M-Prize Winner

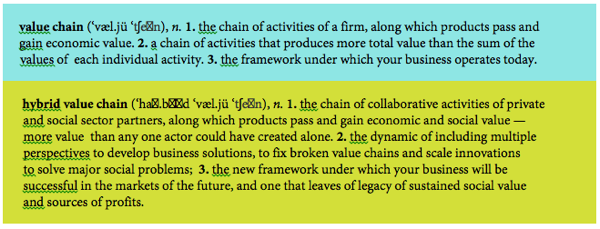

This story is one of ten winning entries in the Long-Term Capitalism Challenge, the third and final leg of the Harvard Business Review / McKinsey M Prize for Management Innovation.

Story:

Ashoka’s Hybrid Value Chain: Revving the Engine of Sustained Global Prosperity and Social Value

Governments and philanthropy combined don’t have enough resources to serve citizens’ needs. Private sector market forces are large enough, but business is stuck, narrowly focused on shareholder profits. The citizen sector has half of the facts business needs to innovate and get unstuck, but the two sectors don’t communicate. Social-entrepreneurs have the skills of both, but their innovations must scale to have major impact. All need a new inclusive, collaborative framework to compete successfully -- and to sustain capitalism well into the future. Spreading that new framework to reach its global tipping point is a mindset and management challenge. Enter: Ashoka’s Hybrid Value Chain (HVC). [1]

Bill Drayton created Ashoka in 1981 with a clear strategy: the world’s most pressing problems are best addressed by a great idea in the hands of a social entrepreneur: a hybrid professional with the skills, savvy and relentless drive of business innovators and the passion and values of leaders who care about purpose, creating lasting value for the world. [2] Today Ashoka is a network of 3,000 social entrepreneurs developing innovative solutions in over 80 countries. Its vision: A world in which everyone is a changemaker, able to respond effectively to life’s challenges, with the confidence and skills to seize opportunities and to find the resources, teams and solutions to drive positive change.

Ashoka’s Full Economic Citizenship (FEC) is key to reach that vision and take social impact to a whole new scale with strong market incentives and forces. FEC creates new frameworks and forges the connections and opportunities for all everywhere to participate in the formal market economy -- as empowered consumers and successful producers, co-creating with business the products and services they buy, able to grow their savings, credit, skills and assets, and leverage them to generate prosperity for themselves, their family, community and nation. In so doing, they are irreversibly transformed to become changemakers, continuing to contribute to business and social growth. Given that over two-thirds of the world’s population do not have these opportunities, doing this is no small feat.

After decades and hundreds of Ashoka Fellows working across the globe to innovate solutions to generate new jobs and income and including citizens, communities and social value, their ground-breaking innovations, while brilliant and effective locally, hit the wall of global scale. Business as usual, or value chains created a century ago for whole industries, weren’t adapting fast enough to spread new solutions for new problems or new markets. As we reflected on this pattern, we asked: “At other times in history, entrepreneurs in the context of capitalism had innovated breathtaking changes that, when their value was evident for business and consumers, grew to become a new reality. Why wasn’t that happening now? What was preventing the disruptive innovations of social entrepreneurs from being embraced by mainstream businesses and growing to scale?”

Why wasn’t capitalism innovating successfully? Trigger one: The root cause is a fundamental breakdown of how society and businesses are structured, a change that in our generation is accelerating exponentially. For millennia, the world operated under an archetype of hierarchy, power in the hands of a few who made the rules and enforced them. Henry Ford’s assembly line production system was a then-modern restatement of this same paradigm. While game-changing in its time, it no longer serves ours. Unprecedented access to knowledge, science, technology, information and instant communication open people’s minds to new possibilities and speed the rate of change around the globe as never before.

Symptoms of the old archetype’s disintegration are all around us: economic bubbles bursting industry-wide (tech in 2000, housing/finance in 2007); unemployment, fear and famine growing; dictators toppled by social-media-led popular movements; civilian “occupiers” challenging the 1% to connect with the 99%; stalwart companies vanishing; the gap between rich and poor widening, just to name a few. While these unnerving dislocations appear chaotic, they are all symptoms that the old archetype is failing. Government, charity and business models are stuck, the old rules and patterns no longer working. They beg for a new framework to emerge that makes sense for the future.

Trigger two: the global growth of social entrepreneurs. Turning obstacles into opportunities, they cross sectors as if there were no walls or border patrols. They believe scarcity can be turned into abundance, and the only magic needed is to stimulate human innovation. They know how to access it: Pinpoint where value chains are broken and where new opportunities have emerged. Identify all the major, diverse players with the need, skills and passion to fix the breaks, grab opportunities and invent better solutions. Forge alliances among these stakeholders to put their knowledge and expertise on the table and co-create innovations. Together test and refine innovations on the ground until products, services, cost, distribution are right. Attract bigger players who can inject the capital, scale and infrastructure to make an industry-wide ecosystem that spreads and sustains innovations grow to scale. The result is better than any one could accomplish alone.

That obvious, you ask? Then why don’t more businesses do it? Because they don’t know how. Trigger three: Business frameworks themselves are not suited for the future. Silos in sectors and industries have narrowed function and experience so that creative sparks that ignite “aha’ moments are in short supply. Many businesses have pushed up against the limits of their traditional solutions and markets. They cannot see how to expand further. Producing and selling at high profit margins worked well when the ideal customer was the upper and middle classes. But with these markets nearly saturated, where will sources of profits and growth be found?

One answer came from Milton Friedman, who wrote “The only social responsibility of business is to create profits,” launching more than four decades of economists and management consultants teaching business leaders to maximize shareholder satisfaction as the best solution for wealth creation not hampered by saturated markets. [3] Trigger four: Narrow focus on short-term profits has dominated business management for the past 40 years. Business even more remote and isolated from larger social good. Look where that has gotten us.

Trigger five was first voiced by the late C.K. Prahalad, who described a new frontier for corporate growth: the four billion people – two-thirds of the planet’s population – largely excluded from formal markets and invisible to global businesses. Prahalad influenced a whole generation of business and social leaders with the promise of untapped multi-billion dollar markets and billions of underserved consumers. [4] Prahalad invited corporations to explore the base of the pyramid (BoP), and many followed his suggestion. [5] But early initial successes faded, enthusiasm waned as profits at scale remained elusive. [6] Systemic or paradigm-shifting new business frameworks did not emerged to take advantage of the “wealth of the poor,” the “blow-back value” of innovations created in emerging economies, or enable businesses to engage effectively with their potential new customers or vendors.

Where did these triggers leave us? With the certainty that we need to develop, refine and spread globally new, inclusive business frameworks. Ones based on a new archetype: Long-term and sustainable success is based on triggering unprecedented innovations which arise when businesses citizen sectors collaborate.

THE INNOVATION: HYBRID VALUE CHAIN (HVC)

The real game changer is the framework. Just as Ashoka earlier hacked “business entrepreneur” and made a hybrid – the social entrepreneur, FEC hacked a respected business model, “value chain” to create the Hybrid Value Chain, whose structure forges collaboration to deliver private profit and social value, becoming the renewable source of energy for innovation and the new paradigm for inclusive and sustainable capitalism. [7]

HVC is built on the equally important (and different) strengths from the private business and citizen sectors. It respects the legitimate goals of business to generate profits, as well as private access capital, ability to manufacture and distribute at scale and specialized talents to invent new products leading to better goods and services available in the market.

HVC respects citizens’ value in these processes as equal stakeholders. Their needs and insights into their communities and cultures are essential raw materials to design appropriate products and services; develop affordable quality; produce more accurate and useful market data; and often do a better job of marketing and sales than companies’ staffs. When they perform these services for businesses, they receive income.

