Story:

Designing open collaboration in Red Hat Global Support Services

Sounds like a simple concept – obviously it’s more efficient to let everyone know what questions are being asked and get people to collaborate. Yet most support organizations don’t do it this way. When you make a technical support call, most likely the person who takes your case will spend a lot of time working on it – even if they don’t know the answer – before they eventually hand the question to a more specialized engineer. The person who knows the answer might be two cubes down or halfway across the world, but that person won’t know about your question until somebody else escalates it to her.

This is the story of how we changed the way we solve customer problems in Red Hat Global Support Services from the traditional “escalation model” to a new collaborative model based on a concept we call “intelligent swarming”. Since we couldn’t find anyone who had done this before, and there was no script to follow, this is also the story of how we used open collaboration and design thinking to develop the process itself.

Red Hat's Global Support Services (GSS) organization is accountable for customer loyalty. In that capacity, we're in the business of solving complex technical problems experienced by our customers. Our technical support engineers, technical account managers, and software maintenance engineers work from 16 countries throughout the world, providing 24/7 service in nine languages. We support a wide variety of enterprise software solutions, from our flagship Red Hat Enterprise Linux, to our JBoss Enterprise Middleware Stack, Red Hat Enterprise Virtualization and newer Cloud Solutions. Many of the questions we receive from customers are consultative in nature. That is, beyond helping customers with straightforward questions about our products, we advise customers on intricate technical architectures, and help them solve complex problems. To that end, it is critical that we effectively leverage the knowledge of our talented staff of Red Hat certified technical associates in a scalable fashion.

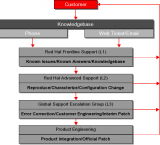

Until we implemented the changes described in this story, Red Hat used a traditional tiered support model. A level 1 associate would work on a case until they could no longer make progress, and then escalate to level 2. Level 2 would do the same, and escalate to level 3 as needed. Each escalation had some overhead of an escalation process, and each involved assigning the issue to a specific engineer who was more senior than the previous one (this was a manual process). Each engineer was only aware of the questions they personally had been assigned. Just like the 25 questions circulating through the room of 100 people.

While this escalation model has served most of the support industry well for many years, it has some drawbacks:

-

Support cases may take more time than necessary to reach the right resource. Think of those 25 questions in the room filled with a 100 people – how long does it take for the question to find the person who knows the answer?

-

Individuals are motivated personal metrics of success – how many issues can they close in a week? This can lead to behaviors that might not be productive. For example, associates closing cases prematurely to improve their numbers, or associates not helping each other for fear of their own numbers slipping as a result.

-

The culture that forms in this model is one of knowledge hording. People see that the more senior engineers have very specialized knowledge, and that gives them personal respect as well as positional power. The more power their knowledge gives them, the less incentive they have to share. This contributes to cultural barriers forming between the different groups.

The old model:

With Red Hat's rapid growth year after year, we knew we couldn't continue to simply add technical support staff linear to revenue increase. In order to scale effectively, we had to innovate around how our associates worked. So, in February of 2009 the management team of Red Hat GSS began a journey to determine if we could serve our customers better, and ultimately increase customer loyalty, by improving the ability of our highly trained, globally diverse technical support associates to collaborate with each other. The goal for our collaboration project: get the right people looking at the right issues faster, so that customer problems are resolved more quickly.

The fundamental idea was that if we could take away certain structural, cultural and procedural barriers that separated different groups of associates, we could increase the flow of knowledge, reduce the duplication of efforts, and ultimately provide customers with more accurate, more consistent, and faster results.

In addition, we wanted to design a system where the goals (both individual and organizational) were based on outcomes rather than activities. More on this in the “Benefits and Metrics” section below.

During the 18-month period of developing this new program, there were a few key innovations both in the process design as well as the design of the new workflow of our associates. These are described in detail under “Challenges and Solutions”.

-

Process design (how we developed the new workflow)

-

Use open source development principles in the process design (do it transparently, allow anyone to contribute ideas, try things out quickly and fix them as you go).

