at the time than one would think. Leading with innovation required a faith that consumers would in fact reward innovative products and services by paying price premiums. This was a counterpoint view to an industry racing toward cost efficient but very homogenous product lines. Additionally, it required that Whirlpool take scarce resources from its ongoing business and technology groups to come up with product and service innovations.

Innovation, however, would not be a one-time event. Nor would it be a company-wide temporary priority, nor a separate skunk works. Innovation would become a core competency at Whirlpool, spread across everywhere and at all levels. Most importantly, innovation would not be left to engineers or businesspeople randomly finding a “eureka!” moment for the world’s next great invented home appliance. Innovation would be organized, structured, planned…and to the extent possible – predictable.

The idea of predictable innovation results, when any particular innovation is as yet unknown, is not an intuitive concept; but it is possible. To get to that kind of reliability does require a uniquely structured set of processes and metrics across the spectrum of innovation activity: from generating new ideas to predicting new ones several years out. This is Whirlpool’s unique strength in innovation, and why we now consider it a core competency (albeit, one always under development).

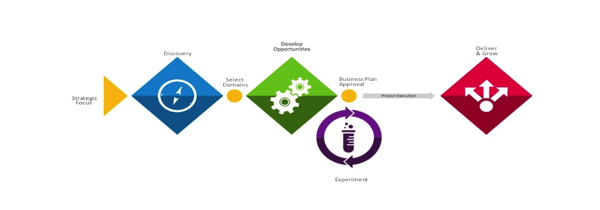

At Whirlpool there are structures and processes to manage innovation work. The development of a specific innovation typically follows a flow:

- Idea generation

- Basic business case formation

- Competition for development of the idea

- Testing and experimentation of the ideas

- Large scale commercialization

At each point, Whirlpool expects a survival rate of 10 to 1. E.G. for every ten good ideas, one will be developed into a business case; ever ten market experiments will lead to one scale up, and so on. This “theorem” is more attitude than science – we simply accept that most interesting ideas do not pan out. Moreover, this is why we continually drive our system to keep producing new ideas.

While the rough process flow above is the path of an individually developed idea (a bottom’s up micro view) there is also a “top down” (macro) view of innovation. A set of tools, metrics and goals that look at our innovation efforts broadly across the organization – where in aggregate are we putting our big bets? What are the technology investments that drive the most new opportunities? What is our pipeline for the next three years?

First, we will look at what happens at the “ground level” – how we create good ideas, instead of waiting for them to pop up.

IDEA GENERATION AND DISCOVERY: STRUCTURED IDEAS, NOT BRAINSTORMING

Although innovation at Whirlpool is an entire management system, the basic currency of innovation is still new ideas. Our firm encourages new ideas from anyone, anywhere and has online forums to track and develop these collaboratively. However, the majority of new ideas come from structured ideation sessions. These sessions (labeled “idea labs”) are far from random brainstorming however. Participants invited to these labs are expected to do significant homework and often post-development as well.

Individuals prepare for an idea lab by bringing with them “discoveries.” These may be new consumer insights, competitive information, or technology developments. These discoveries are not intended to be a new product or business idea, but an insight off which to start building ideas. For example, a general observation (verified by data) might be that “people in nearly all parts of the world are living longer.” A more specific discovery might be that “people in the U.S. and Canada very often eat breakfast while driving.” A competitive discovery might be that “competitor XYZ is adding capacity to its cooking factory.” A general technology insight might be that “resins have become as expensive as steel.”

None of these insights is intended to lead directly to a product innovation, but people bring them as the amino acids of good ideas. Often these insights are “smashed together” in a structured way to produce ideas. Here is an example of three independent discoveries:

- People in nearly all parts of the world are living longer

- Resins have become as expensive as steel

- Consumers find our oven controls confusing to use

Smashed together, they might produce this idea: “let’s design a range with simplified, big buttons and switches that are heavyweight steel and appeals to senior age consumers.”