HVC is by nature a holistic and iterative process: not based on one-off transactions, short-term gains or individual deals, but an ongoing collaboration based on learning from different perspectives, increased innovation, products and services that reflect manufacturer and consumer and revenues that will transform a sector’s development for decades. It is also about creating transparent and competitive markets so consumers and producers benefit not just from having access, but from better prices, products and services.

HVC is not limited to serving low-income populations. Innovations in sectors often come from the citizen sector’s keen awareness of unmet needs: Banks, for example, did not develop microfinance institutions or new loan products – even though billions of new customers were ready to sign up. Solutions to the issues of Internet privacy are not flowing from major digital companies, but rather from civil society. And the glaringly broken U.S. health care value chain is not being fixed by the medical profession or private insurance companies. If solutions come, they will most likely involve the insights and ingenuity of multiple stakeholders to get the fix right.

HVC systematically weaves the two parallel, sometimes intertwined, and always communicating paths of business and social entrepreneurs – like the double helix of DNA – to sustain a dynamic flow of energy and creativity that produces innovation, economic inclusion AND wealth creation for all. See the graphic below summarizing the assets and benefits all the stakeholders bring to and take away when an HVC process helps them collaborate over time.

HOW DO YOU KNOW AN HVC WHEN YOU SEE ONE?

If you think an HVC might be an appropriate framework for a sustainable solution, what must it include to be an HVC (and not another kind of innovative business model)? As we define them, HVCs have several must-have core criteria: [8]

- PRODUCE SOCIAL BENEFIT. Will the HVC solution have meaningful impact on an intractable social problem affecting millions of people?

- OPPORTUNITY FOR NEW PRIVATE INVESTMENTS AND PROFITS. Will it succeed relying on market forces? Is the market large enough so new revenue streams created justify the investment?

- CITIZEN PARTNERS. Are there trusted citizen organizations who can link communities and individuals to the HVC process and help unleash new and untapped market demand and resources?

- CORPORATE PARTNERS. Are there companies with the motivation, resources and ability to execute a collaborative HVC solution?

- BUSINESS MODEL: CONSUMERS MUST PAY FOR GOODS AND SERVCES. HVCs are not charity or CSR projects. They cannot rely for success on recurring subsidies. Sustainability and scalability must rest on profitability.

- SCALABLE SOLUTIONS AND GROWTH POTENTIAL. Will the HVC solution impact on the company’s bottom line, change industry practices and improve millions of lives? Can it deliver its solutions elsewhere with similar needs?

- COLLABORATIVE INNOVATION CREATES NEW VALUE: Does the HVC add value? Does it actually expand the market pie so profits are not “shared” but there are more to go around, based on the input of all? [9]

HVC Results: Companies that work with and learn from the citizen sector discover endless new insights that ignite future innovations, inventions and processes, resulting in added value, sustainable ways of succeeding in new markets, and new communication channels that continue to align growth with markets’ precise needs and assets. Using HVC, companies reach large new markets faster, better and more cheaply. They gain competitive advantages and first-mover benefits.

Citizen and community organizations gain skills to address the systemic causes of problems. By allying with companies, they have the financial and infrastructure heft to address these systemic changes. They therefore increase their value to their clients.

Clients participating directly in HVCs move from being stymied victims of poverty or informal and invisible members of society to a level of skill, confidence and efficacy that lasts for the rest of their lives, enabling them to continue the journey to full economic citizenship, to have the self-esteem and skills to provide for their families’ future. Together – businesses, citizens and their organizations -- they can promote changes as powerful and widespread as those produced by the Industrial Revolution.

AFTER THE HVC FRAMEWORK HACK? APPLY, REFINE and SCALE

We knew “what” was needed: Use the HVC framework to form social-business alliances to capture multi-stakeholder information. Tear down the walls and silos that separate sectors. Establish patterns of open communication and collaborative problem-solving. Use Insights from diverse players to catalyze innovation. Building new management practices based on these diverse perspectives. See mindset changes evolve in both corporate and citizen sector leaders to respect, trust and collaborate effectively together.

A different way to view wealth creation and social value: Not as “either-or’s,” (which are dichotomies that served the old political and business paradigm), but as “and’s” (the inclusivity that global diversity requires for future success). Competition and collaboration. Long-term social value and private profits. Citizens and for-profits. Social and business entrepreneurs. Quality and affordability. Private profit and full economic citizenship..

We needed to learn new HVC “how to’s”: How to forge working relationships between the citizen and business sectors? To agree on core values and objectives? To create a shared roadmap? To put their knowledge and questions on the table? For citizen organizations to be comfortable about the notion of helping to deliver private profits and adept with managing budgets, timelines, increasing scale? For business leaders to see citizens as a fountain of essential ideas for products and services and skills for marketing and sales.

Ashoka FEC launched in-depth HVC applications in affordable housing in India, Brazil, and Colombia, rolled up our sleeves and got into the weeds of how HVC works in practice. We also continued to learn from the growing examples of Ashoka Fellows’ collaborative business-social alliances in other major sectors – and to keep abreast of others doing similar work to ours -- to ensure HVC had legs sturdy enough to be useful at scale. [10]

In late 2010, the Harvard Business Review published our preliminary article on the HVC framework. [11] An outpouring of corporate and social entrepreneurial responses told us we’d struck a deep need and sensitive nerve in both the corporate and social sectors.

Since the initial publication, we continue to develop the applications, learning new lessons and having “aha” insights that speak to questions of achieving global scale and changing mindsets with a speed that business and social innovation need to succeed. In the LESSONS section below, we’ll expand on these. But first, let’s look at an example of HVC applied to the affordable housing crisis in India.

ASHOKA HOUSING FOR ALL (HFA) INDIA. We chose housing as a sector that grossly underserved market demand and was itself floundering. HVC framework’s criteria guided our actions.

Globally, over 1.6 billion people live in shelters that do not meet even minimum UN levels of safety and hygiene. (Lots of social benefit needed! Met our criteria of scale.) That number will triple by 2030. (Sustained growth potential, decades of multi-million dollar business opportunities!). In India alone, the affordable housing deficit is more than 26 million new homes and 45 million self-built homes needing improvements. This equates to a potential new home housing market of US $250 billion, and more than double that when the home improvements market value is added. (Potential for sustained new profit and social benefits!)

There were private real estate agents and builders with skills and interest to handle the construction need. (Corporate partners possible.) There were also several large, trusted citizen sector organizations who served this very same BoP population (Citizen sector partners available).

The criterion (#5 above) – customers willing and able to pay—was not a given when we began. After all, if families had money to buy a new home, why didn’t the private realtors already have them in their portfolios? To get the answer, we looked more closely at the market and our target clients, and we understood that there was a Pyramid within the Pyramid. That is, not all the BoP is equally poor. [12]

For the very bottom segment, government support, subsidies and assistance are needed and appropriate for its widows, single parents with many small children, handicapped, elderly, sick, or newly arrived from the countryside needing a transitional period to adjust to urban life. This segment was not ready for market solutions or HVC.

For the very bottom segment, government support, subsidies and assistance are needed and appropriate for its widows, single parents with many small children, handicapped, elderly, sick, or newly arrived from the countryside needing a transitional period to adjust to urban life. This segment was not ready for market solutions or HVC. But the two top segments of the BoP– those who had built their own dwellings and needed improvements, and those seeking new housing, were working or owned small businesses. They included families making between US$250 and US$500 per month, who can afford new homes if the cost did not exceed US$20,000 per unit.

