M-Prize Finalist

This hack is one of 24 outstanding entries selected as finalists in the Long-Term Capitalism Challenge, the third and final leg of the Harvard Business Review / McKinsey M Prize for Management Innovation.

Hack:

CSR 2.0: Reinventing Corporate Social Responsibility for the 21st Century

This hack is based on the premise that modern corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a business, governance, and ethics system has failed, and that it needs to be replaced by a new approach—CSR 2.0. Moving from CSR 1.0 to CSR 2.0 requires adopting five new principles—creativity, scalability, responsiveness, glocality, and circularity—and embedding these deeply into an organization’s management DNA. The essence of CSR 2.0 is that it is transformational, and offers a practical strategy for creating long term capitalism.

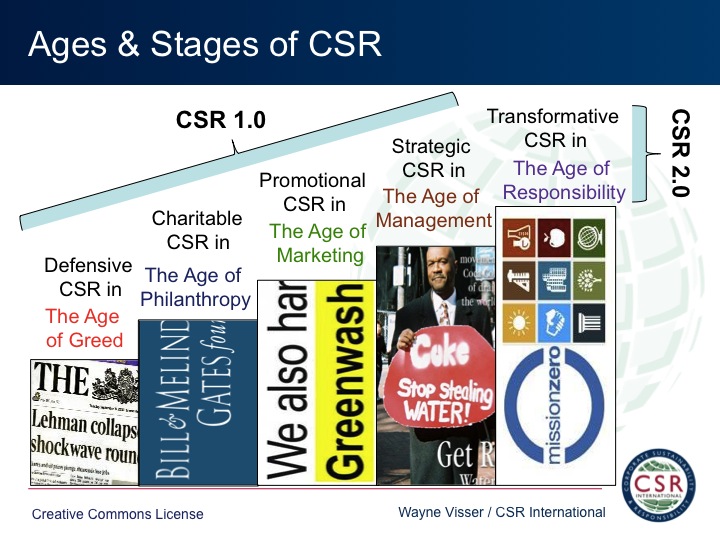

The Rise and Fall of CSR

The concept of CSR is not new, and has evolved over time. The modern concept of CSR can be traced to the mid-to-late 1800s. Industrialists such as John H. Patterson of National Cash Register seeded the industrial welfare movement while philanthropists such as John D. Rockefeller set a precedent that is echoed today in the work of business titan such as Bill Gates.

CSR entered the popular lexicon in the 1950s with R. Bowen’s landmark book, Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. The concept was strengthened in the 1960s, with, Rachel Carson’s critique of the chemicals industry in “Silent Spring” that helped to birth the environmental movement. CSR gained momentum in the consumer arena with Ralph Nader’s triumph over General Motors and its unsafe automotive manufacturing processes.

In the 1990s, CSR was institutionalized with standards such as ISO 14001 (an environmental standard) and SA 8000 (a labour standard), guidelines such as the Global Reporting Initiative and corporate governance codes that include Cadbury and King. During the 21st century . a plethora of CSR guidelines, codes and standards have been spawned (there are more than 100 listed in The A to Z of Corporate Social Responsibility).

Despite this steady march of progress, CSR has broadly failed. We are in fact witnessing the decline of CSR, that will continue until its natural death, unless it is reborn and rejuvenated. While CSR has had a positive impact on both communities and the environment, its success should be judged within the context of the total impact of business on society and the planet. From this perspective, CSR has failed on virtually every measure of social, ecological and ethical performance we have available.

A few facts will suffice to make the point: our global ecological footprint has tripled since 1961; WWF’s Living Planet Index shows a 29% species decline since 1970; and 60% of the world’s ecosystems have been degraded, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. We do not fare much better on social issues: according to the UNDP, 2.5 billion people still live on less than $2 a day; 1 billion have no access to safe water; and 2.6 billion lack access to sanitation.

There is also little good news to report on ethical issues. In 2007, 1 in 10 people around the world had to pay a bribe to get services. Prior to Enron’s collapse in fraudulent disgrace in 2001, Fortune magazine had voted it one of the ‘100 Best Companies to Work for in America.’ Worryingly, Enron had all the CSR codes, reports and practices you would expect from a socially responsible company. Lehman Brothers' story was worryingly similar.

‘Houston, we have a problem!’

The Failure of CSR

Why has CSR failed so spectacularly to address the very issues it claims to be most concerned about? This comes down to three factors – the Triple Curse of Modern CSR:

Curse 1: Incremental CSR

One of the great revolutions of the 1970s was total quality management, conceived by American statistician W. Edwards Deming, perfected by the Japanese and exported around the world as ISO 9001. At the very core of Deming’s TQM model and the ISO standard is continual improvement, a principle that has now become ubiquitous in all management system approaches to performance. The most popular environmental management standard, ISO 14001, is also build on the same principle.

