Hack:

Silo-Busting with Formal Networks

- Unlike matrix structures, formal networks organize work through shared interest and are therefore based on collaboration (vs. authority). They avoid the complexity and ambiguity that some matrices generate by specifying multiple “bosses."

- Unlike informal networks, formal networks have access to real resources (i.e., they submit budgets based on specific innovative plans) and support infrastructure (e.g., network coordinators to facilitate interactions among members). They also operate with clear objectives. Contributions of network members against these objectives serve to inform individual evaluation processes (to create accountability for the resources invested).

A couple of illustrations of this issue:

- Companies organized by geography (e.g. regions/countries) may have product/functional teams that carry out similar or complementary tasks (e.g., developing new product features, customer training, development and training of product staff). These pockets of expertise can be disconnected because product specialists don’t have the motivation or ability to easily connect with peers in other geographies. This results in regular re-invention of the wheel and missed opportunities to build deeper product expertise (and a broader sense of community within the product “specialty”)

- Many institutions--such as those in regulated or public contexts (e.g., government departments, universities, hospitals)--have rigidly separate departments and roles (e.g., between unionized and non-unionized workers, between doctors and other staff members, between fields of study and specialties within fields). These divisions have de-facto instituted a “creative apartheid,” whereby only specific individuals in the organization are allowed to contribute to specific initiatives (e.g., strategy, product development, resource allocation) development initiatives. This cuts off from the creative process a number of people who might well be able to contribute fresh insights.

These problems are rooted in several “Management 1.0” principles and practices:

- Formal organizational structures typically do not group employees along lines that facilitate knowledge exchange, enthusiasm, or passion for what they do.

- This, coupled with a widespread assumption that tasks need to be assigned (vs. chosen), leads people to ignore and/or discount contributions from unconventional sources.

- Management processes (e.g., resource allocation, talent development, performance review) are typically centered around the work of specific silos and therefore often discourage activity across silos. For instance, performance review systems do not recognize contributions made outside of a person's immediate area of responsibility within his or her unit (sending the implicit message that cross-cutting initiatives are unimportant).

- Affinity bias leads individuals to more highly value the contribution of individuals with backgrounds similar to their own.

- Clear, shared objectives and value proposition

- Dedicated roles, including empowered network “owners” and network coordinators

- Flexible membership and disciplined protocols

- Real resources and connection to the organization’s core management processes

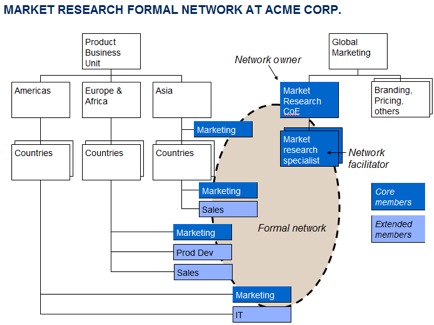

We’ll illustrate each component taking a hypothetical case study--say a formal network focused on “market research” at ACME Corp, a global company organized around geographic lines (see illustration below). In a later section, we suggest baby steps to launch each critical component.

1. Clear and shared objectives

For a formal network to work effectively, its scope needs to be explicitly defined, as informal networks can make overlapping claims on the same activities. These will often take the form of key economic goals and the knowledge needed to accomplish them. Setting a concrete and compelling objective is also critical since it becomes a driver for participation and continued engagement. Given the voluntary nature of much of the work they carry out, formal networks rely on mutual self-interest of their members--put simply, if networks don’t add value to their members, they will wither.

ACME example: The goal of ACME’s market research formal network is twofold: (a) develop core market research capabilities across various geographic markets and (b) aggregate customer insights and distill key findings for internal customers within ACME (e.g., marketing department, product management, customer service). The specific benefits for members are: (a) professional development for marketing professionals interested in a market research track and (b) greater effectiveness on the part of ACME employees that are responsible for generating and leveraging market research data (e.g., to design better products, or more effective customer service).

2. Dedicated roles

To properly function, networks need to have dedicated roles. Two are particularly pivotal: network owners and network facilitators.

- Network owners: Network owners facilitate interactions between members, stimulate the creation of new insights, maintain the network’s collective knowledge, and help members do their jobs more effectively and efficiently. The network owner isn’t a boss but rather a “natural leader.” The owner of a network doesn’t oversee its work or personally manage or evaluate the performance of individual members but may provide input into the evaluation process. The responsibilities of the network owner are primarily limited to its activities, such as organizing the infrastructure supporting it, developing an agenda for maintaining its knowledge domain, build a training program, holding conferences, and qualifying members as professionally competent. Despite this limited hierarchical authority, a network owner should be held accountable for the network’s performance (e.g., the quality of the market research ACME produces, based on the feedback from those who use market research). The network owner is most likely appointed by hierarchical leadership, but he or she needs to have significant credibility with fellow network members to be effective.