So why did they not have home equity loans to make improvements or get mortgages to buy a new home? Because these hard-working families lived in an “informal” economy. Their employment, rent and purchases are cash-only transactions, even if they are steady and continual. They have no pay stubs, no tax returns, no receipts for expenses, no paperwork to say they’d built their homes or paid rent for years – in sum, no way to qualify for the few loans that might be available to them. Our challenge in order to make the HVC work was to fix this roadblock: increase access to credit.

At this point, a private builder or realtor would have walked away from this untapped opportunity. Neither believed they had the skills, time or contacts to solve this barrier. But we knew we could find or innovate what was needed.

We turned in two directions for solutions: First, we asked our citizen sector partners – SEWA and Saath – to help working families document their income, what they currently spent for housing, and give them financial family planning skills to start a routine of saving each week -- to have enough to deposit savings in a bank and, with paperwork, qualify for credit and have a down payment ready.

Second, we sought banks to develop appropriate low-income mortgage or home equity products for this population. It was too far a stretch for traditional banks. They just couldn’t see how to do it. So we turned to microfinance institutions who had relationships with many of these clients for other kinds of loans. They had demonstrated experience which of these BoP clients faithfully repaid loans. All we had to do, we thought, was inform them specifically about new home loans (longer term, lower interest rates, collateral, etc.).

But another barrier arose. Their own good processes for establishing BoP clients’ credit-worthiness were very time-consuming and costly, pricing a home loan out of reach for potential home buyers. Once more we turned to citizen organization partners for a business solution: pre-qualify local residents for microcredit loans. Their costs were lower, their services faster to aggregate and process families for loan pre-approval. Again, the citizen sector helped the private microfinance sector gain access new clients, which in turn enabled builders and realtors to profit as well.

But the builders were not totally convinced they’d be successful. Relying on official government census and commercial housing data, the numbers did not seem to justify their risk and investment. Several shared experiences of building new housing, only to have units go unsold, even though they were a significant quality upgrade from the slums where customers were then living. This critical roadblock led us to another investigation of the market.

Ashoka HFA India developed its own survey to measure household size, needs and preferences in more detail. Our partner citizen organizations trained slum residents to go door to door and ask their neighbors the questions on the housing surveys. At least more honest data would emerge. We developed ways to collect, analyze and quickly monitor and share data collected: an electronic template of the questionnaire and a mobile app so that the interviewers could prompt and input all the answers on a simple hand-held digital tablet. (While there, they also took and attached a cell phone photo of the head of household in front of his current address for later verification of identity and residence required for loan approvals.)

Data was then sent electronically to the Ashoka HFA India office, where trained staff used specially designed software to sort the data by different aspects: income, size of family, ages, special requirements for space, (e.g., parking a rickshaw, a room or workshop for a home business), proximity to work or transportation, etc. Once consolidated, real-time accurate data were shared with realtors. When we and they compared Ashoka HFA India data to the official ones, the results were impactful. By pinpointing specific housing consumer requirements, size of market demand and ability to pay -- a major private builder changed his mind and agreed to build.

It was citizen-collected data, and simple technology that social entrepreneurs adapted, that provided more relevance and value to business decisions of private corporations. Citizens got paid for their time, they learned a lot about their community and the business model of housing. They all learned how to use mobile tablets quickly and used them and their cell phones’ GPS and cameras to record and transmit all documentation necessary.

As the Ashoka HFA India work continued, new challenges and opportunities arose. For example, even after we had lined up the necessary components to begin building, other private builders were not convinced they would succeed. Traditional marketing had not been a smashing success in earlier private projects for slum dwellers. We wanted to ensure our results would reward the trust and risk the builder had taken.

We did more research: Builders shared his marketing materials and process with us. We shared these with our citizen partners and asked for feedback. They tested it with their clients. We quickly understood these materials, marketing strategies and the well-dressed, briefcase-carrying professionals who did the earlier marketing did not inspire confidence in potential clients. This was the weak link in the value chain the companies never saw or fixed. We developed a new system to raise awareness in targeted communities at large events where clients normally gathered; we trained and paid neighbors to explain the new project in smaller groups. Citizen marketers went back to families who expressed interest and explained each step of the process, and linked them to the citizen organizations who would follow up on all. Deadlines for loan pre-approvals were completed in record time. Citizen partners helped get customers’ relatives jobs on the construction site, and ferried housewives to the first units available to see how it all looked.

The result was 100% sales success in record time. It’s not rocket science. It is the HVC framework in the hands of social and business entrepreneurs communicating, innovating, refining that make it work.

HVC at the Intrapreneur Corporate Level. Other actors (experts, policymakers, government officials, university researchers etc.) play valuable roles in an HVC framework. They can also use HVC as intrapreneurs to build a “changemaker” campus, city or corporation. [13] An example of the latter came early in Ashoka HFA India when Dow Corning asked us to host a group of their engineers and product developers, sent through their Citizen Service Corps. Chip Reeves, VP for Discovery and New Business Development, describes his multiple management reasons for sending his employees who are the core of new product development for the next two decades at Dow Corning for a month to far-flung places. He writes, “I wondered…

what would happen if major global companies sent their employees to work with people in emerging economies for weeks at a time to get to know their cultures, needs and daily patterns of life? Not as "poverty tourism," but rather part of a strategy to have them see with the openness of a child all that is different, all that is happening, and all that is needed in their lives. And then to think how that translates to product innovations.

For two years now, Dow Corning has operated a program called our Citizen Service Corps. Employees volunteer their time, but we pay their expenses, to go to countries where help is needed, and where new markets exist. Our mission: to DISCOVER, SERVE and INNOVATE.

…Building on the experience of major design firms, we have learned how to have the "EYES of a beginner" -- how to put aside our biases and observe how people address problems and issues in everyday life. The “EARS” session practices how to ask effective questions to draw out key insights, information and priorities. In the final session, “MIND,” we model how to think about new business opportunities through the lens of a micro-entrepreneur: Is there a compelling need that we can answer in a way that creates value for us and for others to sustain a new business?

…The Citizen Service Corps…alumni have brought back and shared so much from their work with entrepreneurs in the field, and the results continue to pay dividends. The organizations and their clients report tangible benefits from our team's contributions. The employees have become stronger leaders, their new skills and insights not wearing off over time. And our company has sharper focus on areas of need and opportunity in new markets. This is a scenario for spurring economic development, deeper human connections and a better future. [14]

Reeves’ ability within Dow Corning’s large corporate context to see an inclusive way to spur innovation is critical for his corporation’s staying a step ahead of their competitors in new product and service development and to attract and retain the best and brightest talent to work for them. Reeves is not alone. This HVC values come from the very top of the company. Here’s what then-CEO and now Board Chair, Stephanie A. Burn, wrote Ashoka FEC soon after she read our HVC article in the Harvard Business Review:

…[Working] with Ashoka’s Change Leader of "Housing for All" in India… Our team put Six-Sigma thinking to work. With Ashoka, we created standards for including renewable energy and other environmentally sound practices in the production of affordable dwellings that accommodate the preferences of customers.

For our employees, the learning was extremely valuable. Immersing themselves in the Bangalore environment – even for just one month – stimulated understanding I doubt we could have obtained any other way. This intimate contact with the realities of the developing world generated sensitivity to the challenges and produced ideas for further examination in arenas important to Dow Corning's business, including sustainable housing construction, energy, transportation and personal care.

The exercise also was a journey of personal and professional discovery for our employees that became a path to appreciation of the impressive resilience and entrepreneurship of the men and women they encountered. We've gained a new appreciation for a whole new world of innovation for us to explore.