There is nothing wrong with continuous improvement per se. On the contrary, it has brought safety and reliability to the very products and services that we associate with modern quality of life. But when we use it as the primary approach to tackling our social, environmental and ethical challenges, it fails on two critical counts: speed and scale. The incremental approach of CSR, while replete with evidence of micro-scale, gradual improvements, has completely and utterly failed to make any impact on the massive sustainability crises that we face, many of which are getting worse at a pace that far outstrips any futile CSR-led attempts at amelioration.

Curse 2: Peripheral CSR

Ask any CSR manager what their greatest frustration is and they will tell you: lack of top management commitment. This is ‘code-speak’ for saying that CSR is, at best, a peripheral function in most companies. There may be a CSR manager, a CSR department even, a CSR report and a public commitment to any number of CSR codes and standards. But these do little to mask the underlying truth that shareholder-driven capitalism is rampant and its obsession with short-term financial measures of progress is contradictory in almost every way to the long-term, stakeholder approach needed for high-impact CSR.

The reason Enron collapsed, and, indeed, the reason that our current financial crisis spiraled out of control, was not rogue executives or creative accounting practices, but rather a culture of greed embedded in the DNA of the company and the financial markets. It is difficult to find many substantive examples in which the financial markets reward responsible behavior.

Curse 3: Uneconomic CSR

If there was ever a monotonously repetitive, stuck record in CSR debates, it is the need for the so-called ‘business case’ for CSR. CSR managers and consultants (even the occasional saintly CEO) are desperate for compelling evidence that ‘doing good is good for business’ (i.e. CSR pays). Indeed, the lack of sympathetic research is no impediment for these desperados endlessly incanting the motto of the business case, as if it were an entirely self-evident fact.

The more ‘inconvenient truth’ is that CSR sometimes pays, in specific circumstances, but more often does not. There is low-hanging fruit – like eco-efficiencies around waste and energy – but these only go so far. The hard-core CSR changes that are needed to reverse the misery of poverty and the sixth mass extinction of species require strategic change and massive investment. These may be lucrative in the long term, economically rational over a generation or two, but we have already established that the financial markets don’t work like that; at least, not yet.

CSR 1.0: Burying the Past

CSR must be seen for what it is: an outdated, outmoded artifact that was once useful, whose time has passed. If we admit the failure of CSR, we may find ourselves on the cusp of a revolution, like the one that transformed the internet from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0. The emergence of social media networks, user-generated content and open source approaches are a fitting metaphor for the changes CSR must undergo to redefine its contribution and make a serious impact on the social, environmental and ethical challenges that the world faces.

For example, just as the internet of Web 1.0 moved from a passive audience content consumption approach to a collaborative mode of Google-Facebook type interaction, CSR 1.0 is starting to move beyond the outmoded approach of CSR as philanthropy or public relations (widely criticized as ‘greenwash’) to a more interactive, stakeholder-driven model. Web 1.0 was dominated by standardized hardware and software, while Web 2.0 encourages co-creation and diversity. So too in CSR, where we are beginning to realize the limitations of the generic CSR codes and standards that have proliferated in the past 10 years.

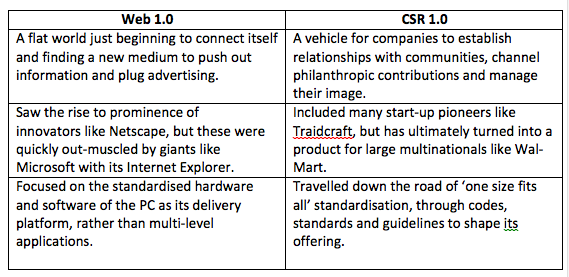

The similarities between Web 1.0 and CSR 1.0 are illustrated in the following table.

If this is where we have come from, where do we need to go to? The similarities between Web 2.0 and CSR 2.0 are illustrated in the following table.

CSR 2.0: Embracing the Future

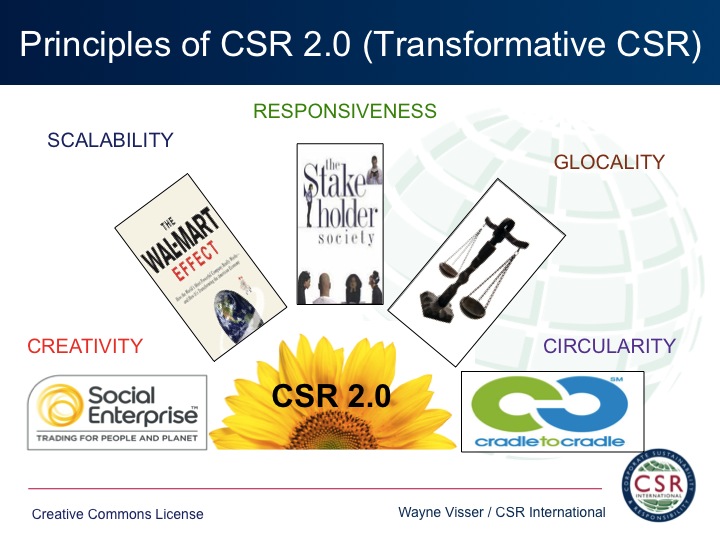

If this is where we have come from, where do we need to go to? Let us explore in more detail this revolution that will, if successful, change the way we talk about and practice CSR and, ultimately, the way we do business. There are five principles that make up the DNA of CSR 2.0: Creativity, Scalability, Responsiveness, Glocality and Circularity.