-

Doers as designers: make managers advisers and recruit a team of individual contributors to design the actual program

-

Global participation: ensure design team has the perspectives of every team in every region

-

Use elements of design thinking. Specifically: define the problem from the perspective of the doers, think about root causes of the problem, brainstorm possible solutions, and rapidly prototype different solutions until the right one is found (gathering and discussing feedback as we go).

-

-

The new workflow for our support associates (what we actually designed)

-

Base the workflow on principles of community and transparency true to our open source principles

-

Understand that we're not merely talking about a change in workflow, we're talking about a culture shift away from individuals striving for personal indicators of success to everyone working toward team indicators of success.

-

It is important to define collaboration and socialize internally what it means in our context and why it will make us both as an organization and as individuals more successful

-

Deciding to increase collaboration is one thing, but actually enabling increased collaboration and then fostering its use by associates is no easy task. While our associates have always freely collaborated within small groups (people who sit near each other, for example, or people who work on a similar technology), our vision was to take advantage of our organization's collective knowledge by fostering collaboration on a global scale. That meant connecting people from several different functional roles, across 16 countries, through nine languages, and dozens of areas of domain knowledge, who had traditionally used separate, disconnected knowledge and case management systems.

Finding the right design process

Figuring out how to design a workflow that could accommodate this ambitious goal proved quite difficult. We assembled a project team and went through several iterations without feeling like we had something solid enough to fully implement. We started with a few pilot groups collaborating on a small scale, but found logistical as well as fundamental attitudinal problems stymied the open collaboration we envisioned. While we had successfully articulated the goals of our efforts, we were not making progress on a solution.

Then, after several months of false starts, we finally had a breakthrough. What if we got rid of the project team, which consisted mostly of managers from different areas of the organization, and instead asked the associates themselves to get together and figure out the best way to achieve the goals? This would, after all, be consistent with open source principles – enable people to work together to develop a solution that makes their lives easier.

The existing project team became what we called the “core team”. This team consisted only of managers, and their role would change from actually designing the solution to being more of an advisory board for the project. We then solicited volunteers for a new team, which we called the “design team”. This team was composed of about 15 technical associates; a representative from every region, every team, and every skill level. These associates were all enthusiastic and energized by the project – but that didn't mean they all thought it was a good idea or agreed on how to implement it.

My role was to facilitate the design team meetings (using design thinking techniques), make sure the conversation remained productive and on track, and to make sure all voices were heard.

The design process wasn’t easy. We alternated meetings between early morning and late evening to accommodate various time zones. Some associates were joining our calls at 5:00 AM, 2:00 AM, 11:00 PM or other odd hours in their local timezone. Emotions ran strong; some of the discussions questioned the validity of certain roles and opened the door of possibility to major change. People feared of losing their relevance, of sacrificing their exclusive status as experts of a particular topic, of having to take on more work than they previously had, of having to spend more time discussing problems with team members instead of just doing the work themselves. The implicit understanding that many people in technical fields have is that knowledge is power. Doesn't increasing collaboration and knowledge sharing mean that you give up that power?

The Solution: A new collaborative workflow

The design process taught us that breaking down silos and improving collaboration would be a major culture change and require a comprehensive change management effort that could potentially take years to be fully realized. Far beyond the scope of the original vision, we spent the next twelve months designing and revising what would become the new workflow for all our technical associates worldwide, along with new unified knowledge and case management systems, based on what I now refer to as “intelligent swarming”. Along the way the design team worked through dozens of questions, tough conversations, heated debates and disagreements.

For example, one key realization that we came to was that not everybody had the same understanding of what it meant to “collaborate”. Does it mean that you work on a problem until you reach the end of your ability, and then ask somebody else to work on the problem? Or, does it mean you work on the problem and ask for help as you need it, but maintain ownership of the case until it closes? Or, should we strive for people to proactively contribute to cases where they can help, based on monitoring cases appropriate to their skills, regardless of of whether they are asked to help? The answer would entail very different workflow guidelines.