In fact, the learning was so valuable, Dow Corning is sending a team back this year to work with Ashoka HFA India specifically to co-develop another bold innovation: devising India’s first national set of affordable housing standards. Such standards are especially critical to grow this sector to scale in a country as large as India. With millions of homes to be built and improved, standards create a shared, transparent vision and set of expectations, attracting new stakeholders to the sector. Ashoka HFA India convinced an internationally recognized leader in technical standards and certification, TUV Rheinland, to lead the effort, and with them, developed an HVC process including citizens, builders, architects, cement suppliers, electricians, energy consultants and Dow Corning experts to craft this completely unique way to measure, incentivize and monitor quality at low cost.

Thinking ahead of enforcement, policy support and scale, they invited municipal leaders and policymakers to attend workshops. Government had not been a driving force in the Ashoka HFA India model. Yet ratification, acceptance and enforcement are needed for standards to work. At these meetings, they won the endorsement of a top municipal official to champion the implementation of the standards when ready. [15]

We cannot overstate what a seismic change this is. A larger ecosystem of supporters with more impact is forming. A major global corporation found so much value in their time with Ashoka HFA India that they are investing more of it to take it to the next level – not out of charity, but in everyone’s self-interest. A top government official will take on an entrenched bureaucracy to fight for national affordable housing standards because she has seen the future benefits for her country. The HVC framework – and the alchemy of trust and problem-solving by multi-stakeholders -- is working.

STORY TIMELINE:

2003 FEC begins at Ashoka

2005 First Ashoka Housing for All application starts in Colombia; a year later one starts in Brazil. [16]

2008 Ashoka HFA India begins, engages and convenes core HVC partners, building a functioning HVC.

2009 Ashoka HFA India built, got loans approved and sold new housing for 675 slum families in one city India, with microfinance agencies added.

2010 Expanded to 3 more cities, more financial partners, more private builders and realtors added.

2011 4,000 new homes in 5 cities in the pipeline. Developed a process to attract, select and train HVC entrepreneurs to expand the model to fifteen cities throughout India to build or pre-qualify for home loans 35,000 households between 2012 and 2014.

2012 Plans for achieving global scale are developed. These start now and continue over the next three to five years. See below in our LESSONS section the details of our next phase spread HVC to enable global scale.

This is not the end of the story. Major global corporations such as CEMEX, Holcim, LaFarge, Dow Corning and others have reflected on how much they did not know about both their market and its untapped opportunities. They’ve had repeated “Aha” moments, realizing that their company’s immense expertise was only one piece of a larger puzzle.

At a Global Summit of Housing Entrepreneurs organized by Ashoka FEC to bring multi-sector leaders together to share lessons and coalesce to address structural barriers to scale (e.g., land rights, infrastructure, loan fund guarantees), this wrap-up insight by Israel Moreno, former head of CEMEX’s global affordable housing initiative called Patrimonio Hoy, summed up the conclusion of many:

We [housing stakeholders] have been working by ourselves for far too long…we each have only a part of the solution. This Summit is challenging us to find a better way of working together so that we can address the incredible need for sustainable housing around the world. [17]

Moreno’s conclusion about the sector he knows best resonates throughout FEC’s work in many other sectors. HVC values, methodology and tools have crossed multiple sectors and multiple geographies with vastly different cultures. Although the specifics necessarily adapt to fit local and national needs, the core framework is what keeps it moving ever more toward inclusion, trust, collaboration, open information and a multiple bottom line for all: people-profits-society-planet. [18]

Since writing about HVC in the Harvard Business Review, we have had our own “Aha” moments about the strength of the framework and what needs to be done to get it to evolve from a hack or innovation to mainstreamed business and common sense.

We think these lessons fall roughly into three groups:

- When does it make sense for a corporation to partner to create an HVC?

- What guidance is there for those who want to build HVCs?

- What is needed for HVCs to reach scale and full global market potential?

1. When does it make sense for a corporation to partner to create an HVC

A short answer is: when the seven must-have core criteria stated earlier exist. Think about it. Each of those core criteria are key to the HVC producing new dialogue between the social and business sectors that spur unprecedented innovation and produce enough ROI for all for the time, personnel and money invested. So unless there is a really good reason or way to cover for no more than two missing elements, the idea is probably not ripe for creating an HVC. [19]

Not all underserved markets need to be developed through HVCs. A prime example are cell phones. The cost per unit was not prohibitive, the value almost immediately obvious, the distribution channels flexible. Companies did not need any help from citizen sector organizations to achieve remarkably fast and large market penetration. A similar situation is the case of most consumer goods that can be found in every small shop around the world, including remote locations. Somehow these get distributed, paid for and sold without any help from an HVC.

HVCs make sense with “high-price ticket items” that need credit or insurance products to enable a purchase (a house, major surgery, an irrigation system for the farm, etc.) and/or a service that requires significant consumer education and awareness to create real market demand (even if “need” is obvious) to become viable. Take the case of innovative and relatively low-cost drip irrigation systems as an example. Companies manufacturing and selling them seemed correct when they concluded that small farmers are not a viable market for their products and services. They were too scattered and remote to find and serve; they had no savings or credit to purchase a new system; and they were not motivated sufficiently to get credit or buy one because their meager productivity meant small orders from local small buyers – so why bother with all that was necessary to get better systems?

But an HVC alliance turned this stalemate around. Step one was to show farmers purchase order commitments from bigger buyers IF they could improve their productivity and quality. Second, these orders were based on larger quantities than any one farmer could produce, so they were convinced when the citizen organization offered to help them form larger coops and selling groups, aggregating supply to meet the scale needed. Now the farmers became interested in how to fulfill the orders and grow their incomes. They changed their minds, talked with local microfinance companies recommended by trusted sources, who offered loans for irrigation systems to the farmers who sold to the big buyer. Local universities and agricultural experts helped with technical assistance on how best to use the systems and other hints for healthier crops – and the HVC resulted in profits to all. Just as in the housing example from India, no one company wanted to go through these many steps – they simply sold elsewhere and left potential profits and the farmers in limbo. Now several are vying for this new market segment.

For some large social problems and possible product solutions, HVCs may not be right because the “potential consumers” are the poorest of the poor and hence would not soon be able to pay for products and services without ongoing subsidies. If you recall the Pyramid within the Pyramid from our Ashoka HFA India market analysis, there were three levels of BoP. The lowest – comprised of the very elderly, handicapped, single mothers with many young children or new migrants to urban areas with no savings and no skills to get work – really need charitable and public support. Subsidies for housing are appropriate for them (for the new migrants, this may be temporary, until they adjust to city life and find training or employment, but for others, it is the appropriate role of charity and government to help society’s most vulnerable). By knowing what is NOT appropriate for market forces and HVC models, charity and government can make better investments with their funds (because it focuses on only a defined segment of a huge problem, and they can make a dent in that segment). At the same time, HVCs and corporations can target the market segments where savings, credit, increased employment opportunities and short-term skill-building would transform “beneficiaries” into real consumers able to participate in a market economy to the benefit of all.

There is also a threshold of readiness to become an HVC partner. The corporation should have experience in building alliances in the past (and had beneficial results and practice at growing collaboration with outside or different partners), and a very clear mandate from the CEO and the Board of Director that the HVC being built is of potentially central importance for the future of the company.

Finally, for all social entrepreneurs, HVCs only make sense if they believe that by pursuing these commercial approaches in partnership with large corporations, they will be able to achieve a significantly larger impact.

2. What guidance is there for those who want to build HVCs

Here are several key lessons we’ve learned:

Create an HVC with the patience of a saint, but the persistence of an entrepreneur.

It takes a unique blend of management/leadership skills to forge an HVC: empathy and fairness, clarity and humor, finesse to create respect and trust among people who don’t move in the same business or social circles in life and a tolerance for diversity are all required. Ask a respected neutral convener with these skills and multi-stakeholder experience to lead sessions, at least for the first six months, to evolve a diverse group into a working team.