Often, this idea smashing will produce results that are impractical to the point of silly (“refrigerators for dogs” “one cup dishwasher”) but at this point of ideation we are trying to produce as many ideas as possible, not a single “home run.”

Idea smashing sessions can quickly lead to hundreds of one-off ideas: many silly, but some very intriguing. These single ideas are then grouped into “domains.” A domain is a collection of ideas that begins to define a whole area to explore. For instance, these are one-off opportunities from an idea smashing session:

- A refrigerator with anti-bacterial surfaces

- A dishwasher with a special sanitizing cycle

- A clothes washer with a hypo-allergenic feature

These ideas, perhaps with many others, start to build into a story around what might be called a “health and wellness” domain. The reason we like a set like this is because a “domain” gets us thinking about a whole cadence of innovations, around different products, with clear (potential) consumer benefits. It is well beyond a “single feature” or “single product” invention. The idea of “cadence” is powerful because we prefer to innovate into a theme that provides years of potential subsequent business development.

Even from the early ideation stage, Whirlpool does not favor random brainstorming. Ideation labs are informed by facts (discoveries) that are brought in and used to generate ideas that we might not have thought of before. These ideas can be impractical or even comical, but even those ideas may lead to ones that are more practical. These quickly generated ideas are built (when possible) into broader “domains” to explore. It is this early conversion from “discovery” into “domain” that is not possible with single random ideas. Additionally, the structure of an idea smashing session will always produce hundreds of ideas whenever it is scheduled. There is no waiting for a “eureka” moment from an engineer or businessperson.

A word about participation on ideation labs: diversity is the most crucial component of generating the best ideas and domains. Not just general diversity characteristics, but diversity of job type, company seniority, temperament and so on. Having the broadest mix of diversity at the ideation session is the single most important characteristic to generating the widest set of ideas from which to work. At Whirlpool we have called off or rescheduled sessions when we did not think we had enough broadness of perspective and experience for the group.

BASIC BUSINESS CASE FORMATION: ORGANIZING IDEAS INTO NARRATIVES

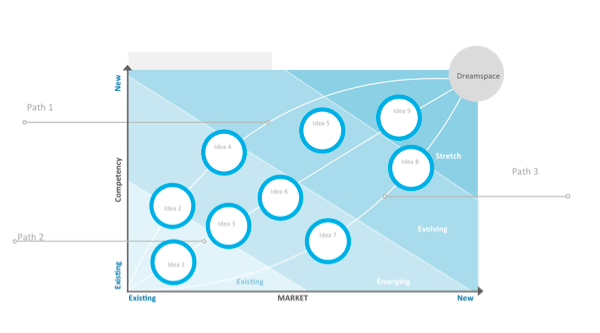

If an idea lab generates an interesting enough domain, the next step is to develop it using a tool and process called a migration path (figure 2). Because Whirlpool core business is consumer durables, bringing new products into the market place often means high capital investment. Therefore, the firm will typically want to size up the potential longevity of its investments. A migration path is where the business of sorting out short term incremental steps from longer term ones is done.

In the hypothetical “health and wellness” domain, short-term opportunities might be to upgrade the protection provided by water filters on our existing refrigerators. Mid-term ones might be to develop appliances with anti-microbial surfaces. Longer term opportunities get more and more speculative – a “whole home sanitizer” for instance. This is still an ideation tool; it may have a number of product ideas that have not even been invented yet. In addition, it has not been thoroughly vetted for its reasonability for technical nor business feasibility. It is simply a way of sorting out the potential domain in terms of its size. The migration path for “health and wellness” would be considerably wider and more open ended than an alternate domain around revolutionizing cook top surfaces.

COMPETITION: FROM IDEAS TO ACTIONS

As domains and migration paths for different ideas get more and more refined, they begin to enter the internal corporate market for resources. All regions in Whirlpool have “innovation boards” (I-boards) or an equivalent group populated by business leaders. These are the gatekeepers of human and dollar capital, and I-boards are where decisions are made about which ideas to develop into working projects. It is at this stage where Whirlpool begins to apply rigorous criteria and measurements to innovative ideas. This is crucial – because innovation ideas developed this far are in competition with each other as well as with “mainstream” project investments.