Figure 1: The Principles of CSR 2.0

Principle 1: Creativity

In order to succeed in the CSR revolution, we will need innovation and creativity. We know from Thomas Kuhn’s work on The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that step-change only happens when we can re-perceive our world, when we can find a genuinely new paradigm, or pattern of thinking. This process of ‘creative destruction’ is today a well accepted theory of societal change, first introduced by German sociologist Werner Sombart and elaborated and popularised by Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. We cannot, to a paraphrase Einstein, solve today’s problems with yesterday’s thinking.

Business is naturally creative and innovative. What is different about the Age of Responsibility is that business creativity needs to be directed to solving the world’s social and environmental problems. Apple, for example, is highly creative, but their iPhone does little to tackle our most pressing societal needs. By contrast, Vodafone’s M-PESA innovation by Safaricom in Kenya, which allows money to be transferred by text, has empowered a nation in which 80% of the population have no bank account and where more money flows into the country through international remittances than foreign aid. Or consider Freeplay’s innovation, using battery-free wind-up technology for torches, radios and laptops in Africa, thereby giving millions of people access to products and services in areas that are off the electricity grid.

All of these are part of the exciting trend towards social enterprise or social business that is sweeping the globe, supported by the likes of American Swiss entrepreneur Stephen Schmidheiny, Ashoka’s Bill Drayton, e-Bay’s Jeff Skoll, the World Economic Forum’s Klaus Schwabb, Grameen Bank’s Muhammad Yunus and Volans Venture’s John Elkington. It is not a panacea, but for some products and services, directing the creativity of business towards the most pressing needs of society is the most rapid, scalable way to usher in the Age of Responsibility.

Practical steps to increase creativity include: 1) Building social and environmental critieria into the core R&D function, as Nike has done with its Considered Design, and open sourcing selective patents, using facilities like GreenXchange. 2) Having forums, suggestion boxes and competitions where employees and other stakeholders can have their innovative ideas recognised and rewarded. 3) Actively supporting, investing in and partnering with social enterprises, social entrepreneurs and "intrapreneurs" (entrepreneurs within the organisation). 4) Having diverse stakeholder representation on advisory boards and acting as non-executive directors that can challenge the status quo. 5) Fostering leaders that do not punish mistakes, but rather encourage a culture of experimentation and learning.

Principle 2: Scalability

The CSR literature is liberally sprinkled with charming case studies of truly responsible and sustainable projects and a few pioneering companies. The problem is that so few of them ever go to scale. It is almost as if, once the sound-bites and PR-plaudits have been achieved, no further action is required. They become shining pilot projects and best practice examples, tarnished only by the fact that they are endlessly repeated on the CSR conference circuits of the world, without any vision for how they might transform the core business of their progenitors.

The sustainability problems we face, be they climate change or poverty, are at such a massive scale, and are so urgent, that any CSR solutions that cannot match that scale and urgency are red herrings at best and evil diversions at worst. How long have we been tinkering away with ethical consumerism (organic, fairtrade and the like), with hardly any impact on the world’s major corporations or supply chains? And yet, when Wal-Mart’s former CEO, Lee Scott, had his post-Katrina Damascus experience and decided that all cotton will be organic and all fish MSC-certified, then we started seeing CSR 2.0-type scalability.

Scalability not limited to the retail sector. In financial services, there have always been charitable loans for the world’s poor and destitute. But when Muhammad Yunus, in the aftermath of a devastating famine in Bangladesh, set up the Grameen Bank and it went from one $74 loan in 1974 to a $2.5 billion enterprise, spawning more than 3,000 similar microcredit institutions in 50 countries reaching over 133 million clients, that is a lesson in scalability. Or contrast Toyota’s laudable but premium-priced hybrid Prius for the rich and eco-conscious with Tata’s $2,500 Nano, a cheap and eco-friendly car for the masses. The one is an incremental solution with long term potential; the other is scalable solution with immediate impact.

Practical steps to increase scalability include: 1) Embracing sustainable or ethical choice editing product line by product line, as Sainsbury's has done, beginning with fairtrade bananas. 2) Having a programme of best-practice transfer within the organisation, where small, successful sustainability solutions can be replicated more widely. 3) Collaborating within sectors to raise the standards within an industry, such as the detoxification programme among textiles companies. 4) Participating in cross-sector knowledge sharing forums in order to spread successful practices to other industries, such as the Water Footprint Network and WBCD's Greenhouse Gas Protocol. 5) Working with supply chains, as Walmart is doing with its Sustainability Index, and with customers, as Unilever is doing with its Sustainable Living Plan, and with with bottom of the pyramid markets, as Ashoka is doing with its Hybrid Value Chain model - to encourage behaviour change en masse.