Plan to do several things at the start:

- design small joint tasks that are low-risk with short-term successes to get them working together and appreciate each other’s talents and experience;

- hold partners’ hands warmly and often;

- communicate progress of the HVC framework widely -- so it begins to appear/be heard in the news, on radio and TV, at professional events, on Twitter and Facebook, blog sites and networking conversations;

- have sufficient funding to not rush the process at the start;

- search for best practices to adapt from pioneers who have forged a successful HVC to fast track initial steps as much as possible.

Create a shared vision and goals. Articulate them in hybrid language.

Help new HVC partners make a U-turn from getting stuck by how different their assets/work/life/styles are. Remind them often the reasons they showed up: There’s a huge social unmet need (which charities, government programs, and they have not been able to solve at scale); which means an equally huge potential business opportunity (which they have not yet accessed); and none of them can do it alone. Remind them often how valuable each of their assets, knowledge, experience and strengths are in this venture.

Use language reflecting hybrid values from the beginning. It will help you to create mindset changes that will make differences easier to discuss and collaboration easier to envision. Speak with equal emphasis about wealth creation and social impact through market-based approaches. Some of the best motivation to get corporations or investors involved in HVCs is to illustrate their recent failed attempts to use traditional business models in new markets, so why not co-create a new model? Similarly, citizen organizations are frustrated by not being able to raise enough funding to help all clients who desperately need their services. Make it clear these cannot continue to be mutually exclusive or tradeoffs. Clearly confirm that innovative solutions exist, and they will be found by working together. Remind them that scarcity is in their minds (cite the new wealth created by the invention of the internet, for example, solely reusing available resources in new ways). Show how their competitive edge will emerge from collaboration. Find examples of the benefits of collaborative entrepreneurship: small projects can get done with one strong leader and a small team, but big solutions –affecting the whole community and needing to be sustained over a long time (as with health care or corporate growth) – cannot be achieved by one perspective, one leader, one sector, and so on. Collaborative entrepreneurship is the key for reaching scale.

Choose corporate partners carefully.

In emerging HVCs, immediate or short-term benefits are few or less tangible. Corporations especially need to show quantitative ROI, and are accustomed to quarterly reports demonstrating success. HVCs don’t fit this model at the start. Engage from day one an internal champion with the capacity to convince corporate buy-in at the top and refuse to get involved unless this condition is met. This is not about one successful innovative project, this is about transforming companies from within. Therefore, pick a corporate partner who understands the value of patient capital, the real time it takes to develop an innovation, the means to support the time needed to gel a new team, and the willingness to sell this to the company’s board: Long-term gains will trump short-term profits. Choose a company which, despite a strong track record, feels stuck. They’ll need less convincing to try something new.

Ditto for citizen sector partners.

Select an organization that already feels the frustration of repeatedly serving client needs and never making a significant difference in their lives. Build a relationship with a social entrepreneur who is ready to embrace market based approaches without ideology getting on the way. Look for citizen sector professionals able to hold their own at the table and to think and act outside the box. Look for the outliers who are already experienced in being part of system-wide solutions that reduce clients’ dependency and enable them to grow into full economic citizens. Choose organizations with fairly stable funding, and that have organized projects that require teamwork – both internally and with other organizations -- and have the staff level to lead. Many will need capacity building (to communicate without barriers with their corporate partners) and you can help get that for them over time (Ashoka HFA India –started with really savvy partners – and because of how good they are, they need to take on more responsibility – and we are this year beginning a CSO Support Network to help them build the new skills and management systems they need).

Never think you’ve finished the R in R & D.

Running an HVC is like doing the dishes. You are never done. Just when you think all the analysis and data about the sector have been gathered, some new obstacle or new opportunity appears, and you do not have at your fingertips the solutions to conquer or seduce it! Think back at the Ashoka HFA India example. Careful preparation for a year took place, strategies refined, everything discussed and strategies planned. And yet at almost every corner, new roadblocks appeared. Each required new learning, more reality-testing with multiple stakeholders’ perspectives. Yet rather than a setback or a delay (which temporarily they seemed to be) each, ultimately, added to the depth, resilience, confidence and stature of the HVC team, and opened new doors that lead to higher levels of growth and ability to scale.

3. What is needed for HVCs to reach scale and full global market potential?

After several years of hands-on experience, we saw real benefits from the HVCs we ran in the housing sector, as well as from examples in other sectors. Companies and citizens increased their income, developed innovations and products and new distribution systems they didn’t even know they needed! They learned how to increase their probability of success entering new markets. And both corporations and citizen sectors participating in HVCs report positive transformation of mindsets, to be humbled by how much they can learn from each other and convinced the way forward it to increase that collaboration.

Our own “aha” moment came after success. We realized that at this pace – building one HVC at a time, convincing one major corporation at a time, or even working in one sector at a time – we would not see industry-changing and broad social benefits in our lifetime! Therefore, our major lesson going forward is:

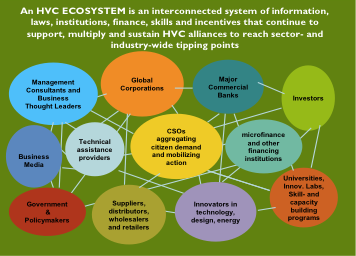

It takes an Ecosystem to make HVC changes in business frameworks, values and skills ubiquitous.

For HVC to take hold, it needs thousands of corporations, in dozens of countries, affecting millions of people, producing billions of new revenues for the momentum to reach a tipping point and accelerate change. If the metaphor for a single HVC is the DNA double-helix, the metaphor for an HVC ecosystem is the interrelated synapses of the brain – an enormous complex constantly communicating system with multiple functions, diverse styles and complementary strengths.

The HVC ecosystem has the same diversity of stakeholders as does an individual HVC – but more join at higher levels of responsibility and impact. At some point in an HVC’s growth, regulations or laws, roads or tax incentives, public sewage systems and municipal services, significant amounts of capital investment or capacity-building will be needed. Our future work is to build awareness, consolidate and share the value, and build relationships with those who will champion HVC in larger institutions: universities with MBA and Executive Education programs or cutting-edge, interdisciplinary global innovation labs, management consultants who will translate concept into solid management practices across the for profit and citizen sectors; business media to share HVC stories and lessons widely, and building a supportive global community who continue to nurture each other in dynamic ways to find solutions to scale.

Ecosystems are functional, but they also create the environment that allows the bigger story of human and business transformation to grow.

HVCs now spend necessary but long work convincing essential players to join: the more conservative or risk-averse, the harder to get them on board. But imagine if bankers, CEOs, policymakers, top economic consultants, management experts, government leaders, MBA professors and the most respected business and public thought leaders all were writing and blogging not about HVC as innovation, but about tangible HVC benefits emerging in sector after sector, region after region. About the excitement of a movement toppling silos and gaining adherents everywhere. Then the questions are not if investing in an HVC is right, but how can we build then better, cheaper, faster? What’s my role in this? What can I do? How will making HVCs more powerful enhance my own success? Those who lead HVCs need to have one eye on their daily tasks, while the other sees far ahead to build commitments well into the future and at levels no one HVC alone can achieve.

Innovative management consultants are key to spreading HVC practice into standard operating procedure.

The current conventional corporate wisdom of “shareholder as king” was once only an idea promulgated by management consultants, who then developed the practices enabling thousands of CEOs and hundreds of thousands of line or function managers to implement them. Just as that sea change about corporations’ purpose happened 40 years ago, now is the time for them to play an important enabling role to make a new 21st century vision, framework and set of practices viable for corporations, as well as become new revenues streams for themselves.

Building HVC entrepreneurship and practitioner capacity is essential.