Whirlpool innovation criteria:

- Unique and compelling solution valued by our customers and aligned to our brands, and…

- Creates sustainable, competitive advantage, and…

- Creates differentiated shareholder value

Each of these criteria may sound generally appropriate, but they also reinforce a very specific point of view about what we believe an innovative business proposition is.

- “Unique and compelling” – means the product, feature or service must be new to the marketplace, or at least new to Whirlpool. Copying another competitor’s product feature is not innovating.

- “Aligned to our brands” – means that the innovation must fit at least one of our brands’ promises. Even if an ideation session generates a fabulous idea for life coaching, or perhaps a military weapon – these would not align with any of our brands nor corporate vision.

- “Valued by our customers” – means that the innovation must be something experienced by the end users of our products or services. Ergo, the most “innovative” idea for cost reduction or better supply structure or some other non-customer facing improvement are de facto not innovation projects.

- “Sustainable, competitive advantage” – means that the idea must make use of patents, technology, distribution, brand strengths, corporate scale, or some unique company advantage such that our competitors cannot effectively copy the innovation for at least two years.

- “Differentiated shareholder value” means that the innovation idea must show a feasible business case that returns will be meaningfully higher than the current returns in that particular product segment. This is most typically achieved via a price premium that we predict our customers will pay for the innovation. The reasoning is the belief that customers pay for “real” innovation. If higher pricing is not expected, then the idea is not in fact innovation (also reinforces the criteria “valued by our customers” above).

Because our core business is household appliances we work in a very mature and very saturated market for most parts of the world. It is not easy to come up with business cases that meet these very stringent criteria. The byproduct is that more and more of our successful innovation cases emerge from opportunities that either expand our core or go beyond it. Most of all, the process of prioritizing which innovation propositions we resource is not anecdotal or opinion driven – there is structure and process to drive our decisions.

EXPERIMENTATION AND COMMERCIALIZATION

For those projects that pass our concise but stringent criteria, Whirlpool assigns resources to develop these cases further. If the cases are new product innovation they are resourced in a similar fashion as “non-innovation” developments are – with team members selected from marketing, technology, finance and so forth. They are run through our primary development process “Concept to Consumer” (C2C), with traditional types of tollgates (concept lockdown, investment decision, product launch, etc). Depending on the “intensity” of the innovation, the project may call for more extensive market research, prototyping or other basic market experimentation than core projects would.

For non-core projects (in Whirlpool’s case this might be ventures into services, non-durables, etc) the resource profile may be very different based on the type of opportunity at hand. Even for non-core work, Whirlpool will conduct relatively standardized tollgates at key points in the product or service development cycle. In either case however, officially approved innovation projects are specially tagged for reporting purposes.

FROM MICRO TO MACRO

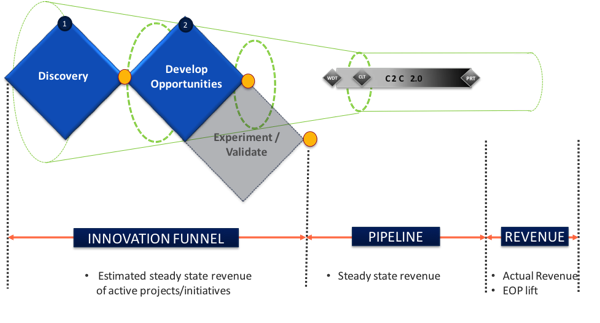

Nearly all innovation activity – from idea to scale-up – is logged into Whirlpool’s Innovation Pipeline (I-pipe). The I-pipe is a straightforward data collection tool that allows employees to look up details of any particular active innovation idea. Whirlpool also keeps track of cancelled and shelved projects – and the majority of ideas are in fact shelved at some point.