- Network facilitators. Formal networks require one or more facilitators to organize meetings and calls, manage best practices, act as liaison to other communities and senior management, and connect members to each other. The facilitator role varies depending on the objectives of the network. Network facilitators would be elected by the members of the network.

ACME example:

- Network owner: The head of ACME’s Market Research Center of Excellence (CoE) at the corporate level leads the network. The center of excellence has a handful of experts working at headquarters, but no reporting relationships to marketing or other resources with each geography. (Note: the network owner needs to be viewed as a legitimate "natural" leader by the members of the network--he or she need not to be a hierarchical leader. See "First Steps" section of this hack for a description of how natural leaders could be identified).

- Network coordinator: The network coordination role (e.g., scheduling meetings, ensuring progress against shared objectives) is taken by a member of the Market Research CoE center for 50% of her time. The role rotates to another member of the network every other year.

3. Flexible membership and disciplined protocols

In addition to finding and defining the roles of network leader and coordinator, most formal networks need to connect to two kinds of populations to succeed: core members of a network, whose formal roles make membership a “must have,” and extended members, whose membership is discretionary (based on their professional interest and in the network’s activities.

ACME example: the Market Research Formal Network has a core group of marketing professionals that report to specific geographic units within the “product” organization. In addition to the core marketing group, the network also includes interested participants from other functions (e.g., product development, sales, IT) who have an interest or specific expertise in market research activities. The network owner can’t give members orders, but can encourage them to work for the network’s benefit (e.g., by asking them to develop new market research techniques or to aggregate findings across geographies).

Formal networks should also have explicit guidance on time commitment and rules of engagement, which help guide how the rest of the organization interacts with members of the network, as well as how members interact from each other.

ACME example: All members of the market research formal network are be expected to participate in the annual conference (1 day/year), as well as to devote 1 hour a week to network-building activities (e.g., pushing a specific knowledge initiative, fielding calls from colleagues seeking market research advice). Rules of engagement for those seeking market research advice from network members could include norms such as: read documents authored by an expert before calling him/her (don’t use expert time to understand basics); consult with the network coordinator to find the most appropriate expert for specific questions.

4. Real resources and connection to the organization’s core management processes.

Each network should have a discrete budget to finance investments, which enable it to offer members added value. These investments might include infrastructure--both human and technological--to support network interactions; codified knowledge in forms such as documents, internal blogs, and “networkpedias;” training for members; and activities such as conferences to build a social community.

Budgets are funded based on the ability of each network to demonstrate value to its members and the organization more broadly. Some performance measures can be quantitative, such as the level of member participation in network events/conferences, knowledge documents produced, the effectiveness of responses to inquiries, and the ability to find appropriate partners for dialogue quickly. However, the real measure of the network’s success would be qualitative assessments, made primarily by members (with input from company leaders), of its effectiveness in realizing its mission. These assessments might come in the form of stories or case studies illustrating improvements in personal productivity.

Beyond being integrated into budgeting/funding processes, networks will require other connections to an organization’s core management processes in order to thrive.

ACME example: The Market Research formal network is supported by talent review and development processes:

- Individual performance reviews explicitly recognize an individual’s contribution to the formal network (e.g., boosting the reputations of people who contribute distinctive knowledge to network members)

- Members of the network have exclusive access to additional professional development opportunities for members (e.g., the ability to attend external conference/training programs in the knowledge domain of the network)

Individual benefits:

- Improve one’s own job performance by learning from and collaborating with others

- Filter interactions and focus on the most productive ones

- Build reputation within and outside the organization

- Create new opportunities for talent

Organizational benefits:

- Better economic results from impact of network’s activities (higher effectiveness and efficiency)

- Better allocation of resources and expertise towards important priorities

- Build more and deeper personal relationships among diverse members of a community that transcends traditional silos--resulting resulting in higher motivation, engagement

- Simpler organizational design, replacing cumbersome and outdated matrix structures

- Inspire, encourage and reward innovation designs that cross over genders, ages, careers, and experiences.

- Identify initial members of the network. These would include market research specialists whose membership is required (the core members), as well as interested practitioners from other functional areas (as identified by core members).