Principle 3: Responsiveness

Business has a long track-record of responsiveness to community needs – witness generations of philanthropy and heart-warming generosity following disasters like 9/11 or the Sichuan Earthquake. But this is responsiveness on their own terms, responsiveness when giving is easy and cheque-writing does nothing to upset their commercial applecart. The severity of the global problems we face demands that companies go much further. CSR 2.0 requires uncomfortable, transformative responsiveness, which questions whether the industry or the business model itself is part of the solution or part of the problem.

When it became clear that climate change posed a serious challenge to the sustainability of the fossil fuel industry, all the major oil companies formed the Global Climate Coalition, a lobby group explicitly designed to discredit and deny the science of climate change and undermine the main international policy response, the Kyoto Protocol. In typical CSR 1.0 style, these same companies were simultaneously making hollow claims about their CSR credentials. By contrast, the Prince of Wales’s Corporate Leaders Group on Climate Change has, since 2005, been lobbying for bolder UK, EU and international legislation on climate change, accepting that carbon emission reductions of between 50-85% will be needed by 2050.

CSR 2.0 responsiveness also means greater transparency, not only through reporting mechanisms like the Global Reporting Initiative and Carbon Disclosure Project, but also by sharing critical intellectual resources. The Eco-Patent Commons, set up by WBCSD to make technology patents available, without royalty, to help reduce waste, pollution, global warming and energy demands, is one such step in the right direction. Another is the donor exchange platforms that have begun to proliferate, allowing individual and corporate donors to connect directly with beneficiaries via the web, thereby tapping ‘the long tail of CSR’.

Practical steps to increase responsiveness include: 1) Adopting Impact Investing principles that assess the effectiveness of philanthropic and community developing expeditures. 2) Institutionalising a variety of stakeholder panels to give honest feedback the organisation's sustainability performance. 3) Engaging in positive, constructive policy lobbying on strategic social and environmental issues, as Seventh Generation has done on product labelling for household cleaning products. 4) Embracing Web 2.0 approaches such as social media and crowdsourcing to improve transparency, as sites like JustMeans have facilitated. 5) Actively working to advance integrated reporting and full-cost accounting, as Puma has done with its Environmental Profit & Loss account, and ContextReporting.org is doing with its benchmarking platform.

Principle 4: Glocality

The term glocalization comes from the Japanese word dochakuka, which simply means global localization. Originally referring to a way of adapting farming techniques to local conditions, dochakuka evolved into a marketing strategy when Japanese businessmen adopted it in the 1980s. It was subsequently introduced and popularised in the West in the 1990s by Manfred Lange, Roland Robertson, Keith Hampton, Barry Wellman and Zygmunt Bauman. In a CSR context, the idea of ‘think global, act local’ recognises that most CSR issues manifest as dilemmas, rather than easy choices. In a complex, interconnected CSR 2.0 world, companies (and their critics) will have to become far more sophisticated in understanding local contexts and finding the appropriate local solutions they demand, without forsaking universal principles.

For example, a few years ago, BHP Billiton was vexed by their relatively poor performance on the (then) Business in the Environment (BiE) Index, run by UK charity Business in the Community. Further analysis showed that the company had been marked down for their high energy use and relative energy inefficiency. Fair enough. Or was it? Most of BHP Billiton’s operations were, at that time, based in southern Africa, home to some of the world’s cheapest electricity. No wonder this was not a high priority. What was a priority, however, was controlling malaria in the community, where they had made a huge positive impact. But the BiE Index didn’t have any rating questions on malaria, so this was ignored. Instead, it demonstrated a typical, Western-driven, one-size-fits-all CSR 1.0 approach.

Carroll’s CSR pyramid has already been mentioned. But in a sugar farming co-operative in Guatemala, they have their own CSR pyramid – economic responsibility is still the platform, but rather than legal, ethical and philanthropic dimensions, their pyramid includes responsibility to the family (of employees), the community and policy engagement. Clearly, both Carroll’s pyramid and the Guatemala pyramid are helpful in their own appropriate context. Hence, CSR 2.0 replaces ‘either/or’ with ‘both/and’ thinking. Both SA 8000 and the Chinese national labour standard have their role to play. Both premium branded and cheap generic drugs have a place in the solution to global health issues. CSR 2.0 is a search for the Chinese concept of a harmonious society, which implies a dynamic yet productive tension of opposites – a Tai Chi of CSR, balancing yin and yang.

Practical steps to increase glocality include: 1. Publicly committing to follow with global best practice principles and standards, such as the UN Global Compact or ISO 26000. 2. Ensuring that community groups and local civil society organisations are consulted in all major developments that affect them, for example using Environmental and Social Impact Assessments. 3) Entering into Global MOU agreements with communities to agree performance targets, as Chevron and Shell do in Nigeria. 4) Having an active employee secondment and volunteer programme, which allows cross-cultural and cross-national knowledge transfer with the organisation and greater sensitivity to local challenges. 5) Developing clear policy guidelines and procedures on how values translate into practice, as Anglo American does for example on issues surrounding bribery and corruption.