If we could wave a magic wand and tomorrow create 1,000 HVCs in a dozen major sectors, we would not find 1,000 CEOs, 6,000 corporate line managers, 3,000 citizen sector organizations to lead 30,000 local community groups to be strong partners in them. Nor would banks know how to process and serve millions of new customers ready to enter a formal economy. At all levels, capacity-building must be addressed.

This is a huge opportunity for universities, private and public technical schools. Business academic leaders in MBA and executive education programs and inter-disciplinary innovation labs are a cutting-edge source of skill-building for current and emerging business and social leaders. Why not offer courses in HVC frameworks, metrics and hands-on HVC innovation or application internships? CEO boot camps for industry leaders have been career- and life-changing, to quote alumni of Harvard’s. Why not develop HVC executive boot camps to match CEO vision with match HVC leadership qualities? Or help develop HVC skill-building courses offered through networks of private and government-funded technical institutes, just as they do when more contractors or engineers versed in LEED or green building standards are needed?

Multiple messengers are needed to raise awareness, document progress and champion HVC work.

Social entrepreneurship and frameworks like HVC need serious business media to cover them with the same gravitas as they do the stock market or mergers and acquisitions. Corporate HVC first-movers need to share their vision broadly with their Boards, their company as a whole, and their colleagues – who will respect and “hear” their messages more clearly from a respected peer with examples from their sector to answer next questions. We at Ashoka need to establish tools for the global HVC community of practitioners (or those who want to become them) to get information openly, share best practices, get assistance when needed, meet online potential talent or partners for their own HVC to grow. And we need to do this collaboratively, making the platform interactive, both a source as well as a magnet for new information, innovative solutions, places where needs find resources or offers, where deals can be sparked, mentors identified. Organizing this global community of HVC entrepreneurs, practitioners, resources, knowledge and talent will parallel our work to build ecosystems, capacity and momentum for HVC to meet the challenges of scale.

FEC values and HVC frameworks are the new “green” for the 21st century.

By the close of the 20th century, multinational corporations in mining, fishing, chemical production, timber and other sectors were vilified as their practices ravaged the environment. Class action lawsuits abounded (and some succeeded). But immediate wealth continued to accrue to these companies, so few if any deep changes were made.

Enter Stephan Schmidheiny, founder of the VIVA Trust, a legendary business leader and philanthropist who incentivized grant seekers to think of grants not as gifts, but as investments, and to use as many entrepreneurial, for-profit management skills as possible to frame their idea’s model and sustained success. Through a series of high-level meetings, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development was founded. Its ranks have swelled to hundreds of largest global corporations today.[20]

A firm believer of “what doesn’t get measured, doesn’t get fixed,” WBCSD developed consensus around required principles (e.g. transparency, willingness to share best practices) and expectations: an annual report card of members’ movement toward a series of environmental improvements each year. That all members agreed was pretty amazing, and skeptics assumed it would be window-dressing or good public relations, but not real changes in practice.

But over the past decade, WBCSD has in fact tracked improvements in a dozen criteria for better stewardship and management – in some of the most difficult industries to change. It launched many innovative “inclusive businesses models,” many of them similar to HVCs, which developed completely new ways for their members to get rich and provide jobs, income and significant social value while meeting their environmental goals.

Cynics said they’d never change the mining or timber or petroleum industries. But in fact, they’ve made significant changes. With seven billion people now on the planet, growing to over 10 billion by 2030, with two-thirds off the grid, “sustainability” takes on heightened importance. We will not solve environmental degradation or poverty until we see them as dependent upon each other. Solutions for one mean solutions for both. Citizen income and corporate profits. AND, not OR. Sustainability must include in its definition the long-term future of wealth creation for both the private and the citizen sectors – for only then will we tap into everyone’s desire, ideas, creativity and persistence to develop a better future. Citizen and business sectors joined by mutual goals, co-creating the practices to get to success for both, will be the best tonic capitalism can get for its long-term renewal and rewards.

Ultimately, creating ecosystems that will be strong and flexible enough to multiply disruptive innovations in service of reinvigorating capitalism through HVCs and FEC values requires holding the vision of a better possible future, great respect for the strengths others offer to the whole, and great willingness to move among teams of teams – leading some, being a supportive member in others. It takes all of them truly believing their collaborative path is more effective than the old models of the past (even if messier at the start). What gets all this to continue are the win-win-win set of goals and the hybrid value chain framework as the engine.

At Ashoka, we believe that in order to realize the full potential of these markets, all actors involved -- from builders and housing materials corporations, to bankers and investors, to citizen organizations working in local communities linking potential consumers to the formal market -- need to see themselves as changemakers, who by joining their assets and strengths together are making possible the global transformation of industry for sustained wealth creation and social impact. And that is the most hopeful vision for long-term robust capitalism.

SIDE BAR: HVC SNAPSHOTS FROM OTHER SECTORS

The Social Need: Worldwide: each year, over 2.5 million young children die of preventable, water-carried disease. Moreover, severe drought has made access to water – especially potable water – a serious issue for all ages, populations, regions of the world. In India alone, over 400,000 children under the age of 5 die each year due to diarrheal diseases transmitted by contaminated water.

The Business Opportunity: Demand in India and many other countries for safe drinking/cooking/bathing water at low cost still greatly outstrips supply. Room for increased market share for companies who can deliver water at low cost to reach all who need it and drive the price per family as low as possible.

WaterPoints in India: eHealthPoint (EHP) includes safe water as an essential pillar of its Health For All goals. It purifies the local water to provide a safe supply, which villagers come each day to collect. The water treatment process uses modern reverse osmosis technology to remove bacteria, fluorides and other contaminants.

- It costs a family five cents a day a month’s supply of water from an EHP unit.

- In 2011, EHP provided 50,000 people per day with safe drinking and cooking water.

- Because people come to pick up their water daily, EHP has multiple opportunities to raise awareness about health issues and encourage early treatment of medical conditions. Coming to get water also provides social cover for visiting the EHP unit for patients with socially-unacceptable or embarrassing conditions, such as tuberculosis, STDs, contraception, unwanted pregnancies or HIV.

- Since its inception, providing clean water at EHP has financed the development of the clinics. Early in 2011, EHP broke even (water sales totally covered all costs of purification and all health care services), and is now generating net profits to scale up the model throughout India and launching pilots in other countries.

Partners:

- Ashoka contributed to eHealthPoint’s startup and its co-founders, Al Hammond and Ahmet Jain, created eHealthPoint as a unique for-profit venture that includes multiple alliances with businesses, local health workers from the citizen sector, investor and foundation support when appropriate.

- EarthWaterFoundation is a global CSO dedicated to promote interactions with leading water scientists on the future of water, the earth’s most valuable commodity, and promote access to water for people worldwide.

- Fontus Water Ltd. offers complete water and wastewater treatment solutions to the buildings and industrial sector and is the company providing the purification systems for eHealthPoint water.

Results to date: 50,000 families were served in 2011; expansion means by end of 2012, that rises to over 100,000 daily.

LOW-COST HIGH QUALITY HEALTH CARE

The Business Opportunity: Fix the broken health care value chain by unifying currently fragmented pieces of comprehensive health care: integrate prevention (water), local one-stop sites for delivery, train rural health workers to improve health education and follow up; use the sale of water to underwrite initial costs; set up systems of telemedicine to increase quality and reduce costs of tests, diagnoses, and access distant specialists; develop mobile apps to integrate, archive and update patients’ medical records at low cost; aggregate and certify pharmaceutical providers to ensure quality and low cost; which together create net revenues to repay investors, expand the model and sustain it.