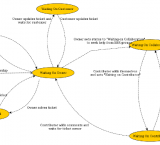

During one design session early on, I asked everyone on the team to each draw a picture of how they thought the workflow should look in an effort to move the conversation forward. Many different diagrams were shared, several of which kept the principles from the existing escalation model, but renamed the terms. That is, people still envisioned putting a case through some kind of process by which a more senior person was tapped to help, but instead of calling it “escalation” they called it “collaboration”. This was revealing, and became a theme. Understanding the concept of collaboration at an intellectual level is one thing, but actually internalizing it quite another.

Then one diagram came in from a frontline support associate in Beijing that looked truly original:

Rather than envisioning a traditional phased workflow, this associate wanted to visualize the different states a solution could be in during its life cycle based on the concepts we had been discussing. This workflow diagram has been updated and tweaked several times since it was first created, but it largely resembles the original and has served as a simple but effective guidepost for the project. Some elements of the workflow are similar to the old one – for example a frontline (junior) associate is the “first touch” on a new case and the first thing they do is search the knowledge base to see if they are dealing with a known problem or a truly “new” problem. If the case owner can solve the case on their own, they do so. There is no reason to collaborate for the sake of collaboration. Any issue that has been solved previously should be found in the knowledgebase, leaving only previously unsolved problems to the collaborative workflow.

If, however, the case owner needs help, they do not hand the issue off to someone else. Instead, they signify they need help by changing the status of the case to “waiting on collaboration”. This is where the new model really kicks in. All associates belong to different technical “domains” that focus on different topic areas. Associates of all skill levels view all the cases in the system through a filter for their domains. They review cases relevant to their skills, and can help guide each other toward resolution. More junior associates take more cases up front, while more senior associates spend more time contributing to cases owned by other people through the new collaboration model. Thus senior associates see more issues than they did before, which means their expertise is accessed more quickly, junior associates are sticking with cases longer, learning directly from the senior associates rather than simply handing issues off. Customers, ultimately, are getting the answers to their questions faster.

The workflow effectively solves its primary goal: get the “right” people working on the “right” cases faster, so that customer problems are resolved more quickly. The workflow has several additional benefits:

-

Knowledge sharing: associates who have less knowledge in any given area learn directly from the senior associates. At the same time senior associates are recognized for sharing their knowledge rather than hording it.

-

Removing barriers: the divisions that separated the tiers of support blur as people collaborate more, resulting in a broader sense of “team” and aligning everyone around the goal of solving customer problems effectively and efficiently

-

Cross-geo collaboration. We're also seeing a lot more direct collaboration between associates in different parts of the world, further removing barriers between teams that tend to exist from office to office. One global workflow forces discussion and resolution of snags related to how things work in different regions

Early data indicate that the combination of Knowledge Centered Support (a methodology for incorporating knowledge creation and reuse into the workflow of solving customer problems) and our new intelligent swarming model allows us to handle greater call volumes without increasing staff. We also see shorter time to resolution of support cases, which leads to increased customer satisfaction. These efficiency gains are early indicators of a positive ROI and are a direct result of empowering our associates to take the lead in designing their own processes and procedures, the open-source way.

In the coming months our goal is to move from adoption of this new model to proficiency, working out the kinks and refining the metrics that we use to measure success. One thing we we no longer do is make goals around specific activities. An important realization we came to as we changed our workflow was that setting any kind of goal on an activity invariably results in undesired behavior. It's important that we strive for goals that reflect outcomes and also take into account the team success over the individuals success. For example, its tempting to set a goal such as “Each associate will contribute to X number of cases per week”, thinking that this would spur people to collaborate on cases. But, what you might find is that instead of truly collaborating associates simply leave “low value” comments (an activity) on large numbers of cases to meet the goal, without really helping to solve any specific cases. A better goal would be something like “The technical domain the associate is a part of will reduce time to closure on new cases by X percentage points”. The outcome here is that the team actually solves cases, rather than perform a specific activity.