Additionally, the I-pipe also provides an aggregate view of innovation activity. Employees can quickly see how many active projects there are, in which regions, by what product categories and so forth. This is important as we move from the “bottom’s up” innovation world (idea generation, development and commercialization) to the “top down” goal setting and strategic view.

The effort and expense of idea generation, business development and commercialization of innovations at Whirlpool is not conducted just because it is interesting. The company has ambitious goals to drive profitable growth within and beyond its historical core businesses. To that end, the data in the I-pipe shows not only current results from innovation activities, but calculates the reasonable amount of revenues and earnings should expect several years into the future based on the innovation activities under development today. Although this type of modeling is in use in some industries like pharmaceuticals, we believe it to be unique in the world of consumer durables.

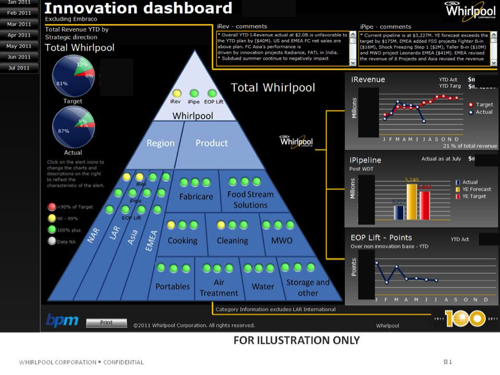

There are rarely specialized forums or meetings to call out innovation performance. Innovation instead is integrated into most aspects of ongoing financial reporting, such as monthly operational review, as well as more complex business planning cycles. Key metrics such as current year revenue, EOP lift and future revenues are discussed as part of ongoing business, not as a “special topic.”

Because of the maturity, saturation and scale of the world-wide white goods industry, Whirlpool by default must reach its growth and margin long range targets through ever higher investment in innovation and non-core business opportunities. Using the data from the I-pipe, senior leaders can get up to date on not just current year performance and future year trends, but also on other portfolio-level indicators such as which regions or products are driving the most innovation.

When thinking through the discipline in place for creating basic consumer ideas, all the way to setting long range performance targets for the company, Whirlpool’s unique innovation is to not drive any particular “innovation” (small-i), but to craft a system that continually drives “Innovation” (big-I). Because we have structure for “producing” ideas, and then prioritizing ideas, and then commercializing ideas, we have a reasonably reliable way of looking several years out and understanding what our innovation efforts should bring us in growth and earnings. Matching that data against our strategic objectives of what we want to drive in growth and earnings is a very powerful way to manage our decisions, resources, and “big bets” we will make in the market place.

There are three major challenges to maintaining an effective innovation environment:

- Core versus not

- Simplicity versus sophistication

- “But I’m a special case”

None of these has intrinsic solutions, because any of these tensions taken to one extreme or the other they become counterproductive. Instead, we manage the tensions.

- Core versus not

Even though we know in aggregate that more and more of our innovations need to come from business areas outside white goods, the majority of our innovation work still comes from our core business. It is where our history and expertise are for our business and technology employees. It is also where some senior decision makers are more comfortable when making prioritization decisions.

To counteract this tendency, we are deliberately making ourselves aware of it:

- Our regions have targets to establish “XYZ” percent growth from non-core businesses each year

- A substantial amount of capital funds are held centrally each year, so that we can be flexible in resourcing unexpected innovation opportunities coming from anywhere around the world

- The top innovation prospects from each business segment (even if relatively small or early in development) are monitored on monthly dashboards reviewed by our executive committee

- Simplicity versus sophistication

For nearly a decade, Whirlpool management has seen that innovation must be a system, not just a list of targets or a particular ideation methodology. However, there is a never-ending discussion about adding more structure and metrics sophistication versus process simplification. Too many measurements and steps drain excitement and slow down development. However, oversimplifying the process leads to less visibility, and potentially weaker ideas (less vetting). Our coping mechanism for this is a sort of 70/30 split:

- Seventy percent of our innovation mechanisms are globally standardized: elements such as strict adherence to innovation definition, performance metrics, tollgates, and executive review. These elements are embedded with very little change over time, and understood around the world.