Partners: eHealthPoint works with networks of citizens, doctors, hospitals, local community health care workers, several companies with networks of local pharmacists; technology companies developing the e and m health apps and interfaces.

Results to date: In 2011 eHealthpoints were breaking even from water sales; by 2012, diagnostic tests and pharmacies were adding revenue, even at well-below-market prices to patients; 70 operating waterpoints and 8 operating eHP clinics in the Punjab region of India, and is adding 20 water units per month. EHPs are providing 11,000 high quality diagnostic tests an average of eighty cents each; 25,000 medical consultations between $1-$4 each; , and filled over 27,000 prescriptions through just one of its pharmacy partners, Good Luck pharmacy.

Social Need: Over 107 million Mexican people (20% alone in Mexico City) in 80% of all households live below the official poverty level. Unemployment is high, the “informal economy” accounts for sporadic and risky work. Skill levels are low; violence is high, street gangs rule. There are few if any appropriate jobs for women heads of households – most with young children are unemployed – or for vulnerable youth – living in poverty, dropping out of school and joining gangs as a source of a close-knit “street family” which provides income, albeit illegal. Mexico also has the world’s highest rates of childhood obesity; among adults the obesity epidemic is growing: 72% of women and 67% of men are obese; 38% suffer from anemia and other illnesses related to malnutrition.

The Business Opportunity: Danone, already well-established in Mexico, wanted to increase its market share in Mexico by building greater brand loyalty and opening new markets (e.g. those at the base of the pyramid, where consumption of their products was low) in Mexico and Latin America. They especially highlighted targeting increased sales of its yogurt and other dairy products to poor segments of the economy, those suffering also from poor nutrition, low-skills for jobs and obesity.

The HVC Solution: Create Semilla, a direct sales channel based on a program of “Business/Skills for Life” for Danone to hire locals to reach consumers in informal and low-income markets and to build skills with its curriculum, training and job opportunities to low-income women and youth. It also serves as an innovation lab for Danone to get input for new product and distribution development. The program

- Trains and employs low-income women heads of households and vulnerable youth to sell Danone and Bonafont products door to door, on streets and in markets.

- Increases in adult household income allows children to stay in school, and provides better housing, lower crime rates, domestic violence. Provides attractive options for youth to drop out or avoid gang membership because they have income through this work and a new. positive “extended family” to provide guidance for legal ventures and a better future.

- Educates this sales force about nutrition, encouraging them to spread the word about better food choices. Spread of nutrition education and more nutritious products in marketplace expected to reduce obesity rates.

- Include low-income citizen sales force to develop new or modified Danone products to fit better with market preferences and costs.

Partners:

- Semilla to train the sales force, link sales input into new products in Danone corporation.

- Danone Ecosysteme provides funds for project startup, links input for new products Danone corporation.

- Cauce Ciudadano, the leading CSO begun by former gang-member-turned-Ashoka-Fellow Carlos Cruz , working with youth to reduce gang involvement, break cycle of street violence and increase youth graduation.

- A network of local community organizations help recruit low-income women to the program.

- Ashoka FEC Mexico incubated the project, devised strategy, convenes all stakeholders including multiple citizen sector organizations; monitors and coordinates growth in Mexico

Results: On track to employ 4,000 Mexicans full-time by 2015, increasing their incomes sufficiently to move from economic exclusion to inclusion. Project broke even in 2009, has been profitable since, and is now in expansion phase. Cauce Ciudadano just won a global award for its achievements: proving a comprehensive program of education, social inclusion, counseling and skills to earn income legally for the over 75,000 youth between 11-21 ripped from their families to live as part of organized crime in Mexico. Youth who pass through Cauce Ciudadano, criminal recidivism is 24%, compared to over 85% among youth in other court-ordered programs on a fraction of their budgets.

ACCESS TO A $90 BILLION MICRO-INSURANCE MARKET

Social Need: In Mexico, less than 7% have life insurance, compared to 67% in the US. Most of Mexico’s insured live in cities, where they are covered through the government or company jobs. But when a wage-earner dies in a rural area, funeral costs and reduced household incomes devastate families living far from a social safety net. Widely-scattered and remote, it is hard for insurers to achieve the scale needed to distribute low-cost, low-margin policies. Insurers generally stick to serving higher-income segments, where fewer transactions net higher margins – ignoring the rural poor.

Business Opportunity: Industrialized countries account for 89% of the global life insurance market, with an annual growth rate of 5%. Emerging markets average double-digit insurance gains, a much greater potential for growth. If every low-income Mexican had access to life insurance, it would mean $2 billion in new annual sales for the insurance sector. Globally this increases to a new $90 billion untapped BoP market. The barrier: adapt insurance products, costs, marketing and sales to remote rural families, and aggregate demand inexpensively, and interest large firms to implement with stable underwriting ability.

HVC Collaboration: Match Zurich Financial Services, the world’s fifth largest insurer, to AMUCSS, s Mexican social enterprise founded by Ashoka Fellow Isabel Cruz, which grew into a 100-microfinance network serving over 350,000 rural farmers. Collaborate to develop and test new affordable life insurance products, train locals to market them, build relationships with underwriters to guarantee loans.

Partners:

- Zurich Financial Services, the world’s fifth larger insurer, and now claims more than a million low-income customers in 11 countries including China, Russia and South Africa; Bolivia, Brazil and Mexico.

- Red Sol, the social enterprise created to sustain these allied efforts

- Ashoka to consolidate and systematize learning and spread of the model

Results:

- Seven new life insurance policies (from $2-$40 per year, with payouts of $385 - $8,000), did away with signature requirements (costly to collect); developed electronic scanners to send paperwork from a network of 70 rural microcredit agencies to promote new insurance options. Reduced costs by extending credit so clients could pay annually, succeeding in aggregating sufficient clients to interest a major global insurance company.

- Zurich Financial Services assumed all financial risk to underwrite the policies, co-developed the new policies and helped train the microcredit agents to market policies and provide financial education to clients. Results: policies climbed from 1,336 in 2005 to over 150,000 policies by end of 2011.

- AMUCSS success in micro-life insurance has sparked it to develop a micro-health insurance product and process for this sector.

- Success in Mexico spurred Zurich to grow elsewhere, even outside the BoP. Zurich Spain teamed up with BancoSol, the largest Bolivian micro finance institution with presence in Spain, to offer micro-life insurance to more than 250,000 Bolivian immigrants living in Spain. They are a segment of more than 6.4 million immigrants in Spain.

Rochelle Beck

Bill Drayton

Chip Reeves

Stephanie Schmidt

Steven Serneels

Vishnu Swaminathan

Our local and global HVC corporate and citizen partners who ignite our passion, humble us with their resilience and sparkling innovations, and share their insights to spur us to greater results and new challenges.

1. To learn more about Hybrid Value Chains see: Valeria Budinich and Bill Drayton, “New Alliance for Global Change,” (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Business Review, September 2010). https://archive.harvardbusiness.org/cla/web/pl/product.seam?c=15952&i=15...

2. Read Beverly Schwartz, Rippling: How Social Entrepreneurs Spread Innovations Throughout the World (Josey-Bass, March 2012); and David Bornstein, How to Change the World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007); and visit www.ashoka.org.

3. See http://www.colorado.edu/studentgroups/libertarians/issues/friedman-soc-resp-business.html. For a 2007 review of its impact on business, see: http://www.worldchanging.com/archives/005373.html. Other economics and business professors promoted the narrow goal of shareholder maximization, called Agency theory, and informed entire new portfolios for management consultants for over three decades. See http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~dobbin/cv/book_chapters/2010_Dobbin_Jung.pdf

4. See C.K. Prahalad, Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits (Pearson Press, 2006. http://books.google.com/books/about/The_Fortune_at_the_Bottom_of_the_Pyramid.html?id=R5ePu1awfloC. Prahalad suggested managers look beyond the confines of traditional business models to learn about the disruptive innovations being developed by social entrepreneurs --developed by citizen sector organizations (e.g., CEMEX and Grameen micro-lending model applied to progressive home building in slums) and/or social entrepreneurs advancing profitable models to scale impact (e.g., the innovative business model of Aravind – blindness prevention and eye care for all at affordable prices).