Principle 5: Circularity

The reason CSR 1.0 has failed is not through lack of good intent, nor even through lack of effort. The old CSR has failed because our global economic system is based on a fundamentally flawed design. For all the miraculous energy unleashed by Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ of the free market, our modern capitalist system is faulty at its very core. Simply put, it is conceived as an abstract system without limits. As far back as the 1960s, pioneering economist, Kenneth Boulding, called this a ‘cowboy economy’, where endless frontiers imply no limits on resource consumption or waste disposal. By contrast, he argued, we need to design a ‘spaceship economy’, where there is no ‘away’; everything is engineered to constantly recycle.

In the 1990s, in The Ecology of Commerce, Paul Hawken translated these ideas into three basic rules for sustainability: waste equals food; nature runs off current solar income; and nature depends on diversity. He also proposed replacing our product-sales economy with a service-lease model, famously using the example of Interface ‘Evergreen’ carpets that are leased and constantly replaced and recycled. William McDonough and Michael Braungart have extended this thinking in their Cradle to Cradle industrial model. Cradle to cradle is not only about closing the loop on production, but about designing for ‘good’, rather than the CSR 1.0 modus operandi of ‘less bad’.

Hence, CSR 2.0 circularity would, according to cradle-to-cradle aspirations, create buildings that, like trees, produce more energy than they consume and purify their own waste water; or factories that produce drinking water as effluent; or products that decompose and become food and nutrients; or materials that can feed into industrial cycles as high quality raw materials for new products. Circularity needn’t only apply to the environment. Business should be constantly feeding and replenishing its social and human capital, not only through education and training, but also by nourishing community and employee wellbeing. CSR 2.0 raises the importance of meaning in work and life to equal status alongside ecological integrity and financial viability.

Practical steps to increase circularity include: 1) Conducting life-cycle impact assessments on all products and services to understand their cradle-to-cradle impacts. 2) Embracing product footprinting and labelling techniques, such as Tesco has done with carbon labelling and Patagonia has done with its Footprint Chronicles. 3) Providing, or partnering to provide, product takeback, recycling and upcycling schemes, such as Fonebak does with mobile phones and FujiXerox does with printers. 4) Publicly committing to BHAGS (big hairy audacious goals) - what Interface calls Mission Zero, the sportswear industry calls the Race to Zero and John Elkington calls the Zeronaut Revolution. 5) Working to create industrial ecology parks, where waste output from process is designed to be resource inputs into other processes, as is the case with the town Kalundborg in Denmark.

Revolutions involve transition. What markers can we expect to see on the transformational road? The table below summarizes the shifts in the defining features between CSR 1.0 and CSR 2.0.

Table 1: Shifting CSR Features

Paternalistic relationships, based on philanthropy, between companies and the community, give way to more equal partnerships. Defensive, minimalist responses to social and environmental issues are replaced with proactive strategies and investment in growing responsibility markets, such as clean technology. As reputation-conscious public-relations approaches to CSR lose credibility, companies are judged on actual social, environmental and ethical performance (are things getting better on the ground in absolute, cumulative terms?).

How might these shifting features manifest as CSR practices? The table below summarizes key changes in the way in which CSR will be visibly operationalised.

Table 2: Shifting CSR Practices

1) CSR will no longer be limited to luxury products and services (as with current green and fair-trade options). Instead, it will grow to encompass affordable solutions for those who most need quality of life improvements. For example, the way Nestle has fortified their Popularly Positioned Products (PPPs) like the Maggie range, and Danone has fortified their yoghurts in partnership with the Grameen Group.

2) Investment in social enterprises that are self-sustaining will be favoured over cheque-book charity. For example, there are 235 organisations from 58 countries that now support the World Toilet Organization. One of them, Index Award (the world’s biggest design award body) helped to design a SaniShop franchise to brand and design flat-pack sanitation products for scaling-up distribution in the developing world.

3) CSR indexes (that currently rank a limited set of large corporations) will make way for CSR rating systems that translate social, environmental, ethical and economic performance into corporate scores (similar to credit ratings) which can be employed by analysts and others in their decision making. Hence the Global 100 "Most Sustainable Corporations in the World" ranking is much less useful for investors than MSCI's ESG ratings, based on analysts reviewing more than 500 data points and score more than 100 indicators, to score companies on a nine-point scale from AAA to C.

4) Reliance on CSR departments will diminish, as responsibility and sustainability performance is incorporated into organizational appraisal and market incentive systems. This is one of 10 steps to embed sustainability within an organisation of The Prince’s Accounting for Sustainability Project (A4S). For example, the Argentine confectionary company, Arcor, includes sustainability in the performance appraisals of all of their top management, and Xcel Energy links bonuses to carbon reduction and safety performance.

