Forget the Gig Economy—Most of us are still slaves to bureaucracy

Writing for Harvard Business Review in 1988, the renowned Peter Drucker predicted that in twenty years the average organization would have slashed the number of management layers by half and shrunk its managerial ranks by two-thirds. Yet despite the recent emergence of the “gig economy” and the “sharing economy,” there’s no evidence that bureaucracy is on the ropes—quite the opposite, in fact.

In 1993, 47% of U.S. private sector employees worked in organizations with more than 500 individuals on the payroll. Twenty years later, that number had grown to 51.6%. Large organizations, those with more than 5,000 employees, increased their employment share the most—from 29.4% to 33.4%.

Meanwhile, the percentage of Americans who are self-employed dropped to an all-time low. Today, of the roughly 120 million Americans working in the private sector, 62 million work in organizations that are big enough to have the trappings of bureaucracy. To this number we must add the 22 million souls who work in public sector organizations, where bureaucracy seems as inescapable and unremarkable as coffee-stained carpeting.

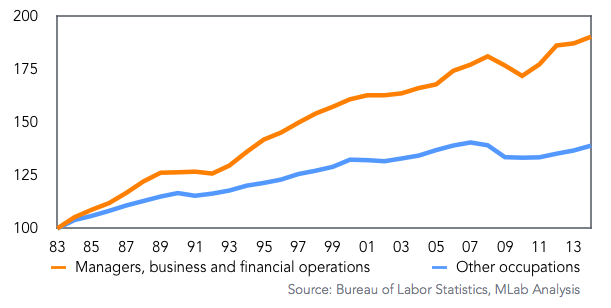

Within these organizations, the “bureaucratic class” has been growing, not shrinking. Between 1983 and 2014, the number of managers, supervisors and support staff employed in the US economy grew by 90%, while employment in other occupations grew by less than 40%. (See Figure 1). One finds a similar trend in other OECD countries. In the United Kingdom, for example, the employment share of managers and supervisors increased from 12.9% in 2001 to 16% in 2015.

Figure 1. Growth of managerial employment versus other occupations in the U.S.

(1983 = 100)

In some sectors, like health care and higher education, the bureaucratic class has grown even faster. In the University of California’s sprawling network, the number of managers and administrators doubled between 2000 and 2015, while student enrollment increased by just 38%. At present, there are 1.2 administrators for every tenured or tenure-track faculty member within the UC system.

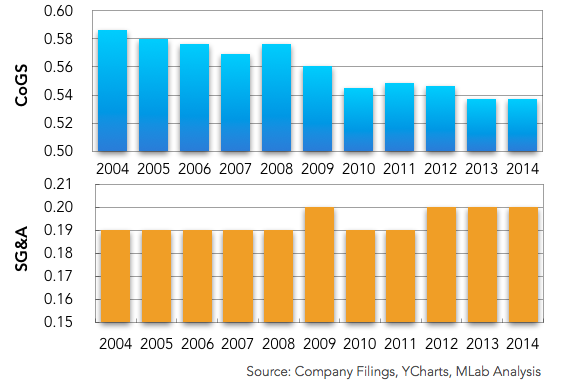

One might have expected successive rounds of downsizing to have pared back bureaucracy within the corporate sector, but this hasn’t been the case. Between 2004 and 2014, the companies comprising the S&P 500 reduced their average cost of goods sold by 500 basis points. Yet during the same time period, SG&A, which includes the costs of senior executives and corporate staffers, crept higher. (See Figure 2). It would seem that the enthusiasm for all things “lean” has its limits.

Figure 2. Median SG&A and cost of goods sold for S&P 500 companies

(Percentage of revenues)

While many CEOs decry bureaucracy, few seem to have a strategy for defeating it. Tactical victories—achieved by cutting a layer of management, reducing head office staff, or simplifying cumbersome processes—are usually small and quickly reversed. In this regard, look again at Figure 1. Notice how rapidly the thicket of bureaucracy grew back after being pruned in the wake of the 2008 recession.

It could be argued that in a world characterized by increasing complexity, the growth of bureaucracy is inevitable. Who else but senior executives are going to address all those vexing new issues, like globalization, digitization and social responsibility? Who else is going to meet all those new compliance requirements around diversity, risk mitigation and sustainability? Hence the recent surge in new C-level roles such as Chief Analytics Officer, Chief Collaboration Officer, Chief Customer Officer, Chief Digital Officer, Chief Ethics Officer, Chief Learning Officer, Chief Sustainability Officer and even Chief Happiness Officer. And more prosaically, who, if not managers, are going to do the everyday work of planning, prioritizing, allocating, reviewing, coordinating, controlling, scheduling and rewarding?

Apparently this is the consensus view of most CEOs, for if it it were otherwise, more of them would have launched sustained and effective campaigns to reverse the rising tide of bureaucracy.

Yet our research suggests that bureaucracy is not the inevitable cost of doing business in a complicated world. Rather, it is a cancer that eats away at economic productivity and organizational resilience. In the second of our three posts in this series, we’ll calculate the costs of excess bureaucracy for the U.S. economy and outline what can be learned from the growing ranks of the “post-bureaucratic” management vanguard.

In the meantime, we like to hear from you.

- What evidence do you see within your organization that bureaucracy is growing, not shrinking?

- Why do you think bureaucracy is booming despite countervailing trends such as decreased communication costs and shifting attitudes towards work individual empowerment?

To learn more about the $3 trillion price tag of excessive management, you can download our research paper here.

You need to register in order to submit a comment.

Michelle,

my 2 cents on your 2nd prism and question, I witness that even in places where empowerment is quite effective, especially in so called agile and lean organization, it is not at all entropy and bureaucracy proof. The root cause of it is in the word "individual".

As long as collective intelligence does not reach a "meta-level", that is to say the ability to change the decision-making processes, cheap communication costs do not solve the issue of decision speed and transparency.These last two elements are the only factors of enthalpy, that is the capacity to bond and link all kinds of relations drving the global effectiveness and sustainability of any system.

Because most remain to the basic level, companies keep adding staff and control means.

Wrong pick and high cost of re-insurance.

- Log in to post comments

Michelle,

good to read some inspirational material.

Very much in sync with the reality.

Good news, we are rapidly switching from the times of awareness to action mode. Academic data are now confirmed with field experience.

Acid test is positive.

Numbers are pretty much aligned with the early days evaluation : entropy, that is to say the increase of complexity or the energy leaks, or some combination ot the two are measured beyond the 10% mark per year. Corrected from necessary complexity due to growth and extension of playing fields a golden number of 7% seems to be the correct assumption for anyone starting to touch that field.Not 100% bureaucracy but the bulk of it fits the definition.

My new assignment for 18 months now. Very addictive domain.

I wish it helps.

- Log in to post comments