5. See C.K. Prahalad and Stuart L. Hart, “Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid,” published in 2000, at http://www.stuartlhart.com/sites/stuartlhart.com/files/Prahalad_Hart_2001_SB.pdf

6. Intrigued by the size of untapped BoP markets, many companies rushed in: with their cheapest lines of products, outdated/discounted products, or rebranded older products now in decline in traditional markets. Some made efforts to interact with BoP consumers, but used their same staff, metrics and processes –resulting in products or distribution networks that failed in these low-income communities. Most never partnered with local experts about need and product details, and they did not think about creating new products or services of high value at low cost. The ones that spent more time and developed better product adaptations succeeded initially. But lacking a new framework that connected them to larger citizen partners and wider distribution, financing and sales, they did not succeed in making their initial small investments succeed at national scale, and their interest in the BoP fizzled when their multi-million dollar profit expectations were not realized.

7. Ashoka named its new framework a hybrid value chain, recognizing Michael Porter’s value chain as a concept giving managers a clear sense of the value each industry player has from idea to product to sale. By adding the word hybrid, Ashoka FEC transforms it into a roadmap for future business success built by teams of multiple and new players at the sweet spots where each adds both business and social value.

8. HVC is a powerful management hack: its criteria deliver social and business value, at scale, including citizens’ acceleration to full economic citizenship, and they produce sector-wide, sustainable outcomes. When Ashoka began writing about HVC, there were few ideas that had changed business as usual. More recently, others have come along. While each have benefits, they fall short on one or more important criteria:

- Public Private partnerships, while including more than one stakeholder, need not include the citizen sector, may not add much diversity, and don’t fundamentally change a business framework. They are a good way for the public to subcontract with the private sector when its skills and experience exceed a public agency’s budget, personnel or time constraints. But a state paying with tax dollars for the land and constructions of a major highway, then giving a 99-year lease to a private company to manage its tolls and maintenance, for example – while efficient for both partners – won’t transform the transportation sector or help citizens on a road to full economic citizenship .

- CSR can be many things: in-kind donations to offset costs of schools or community services, volunteers donating time to nonprofit organizations, paid employee leave to be a volunteer in a community, using funds to cut back on polluting the environment, organizing cleanups of the environment, etc. While all these activities serve communities, they do not change the old pattern of “charity” and “kindness” or helping “the poor” or sharing with “recipients.” There is no sense of co-creation. Nor does CSR change core wealth creation centers of the company. They do not empower their beneficiaries to become independent changemakers, and do not achieve –even with large amounts of hours or dollars – the framework change that leaves in place citizen-business alliances continuing to work together for larger market pies and value.

- Corporate Foundations support many innovations coming from the citizen sector (and indeed Ashoka’s initial applications of HVC were made possible by grants from the Hilti Foundation, Danone Ecosysteme, Patrimonio Hoy of CEMEX, etc.) Often these foundation leaders see and share our objectives. Ultimately, however, as with CSR, they operate on the margins of the corporation, and their impact is not embedded in the 99% of the corporate staff or activities producing its core revenues. The best of these professionals do valuable work for society and corporate brand loyalty – but their actions often cannot compete with line managers producing wealth.

- Inclusive businesses or b-businesses have grown In the past couple of years (the former, a model used by many Ashoka Fellows, is a private for-profit company relying on market forces but with a an integral goal and set of strategies that create social value by including citizens and their organizations as key stakeholders in the mix. The latter – also known as a “Benefit Business” -- is a new legal structure for a for-profit business that does not show a profit because it plows revenues back into social benefit work.) These models come close to an HVC in their respect for private market incentives and forces, inclusion of citizens, passion and good management, and transcending old management models and tradeoffs. Most, however, have started with the intention to fix a local broken value chain. As yet, few have grown large enough to achieve large scale. It remains to be seen whether their model and their leaders have the skills to continue to maximize social good AND make enough profits to grow to scale.

- Shared Value. Shortly after we published the HVC framework in HBR in late 2010, Michael Porter and associates published the concept of “Shared Value.” Much of values, frameworks and recommendations reinforce those of HVC. It’s the title that is not quite right. If one doesn’t read the fine print of the article, one thinks it is endorsing “sharing” the value created by the company with those less fortunate. Not what the authors had in mind, but nevertheless, a major stumbling block to change the framework at the zeitgeist level of corporations’ relationship with society.

HOW HVCs RELATE TO OTHER SOCIAL- BUSINESS ALLIANCES

9. Examples of this last HVC criterion abound: Yunus’ model of microcredit attracted so many new finance institutions and investors that a whole new global microfinance sector arose to generate sustained, new profits. Applying tele- and mobile communications technology to health records, tests, diagnoses and treatment has lowered costs and increased access and quality in health care services, while attracting multiple suppliers of water purification systems, high quality pharmaceuticals and specialist services to serving low-income populations. Bundling low-interest loans with technical assistance to small farmers increases their yields by between 50-200% and gives them access to global markets and multiple choices of buyers. Changing the cost structure for producing solar panels in high volume gives low-income people living off the electric grid access to inexpensive energy, stop burning coal or wood for cooking and heating, improve their health, protect the environment and generate excess energy sold to public utilities to reduce rates or make new innovations possible.

10. FEC’s focus on new framework development and applications has been in India, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Egypt, and Indonesia. FEC priority sectors are: affordable housing, water, health care, alternative affordable energy, nutrition security, aggregating smallholder farmers to improve quality and revenues, innovative and competitive financial products for low-income populations, and the application of ITC to these sectors to increase transparency, access, reduce costs. See SIDEBAR for Ashoka HVC project highlights. For new looks at innovative frameworks akin to HVC, see: Susan Rae Ross, Expanding the Pie: Fostering Effective Non-Profit and corporate Partnerships (Sterling VA: Kumarian Press, 2012); and Philip E. Auerswald, The Coming Prosperity (Oxford University Press, 2012).

11. Budinich, Valeria and Drayton, Bill, “New Alliance for Global Change,” (Harvard Business Review, September 2010). https://archive.harvardbusiness.org/cla/web/pl/product.seam?c=15952&i=15...

12. To read in depth about the many innovations Ashoka HFA India developed, see the following articles recently published by Ashoka and Next Billion: Authors to read are Vishnu Swaminathan, Keerthi Kiran, Martina Wengle, and Melissa Scott in The BIG IDEA: Global Spread of Affordable Housing .http://viewer.epaperflip.com/Viewer.aspx?docid=a347fb86-fbbc-4424-bba7-a02100ce34b6

13. There are hundreds of campuses with core values and curricula aligned with the “Everyone a Changemaker” ethos of social entrepreneurs who can be sourced by visiting: http://ashokau.org/. Forward-thinking mayors, governors and other municipal officials too are adopting the open, collaborative process that HVC represents for planning cities or transportation, culture, social justice or governance. For more see: http://changenation.org/.

14. For more of Reeves’ and his staff’s experiences translating their experiences in India into product innovations back at Dow Corning, see articles by Reeves, Ronda Grosse and Frank DeLano in The BIG IDEA: Global Spread of Affordable Housing http://viewer.epaperflip.com/Viewer.aspx?docid=a347fb86-fbbc-4424-bba7-a02100ce34b6