5) CSR 2.0 companies will ‘choice-edit,’ (i.e. cease to offer ‘less ethical’ products), thus allowing guilt-free shopping. For example, British retailer Iceland adopted a policy of GMO-free for all its food products, while The Body Shop has a "no animal testing" policy for all of its cosmetics products. Other examples include Unilever, McDonald's and Nestle, as well as the country of Belgium, which have all committed to sourcing only Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) certified palm oil by 2015.

6) Post-use liability for products will become obsolete, as the service-lease and take-back economy becomes mainstream. Interface was one of the pioneers when it offered its Evergreen Lease carpets, so that all maintenance and recycling was the company's responsibility. A more recent example is Zipcar, the world's largest car sharing and car club service, which provides an alternative to traditional car rental and car ownership. In the electronics industry, Cisco and others have Takeback and Recycle schemes to close the loop on production.

7) Web 2.0 connected social networks that facilitate ‘crowdsourcing’ will replace periodic meetings of cumbersome stakeholder panels. For example, General Electric (G.E.) used OpenEyeWorld's sustainability expert crowdsourcing platform to get critical feedback on its Corporate Citizenship report before it was finalised and published. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has used the open source wiki principle to create its Patent Pool for tropic diseases. Wikirate allows stakeholders to publicly and dynamically update their views on organisations' sustainability performance.

8) CSR 1.0 management systems standards such as ISO 14001 will be replaced with new performance standards, such as those emerging in climate change that set absolute limits and thresholds. The problem with process standards is that organisations set their own voluntary (and often unambitious) targets, irrespective of the scale and urgency of the challenge. By contrast, standards like SA 8000 (a labour standard) and "carbon neutral" or "water neutral" or "zero waste" set quantified minumum performance requirements.

CSR 2.0: The New DNA of Business

All of these visions of the future imply such a radical shift from the current model of CSR that they beg the question: do we need a new model of CSR? Carroll’s enduring CSR Pyramid, with its Western cultural assumptions, static design and wholesale omission of environmental issues is no longer fit for purpose. Even the emphasis on ‘social’ in corporate social responsibility implies a rather limited view of the agenda. So what might a new model look like?

The CSR 2.0 model proposes that we keep the acronym, but rebalance the scales. CSR comes to stand for ‘Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility’. This change acknowledges that ‘sustainability’ (with roots in the environmental movement) and ‘responsibility’ (with roots in the social activist movement) are the two main games in town. A cursory look at companies’ non-financial reports will rapidly confirm this – they are mostly either corporate sustainability or corporate responsibility reports.

CSR 2.0 also proposes a new interpretation of the terms. Like two intertwined strands of DNA, sustainability and responsibility can be thought of as different, yet complementary elements of CSR. Hence, as illustrated in Figure 1, sustainability should be seen as a destination - the challenges, vision, strategy and goals that we are aiming for – while responsibility is about the journey – solutions, responses, management and action that show how we get there.

Figure 2: Corporate Sustainability & Responsibility (The New CSR)