- Framing the near-term priorities and identify the "natural leaders." Poll the initial members of the formal network on the key goals/initiatives for the group in its first 6-12 months, as well as on who they think should act as the inaugural network leaders. For the network's priority, respondents could be asked a 20 word response to the following question: If you led a game-changing initiative to improve ACME market research for significantly better product development and customer satisfaction, what would it be? For identifying natural leaders, the survey could ask respondents to identify in the network who:

-Is sought most often for advice on any particular topic?

- Determine roles and draft initial game plan. Based on the initial responses, a network leader (or, even better, 2 or 3 leaders that have emerged through the process of peer nomination), will be appointed (most likely by the head of the marketing function). The leaders will then recruit network coordinators and will draft up an initial 12-month plan around network priorities and activities (e.g., specific knowledge initiatives, network conferences/meetings) and the measurable targets around these. The plan will also include the protocols for effectively running the network (e.g., weekly calls, quarterly meetings, big annual conference), and the resources required.

- Iterate plan with members, secure corporate support, and begin execution. Network leaders openly share the plan with all members and iterated based on feedback. The revised version is then shared with Marketing function and other corporate leaders for approval (required especially for access to more resources for operations and member "perks" like access to extra professional development) and then executed.

- Assess impact, tweak, and scale. Over the course of the year, the network will progressively discover what specific initiatives and ways of working will be most effective, and adjust plans and protocols accordingly. At the end of the year, all network members should review progress--if the yearlong management "experiment" proved successful, the network should expand its scale and scope, and ACME should seek to create similar networks in other parts of the organization. At this point, the organization will also start making changes to its management processes so that these encorage effective formal networks (e.g., including membership of/impact in a formal network as part of the performance review process).

- Mobilizing Minds, by Lowell Bryan and Claudia Joyce (Michele was involved in the research)

- "Harnessing the Power of Informal Employee Networks," by Lowell Bryan, Leigh Weiss, and Eric Matson

- Communities of Practice, by Etienne Wenger

- Innovation, Design, and the Human Brain, by Elen Weber

It seems to me that you are coming at thin from the middle up. Silos frequently reside at the officer level and are consequently the most difficult to crack. How would your approach help when the silo needing to be breached is at what I ca the "corporate bully" level?

I fear that what you have suggested here will fall into the category "This too shall pass". Isn't attacking the silo problem from the middle like pushing a string up hill?

- Log in to post comments

Thank you for your Hack.

I am all for the better acknowledgement and resourcing of natural networks. But I find myself still feeling unable to get past the challenges you identify with formalizing networks.

I really like Wagman et al's research that finds that CEO’s frequently challenge individuals but don’t challenge the team as a whole to work collaboratively.

http://www.enjoyleading.com/essential-tools/leadership-teams-struggle-–-but-you-can-avoid-common-mistakes/

Until senior managers are together accountable for the whole enterprise (including the wider community) then it isn't good leadership.

I'd be keen to hear more from this team as your ideas progress and you get feedback for how formal networks are embedded in practice.

Thanks, Loretta

- Log in to post comments

I really like the thought and concept behind this hack. I believe though that high performance teams are self-organising. As a result, my quibble (and it is just a quibble) is the use of the term "owner" which is always associated with silo mentalities in organisations. Individual ownership is inconsistent with the concepts you are describing.

I understand why you have used facilitator where you did, and that's probably right. How about a Network Tserpa, the person who is your practical Network Guide?

Nevertheless really good and thought-provoking work.

Cheers, geoff

- Log in to post comments

Recently I facilitated leaders at a large university and was reminded by top administrators there that silos and unnatural barriers to integration impede innovative results far more than we realize. They can also prevent uniquely diverse backgrounds from growing shared talents for new pathways forward. So glad the MIX attempts to look past these and operate differently.

As to your well taken points about facilitation of these teams (without typical barriers that come from any one segment of ownership) -- that’s a far more complicated process to model, you’ll likely agree.

Facilitation and tools such as tone and talent unleashing work brilliantly together - and are central to leadership innovation work I do - which makes me curious to hear more about how you sense high performance that cross silos without individual ownership. Can you elaborate a bit more? Any examples?

What a critical topic – and when it is conquered by the kinds of excellent contributions so fluid here and at the mix – we will have crossed more silos organically toward brilliant innovation on the other side. Thanks Michele and all! Count me in! You?

- Log in to post comments

- Log in to post comments

You need to register in order to submit a comment.