The Big Picture

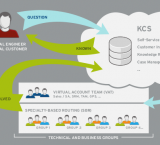

Below is a diagram that shows how swarming (called SBR in this diagram), combined with Knowledge Centered Support (KCS) enables us to leverage collaboration for new cases, while re-using knowledge from previously solved problems to provide answers to customers more quickly. We're also looking at ways to improve our knowledge of the whole customer by better engaging the entire team that interacts with a customer (called the virtual account team in this diagram).

Embarking on this journey ultimately taught us lessons that we didn't expect – not just in how to manage collaboration for our associates' day to day jobs, but in how to use open collaboration as a management team to innovate on process design in our organization. It turns out the answer was right in front of us all along – use the open source development concepts our company was built on.

Our new collaborative workflow is far from perfect. There are still tough questions, problems we encounter, and improvements we recognize we need to make. Over the coming months we will focus on measuring the effectiveness of our new intelligent swarming model and increasing its efficiency. To do this, we'll keep building on the lessons we've learned in developing the program: resist the temptation to apply changes or improvements from the top-down, and let the people who do the work design and improve the process, transparently.

Greg Oxton, of the Consortium for Service Innovation, supplied the analogy of 100 people in a room answering questions on their own vs. via collaboration.

I've had several requests for more detail on the actual workflow that we developed to enable collaboration. I'll be expanding this story with that detail in the coming days.

-Sam

- Log in to post comments

- Log in to post comments

- Log in to post comments

Sam,

Thanks for the story. I have two comments to share:

(1) I appreciate your reminding us that "not everybody has the same understanding of what it means to “collaborate”". The root of the word, of course, refers to co-laboring, i.e. two or more people working toward the same outcome. Unfortunately, according to common usage, the word "collaborate" has been hi-jacked to refer to the sharing of documents and online forums. There is a big difference between talking/sharing and doing. Co-laboring, as you point out, is really about getting something done.

(2) I liked the concepts embedded in the workflow your team developed. For some time now, I've been working on a similar paradigm called commitment-based management which expresses organizations as a network of interrelated requests and commitments to deliver. Co-laboring is explicit. One person (the requester) makes a specific request of someone else (the performer). The performer is obliged to make an explicit response, i.e. agree to deliver on the request, decline, or make a counter-offer. Presenting the performer with the opportunity to negotiate their delivery commitment clarifies ownership and assures accountability, not to mention increases the likelihood that the delivery will be made on time. In the context of your example, the customer makes the initial request of the frontline associate who makes the first commitment to the customer. This first commitment in the chain is "delivered" by either an immediate solution to the customer's problem or a promise to respond back to the customer within some time period (e.g. service level). The frontline associate then makes a secondary request to someone with more expertise (i.e. escalates the problem). The associate is now engaged in two parallel and interrelated "conversations" - they are the performer to the customer and the requester to the second level expert. Taken more broadly, the whole organization can be seen as a network of these conversations around negotiated commitments. The principles are the same whether departments make requests of other departments or whether the CEO makes requests of Vice Presidents.

Commitment based management has been described as the most important new management principle to emerge in the last several decades. These simple, but profound innovations in work management have been profiled in the Harvard Business Review, MIT Sloan Management Review, and the Wall Street Journal. Software technology to facilitate and track these conversations for action is coming which will improve coordination, visibility into execution, and accountability by presenting a clear picture of who will do what by when. These innovations will also disrupt current top-down/command-and-control work norms and increase trust by capturing performance metrics and exposing patterns of behavior. Let me know if you'd like to learn more.

Keep up the good work!

David

- Log in to post comments

Thanks for your comment! Interesting note on the origin of the word collaborate. One surprising thing I found was that many people don't really understand true collaboration conceptually (which is just a training/teaching/coaching challenge). I would like to learn more about commitment based management. Let me know if you recommend any good links on the topic.

Thanks

Sam

- Log in to post comments

- Log in to post comments

Excellent recap of your experiences. Please continue to share your progress.. Congratulations on your implementation..Definitely proves out a Japanese proverb "None of us are as smart as all of us"

- Log in to post comments

Thanks for great success story Sam. Very helpful and interesting approach on doing support.

- Log in to post comments

You need to register in order to submit a comment.