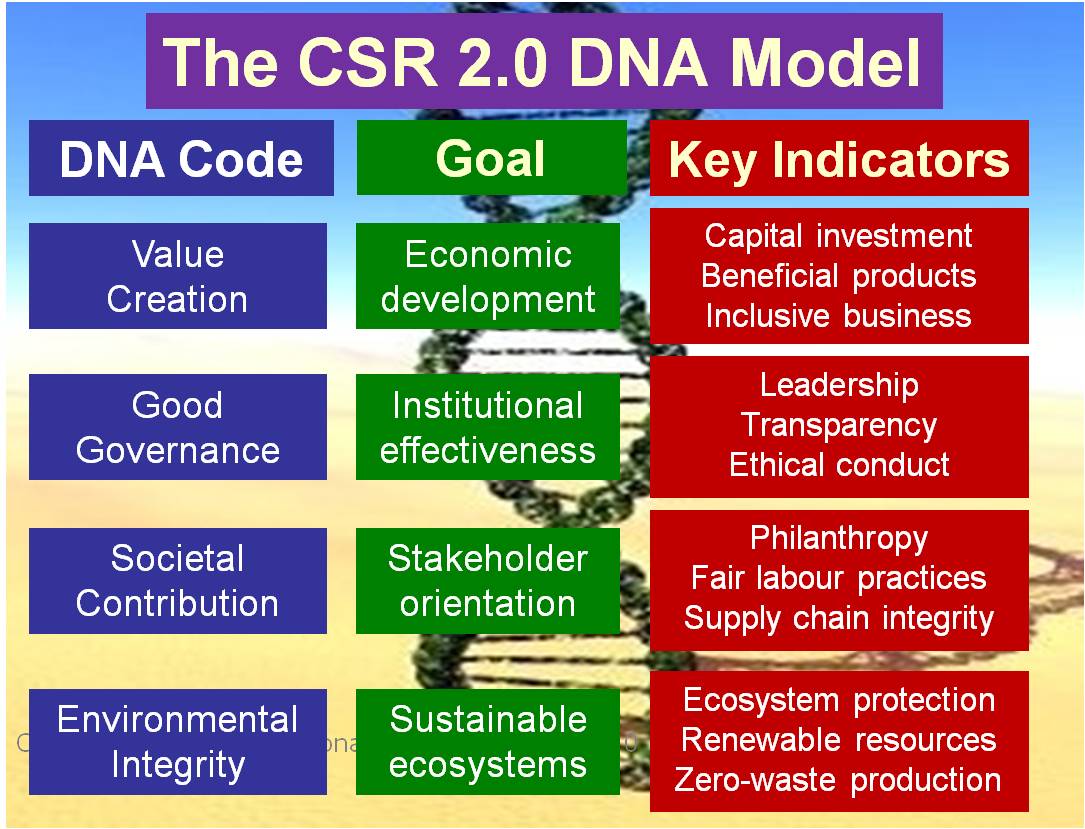

The DNA of CSR 2.0 (Figure 3) represents a new holistic model of CSR. The essence of the CSR 2.0 DNA model are the four DNA Responsibility Bases, which are like the four nitrogenous bases of biological DNA (adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine), sometimes abbreviated to the four-letters GCTA (which was the inspiration for the 1997 science fiction film GATTACA). In the case of CSR 2.0, the DNA Responsibility Bases are Value creation, Good governance, Societal contribution and Environmental integrity.

Figure 3: The DNA of CSR 2.0 (Double-Helix Model)

Hence, if we look at Value Creation, it is clear we are talking about more than financial profitability. The goal is economic development, which means not only contributing to the enrichment of shareholders and executives, but improving the economic context in which a company operates, including investing in infrastructure, creating jobs, providing skills development and so on. There can be any number of KPIs, but I want to highlight two that I believe are essential: beneficial products and inclusive business. Does the company’s products and services really improve our quality of life, or do they cause harm or add to the low-quality junk of what Charles Handy calls the ‘chindogu society’. And how are the economic benefits shared? Does wealth trickle up or down; are employees, SMEs in the supply chain and poor communities genuinely empowered?

Good Governance is another area that is not new, but in my view has failed to be properly recognised or integrated in CSR circles. The goal of institutional effectiveness is as important as more lofty social and environmental ideals. After all, if the institution fails, or is not transparent and fair, this undermines everything else that CSR is trying to accomplish. Trends in reporting, but also other forms of transparency like social media and brand- or product-linked public databases of CSR performance, will be increasingly important indicators of success, alongside embedding ethical conduct in the culture of companies. Tools like Goodguide, KPMG’s Integrity Thermometer and Covalence’s EthicalQuote ranking will become more prevalent.

Societal Contribution is an area that CSR is traditionally more used to addressing, with its goal of stakeholder orientation. This gives philanthropy its rightful place in CSR – as one tile in a larger mosaic – while also providing a spotlight for the importance of fair labour practices. It is simply unacceptable that there are more people in slavery today than there were before it was officially abolished in the 1800s, just as regular exposures of high-brand companies for the use of child-labour are despicable. This area of stakeholder engagement, community participation and supply chain integrity remains one of the most vexing and critical elements of CSR.

Finally, Environmental Integrity sets the bar way higher than minimising damage and rather aims at maintaining and improving ecosystem sustainability. The KPIs give some sense of the ambition required here – 100% renewable energy and zero waste. We cannot continue the same practices that have, according to WWF’s Living Planet Index, caused us to lose a third of the biodiversity on the planet since they began monitoring 1970. Nor can we continue to gamble with prospect of dangerous – and perhaps catastrophic and irreversible – climate change.

CSR 2.0 is, at its core, clarification and reorientation of the purpose of business. It is a misnomer to believe that the purpose of business is to be profitable, or to serve shareholders. These are simply means to an end. Ultimately, the purpose of business is to serve society, through the provision of safe, high quality products and services that enhance our wellbeing, without the erosion of our ecological and community life-support systems. The essence of CSR 2.0 is positive contribution to society – not as a marginal afterthought, but as a way of business.

To take the first steps, we must understand how to overcome resistence to change. According to Richard Beckhard and David Gleicher’s Formula for Change, D x V x F > R, where:

D = Dissatisfaction with how things are now;

V = Vision of what is possible;

F = First concrete steps that can be taken towards the vision; and

R = Resistance to change

In terms of CSR and sustainability, the weakest variable is D, i.e. dissatisfaction with the status quo. This requires connecting people to the impacts of their actions, using tools like footprinting (for ecological, carbon and water), life-cycle assessment and supply chain auditing.