- Thirty percent can vary over time or within region. Elements like prioritizing ideas, experimentation techniques, ideation tools and how teams are assigned to projects. These are the practices which may float, or become more customized to the local business and may vary depending upon organizational structure, talent and resources.

- “But I’m a special case”

People generally support the idea of process standardization right up until the moment when it is inconvenient for them personally. No matter the process, there is a human tendency to try to get around it. Our coping mechanism is again two-fold: First, no innovation projects “get around” the process. They are all vetted against the same innovation criteria, they all have standard financial modeling, and all must compete for resources openly (no “back-dooring” of projects). Secondly, we attempt to make the process itself engaging and easy to learn. A lot of the resistance to follow a process breaks down once people learn that the process is not scary or especially bureaucratic. One example of making this easy: the most senior leader in the most senior decision making forum “signs off” on whether innovation criteria are met. The team proposing the idea makes their case on one standard page, and the senior leader makes the decision. He or she must also be accountable and ready to defend that decision to their peers. This frees up resources for innovating instead of trying to make special cases.

The primary benefit of innovation is value creation. Prior to starting our innovation embedment approach (1990s), average sales values were declining approximately 2% per year. From the early 2000s to present (since we started our new innovation approach), there has been a nearly precise reversal of that trend, with prices climbing on average by 2% in aggregate. This was achieved by bringing new products and investing in new features consumers were willing to pay for. Another important contribution to this came from our efforts outside the core and the investments in adjacent businesses.

Just over a decade ago it would have been nearly comical to associate leading edge industrial design, sophisticated brand management and business innovation with an appliance company. However, recognition from Fortune Magazine, the Edison awards and a number of other independent voices validate that this is very relevant for Whirlpool and white goods today.

Whirlpool relies on different layers of metrics, depending on where we are looking in the innovation process. At the project level basic financial returns are very important (NPV, IRR, payback), as is the potential size of revenue gain. The ability of an innovation project to generate “lift” (EOP percent above the current performance) is also crucial. If projects do not show a reasonable and clear path to profitable growth they are de facto not an innovation.

At a top down view, more aggregate metrics become important: Current revenue and product margins across all innovation efforts are very important; as is the value in revenue and earnings of future projects (the innovation pipeline). Other more systemic metrics are measured as well – total number of active innovation ideas, average speed from concept to consumer, and percent of revenue coming from innovation.

At Whirlpool we err slightly on the side of “many metrics” versus “few metrics.” While it is very tempting to use just one or two targeted metrics (e.g. “drive growth!” or “work only the highest NPV projects!”), we have found this to lead to very suboptimal behaviors (such as potentially driving growth that is not attractively profitable, or only picking projects which have longest payback and highest risks). Looking across a number of metrics tends to ensure we have a balanced and informed view of what we are trying to accomplish.

- Innovation really can be systematized as a core competency. Treating it as a program will yield “programmatic results” at best. Treating it as a separate skunk works or think tank will yield less still. But turning innovation into a management system requires vision, perseverance and purpose.

- Unsurprisingly, transformative actions such as embedding innovation as a core competency must be driven from the top, and must be continuously driven.

- Expect to continually reinvest, particularly in human capital, to drive innovation. Personnel turn over, organizations restructure, and short-term priorities battle with longer term ones; our innovation system (just like a computer operating system) requires updates, retraining and tuning.

- No single metric should overtake an innovation effort.

- If every single one of your innovation ideas is successful, you are not defining innovation correctly. Most innovations are not successful.

- Do not be mad when most of your innovation ideas are not successful. Learning really is worth something! Whirlpool keeps meticulous record of all of its failed innovation ideas. They feed new ideas, and they remind us of what did not work before.

- To the extent possible, make innovation a fun activity to engage in. Draw in people from all parts of the business. Diverse groups always come up with better ideas than narrow ones.

Nancy Tennant, Jacqui Winship, Moises Norena, JD Rapp, Chris Rocke

You need to register in order to submit a comment.