The evolution from CSR 1.0 to CSR 2.0 will be a long and bloody battle. In my own experience, as a South African, it took over 40 years of sustained and organised protest to change the entrenched power of the apartheid government, especially given the powerful vested interests of big companies. The Occupy movement is one important indicator that the element (D) is changing, in a way that is favorable for CSR 2.0, and ought to be encouraged and sustained.

In terms of First Steps, I recommend five actions to organisations that genuinely want to move from CSR 1.0 to CSR 2.0:

1) Re-assess: This is about taking stock of the social, environmental and ethical impacts of company, i.e. creating a sustainability and responsibility performance baseline. Sustainability guidelines by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) and the International Financial Corporation's (IFC) are a good place to start, although ultimately this should embrace life cycle impact assessment (which resulted in BASF switching to recyclable Nylon 6), and full cost accounting (used at companies like Ontario Hydro and Baxter International).

2) Re-align: This is about rethinking what cross-sector partnerships will shift perceptions and practices. In line with the 8th Millennium Development Goal (MDG), organisations need to find partners in business, government and civil society that will complement internal capabilities, while challenging the status quo. Examples include Rio Tinto partnering with the World Conservation Union (IUCN) to address biodiversity impacts and Unilever partnering with UNICEF, Oxfam, PSI, Save the Children and the World Food Programme to help improve the lives of more than a billion people worldwide.

3) Re-define: This is about bold leadership, in particular setting a vision and strategic goals for the organisation, which will inspire and challenge all stakeholders. Examples include former CEO of Walmart, Lee Scott, setting three sustainability goals for the company, including 100% renewable energy, zero waste and making all products sustainable. Interface's Mission Zero set by Ray Anderson, Unilever's Sustainable Living Plan set by Paul Polman and STMicroelectronics Carbon Neutral strategy set by Pasquale Pistorio are other cases in point.

4) Re-design: This is about innovation, especially redesigning products and services to have minimal negative impact. Some companies are taking inspiration from Janine Benyus's concept of biomimicry (learning from nature's designs), such as Interface's "gekko foot" non-glue adhesive tiles, while others are challenged by C.K. Prahalad and Stuart Hart's concept of bottom of the pyramid (serving the poor), such as BP's Oorja low-smoke stove, or Vodafone's MPESA financial texting service.

5) Re-structure: This is about transformation of the context in which organisations operate, i.e. changing the rules of the game, especially the policy environment. For example, supporting bold climate change policies to ensure a carbon price and efficient carbon trading, as the CEOs of the EU Corporate Leaders Group on Climate Change have done. Or working on ingredient labels and salt, fat and sugar level disclosures for food manufacturers and retailers, or product takeback schemes in the electronics industry.

At the heart of the transformational nature of CSR 2.0 is the need to embrace long term capitalism. This means testing all economic activity against five principles of Responsible Capitalism:

1) Investment - ensuring that money is channelled towards productive investments and not into speculative trading in the casino economy, as the Co-operative Bank has demonstrated successfully.

2) Long termism - understanding that real wealth is created by taking a long term perspective, including the needs of future generations, as Generation Investment and Warren Buffet's Berkshire Hathaway practice.

3) Transparency - embracing transparency in revenues, in line with the Global Reporting Initiative, Carbon Disclosure Project and Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

4) Full cost accounting - internalising social and environmental costs (externalities), either through taxes (e.g. on carbon and pollution) and social and environmental profit & loss accounts (e.g. Puma)

5) Inclusion - enacting Michael Porter's concept of creating shared value, and serving the bottom of the pyramid (BOP) markets, as demonstrated by the BOP 2.0 Protocol.

We live in exciting times—a true period of bifurcation. We live on the cusp of the post-industrial revolution, and for the first time, we can finally glimpse what a new model of sustainable business and purpose-inspired capitalism could look like. As with so many things in life, the quest for a sustainable future is like a wheelbarrow. The only way we will make progress is if we pick it up and push forward. And the only way we will motivate people to join us in this effort is if they believe in what we are building. And what are we building? We are building nothing less than a new form of capitalism - one that serves society and sustains the planet.

Many of these identified problems with "CSR 1.0" are directly affected by the large problem I discussed in a longer comment regarding the proposal to improve GRI. [ http://www.managementexchange.com/hack/fixing-corporate-sustainability-r... ]

The problem is that counting up traceable impacts of businesses completely fails as a physical measure. We used the best available method of tracing the energy uses paid for from business revenues for a wind farm, and proved they only accounted for 80% of the total. "Systems energy Assessment (SEA)" [ http://synapse9.com/SEA ]

…That said, including the two "benefit corporation" models in the running as well, this proposal could be changed to define business compliance in such a way to assure that the economy as a whole would remain profitable at its limits of growth. At present, were the physical economy to stop generating growing returns, the financial investment economy would continue to demand them, till the whole became unprofitable.

My proposal applies that performance requirement, where I think it belongs, to investment managers in : " Adopt natural system principles to keep economies profitable at their limits" http://www.managementexchange.com/hack/adopt-natural-system

- Log in to post comments

You need to register in order to submit a comment.